Battle Birds: Re-Dressing the Fighting-Cock, and the Architectures of a non-Human Avatar

Natalie Lis

At a time when the word unprecedented lost its meaning, and while the world grappled with a pandemic, an invitation arrived from the organisers of a symposium to submit an object for discussion. This object was to be “an apparatus of resistance” which might allow for “an extension of thought toward materiality.”[01] During that strange period of covid-induced isolations, material things had been rendered threatening, vectors for new strands of the disease, only safe if doused in sanitisers and disinfectants, or at least left to rest before handling. Spending hours at home in the Sunshine Coast, north of Brisbane, reading and researching from my home office, I found in myself a growing desire to touch, sense, and connect creatively through a physical design exercise. The invitation for the symposium was a call that permitted a form of touch outside of my sanitised isolation, a contact with someone outside my circle. It teetered on the devious and I, of course, submitted a proposal for an object. As per the organisers’ instructions, it should fit in a box, of limited size and weight, and be posted to another symposium participant, who would open and present the object for discussion at an event several weeks later. In response, I constructed an object from my, then, developing intellectual work. The object was quickly prepared, carefully packaged, and sent away via post. And so, a constructed chicken-object made its way across the world, a former bright pink husk, a hybrid chicken-wire frame and wire-frame chicken, intended as a prompt for a conversation. The idea was born out of my research into what I call human-built avian architecture, and it was intended to help me wrap my head around what I saw as a troubling trend in backyard chicken keeping: the rise of mother machines and gladiatorial ghosts. With the increasing popularity of chicken keeping, I saw an expanding range of avian bodies appropriated by human gendered roles, dress and ideologies, often in highly exploitative ways. These relationships are strongly connected to a human-built avian architectural history that has long supported how chickens are kept, and how gender is understood in these settings. The object I made shifted the scale of my intellectual escapades from the large ambiguous mass of chicken, eggs, and chickens to the singular body of an individual rooster.

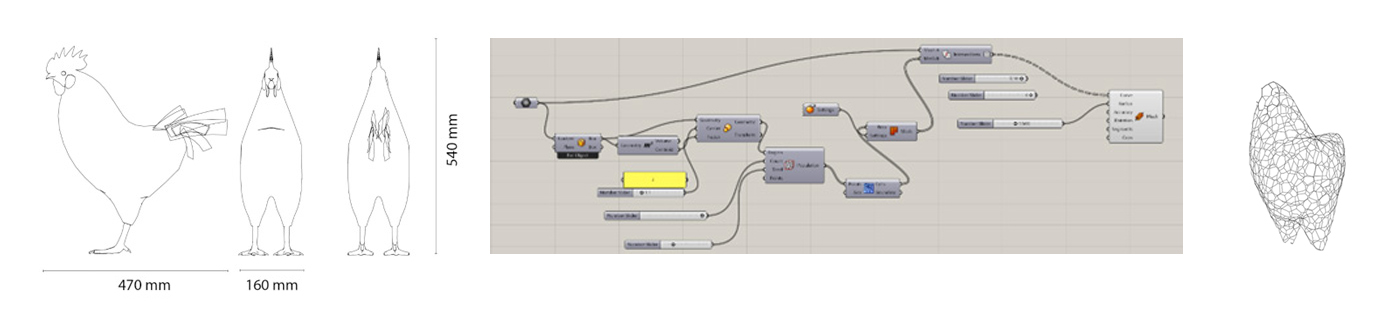

The dimensions of an average male chicken were used to build a mesh in the 3D modelling software, Rhino. The mesh was refined using the parametric software, Grasshopper. A Voronoi script, chosen superficially for the chicken wire pattern it generated, was applied to the mesh. This was re-figured into an approximation of a body, forming both a prosthesis and housing for the new-avian avatar. Physical study models re-presented this digital construction in material terms, in chicken wire originally inspired by wire mannequins of human forms. The pink was initially the only colour the fabrication lab had in excess, which contained no real substantive value, and yet the colour had agency. Engaging with the shell became cumbersome, manipulations felt intrusive, and any exterior intervention was diminished, somehow, by the fleshiness of this incidental pink finish. The re-presentation or transition from weightless digital avatar to pink cellular tissue caused the project to shift, as the mannequin matured into a screen, as the pink was spray painted into a bone-white frame, and as the form was wrapped in white linen.

Writing now, several years later, when the world has returned to more familiar (if no less confusing) patterns and practices, I aim here to re-frame this initial object and its associated images, to continue the ‘extension’ proposed by the symposium organisers, only this time from materiality back to thought, from an object back to a critique. I will offer a selection of images of the initial object, and outworkings of that object, to frame questions which have developed or been brought into focus since, and as a result of, the production of that object. The object was abandoned after the symposium, and is presented here as it was then, but it provoked ideas, reflections and re-conceptualisations that would not exist in my research if I had not gone through its processes.

The images presented throughout this description – initial sketches, quickly produced and offered as openings to thought rather than refined pieces – structure a discussion of a particular figure and its associated architectures: the fighting-cock and the cockfighting pit. Both are shaped by a human-built avian architectural history saturated with masculine gender identities that conflict with prevailing society, despite the same society accepting, or consciously ignoring, other gendered animal uses in farming and agriculture. The fighting cock is represented in literature and paintings as an actor and symbol of masculine valour. A surrogate human or avatar, he displays an animality beyond human social acceptability. He is raised in isolation and conditioned to fight with little provocation. His body is modified through dubbing and cutting to improve his fighting class, no matter if it impairs the victor for the remainder of his life. He rises to combat adorned with dangerous human-crafted weapons, known as gaffs. The cockfighting pit is a similar purpose-built apparatus, an architectural space of action. It connects the prosthesis worn by the cock to the spectators around the ring. By spending time with these two figures, prompted by an invitation to return to the initial object and its drawings, I aim to fashion a re-imaging and re-imagining of the fighting-cock as a tool for critique today.

Weathervanes are some of the rare examples of roosters still present in the built world. Rooster weathervanes have gained some recent attention when the original weathervane of Notre Dame de Paris survived the 2019 fire, being found in the rubble and it is now on display in the cathedral. Its replacement, design by architect Philippe Villeneuve, was affixed to the spire in 2023.

Gendered Spaces: Cockpits, Henhouses and Egg Sheds

Gendered dynamics permeate chicken keeping and how chickens are used in industry and in smaller-scaled domestic settings, such as farmyards or suburban gardens. Although a chicken–human history is not easy to sum up, gendered dualisms prescribed to chickens within human societies can be characterised as tied to either an image of hyperfeminine hens as passive egg laying machines, or roosters as hypermasculine and aggressive. Even lexically the term ‘chicken’ in the English language typically refers to hen.The mother-hen-chicken-motif populates children’s literature and marketing materials despite the fact that the hen has largely been replaced as a mother machine in battery systems and other industrial and small-scale egg production practices. The hen’s body and her byproducts are regularly portrayed in popular media and advertising as something to consume, whereas the sexual re-production of chickens is overlooked. In The Sexual Politics of Meat Carol J. Adams observes a phenomenon in which ‘feminised proteins’ are considered something safe to harvest and eat, and although Adams focuses on mammalian bodies and their byproducts, such as milk, chickens’ eggs are likewise an example of a feminine protein.[02] The passive positioning of eggs, as a victimless protein, in holiday rituals or marketing strategies are good examples of the way feminised proteins are considered unthreatening. Yet, as roosters cannot lay eggs they are exterminated when one day old in industrial egg production,[03] and males are typically banned from small-scale suburban chickens keeping settings, in part because they are considered nonproductive, and their vocalisations may be considered a nuisance. Despite this, all chickens raised for meat or for egg production are hatched from a sexually fertilised egg. Somewhere between the egg machine and the plastic wrapped grocery store product is a sperm machine.

Roosters are no longer present in popular discourse, featured in suburban chicken keeping nor in industrial production, notwithstanding their involvement in the sexual reproduction of more chickens. Curiously the progenitive sperm of the male is often overlooked, and in comparison to battery sheds or meat rearing sheds industrial breeding sheds are rarely featured in exposés by animal activists. The common presence of rooster weathervanes on Christian churches is one of the only remnants of a once prevalent domesticated bird and its associated architectures.[04] And yet cockfighting pits, arenas, and cockfighting husbandry record were not only some of the first architectural engagements with chickens, but significant social constructions. The cockfighting pits and arenas (hereafter simplified to cockpits) of England were purpose-built spaces of action. They were small theatres in the round with an elevated cocking table as the stage. This table was a key feature of English cockfighting, and so central and recognisable to the ‘sport’ that improvised cockpits could be set up spontaneously simply by placing a carpet over a large round table.[05] Despite their popularity there is scant documentation of cockpits, however there are notable examples, usually where these were maintained by the upper classes. Andres de Laguna wrote in 1539 about King Henry VIII’s cockpit at Whitehall, describing this as a “sumptuous amphitheatre of fine workmanship.”[06] This suggests that these were not fringe, inconspicuous structures. On the contrary, they were found in palaces, nobles’ estates, London streets and churchyards.[07] The assortment of miniaturised gallinaceous gladiatorial spaces were significant entertainment structures for an extended period. Cockfighting was only outlawed in England by Queen Victoria in 1849.[08]

Where, and when, the bloodsport is outlawed, the cultural roles of the once celebrated masculine birds change. Most cockfighting birds confiscated from illegal activities, for example in the United States, are euthanised.[09] These chickens are trapped in systemic violence, and it is considered unnecessary to rehabilitate or save them.[10] In industrial settings chickens are likewise treated expendably, for example many industrial egg farms forgo rehoming older birds such as ex-laying hens. Yet there are organisations that gather spent hens and successfully rehabilitate them into backyard flocks.[11] In the case of ex-cockfighting roosters, the perceived masculinity associated with cockfighting is no longer believed acceptable to the Global North and the rooster’s hyper-maleness is assumed not conducive to human (or humane) society.[12] This differential treatment is revealing, not only across the gendered identities of chickens, but across the treatment of the species, if dogs were the focus of this research this treatment would yield a very different reaction. It is contradictory that cockfighting is a violation of animal welfare laws, when those same birds are exterminated when found by servers of justice. Likewise, the ruthlessness associated with cockfighting can trigger outrage from the same public who turn a blind eye to the mass exploitation of chickens in industrial settings. This is not to support cockfighting but to point to the perception of cockfighting as somehow worse than the prevalent cruel, highly exploitative, and legal industrial practices.

The husk of the rooster’s stripped body is a screen used by humans to project an artificial and programmed masculinity. A version of masculinity that I describe later as counterfeit and inauthentic. The birds here are dubbed, de-crowned and in conflict. This dangerous projected masculinity historically accorded men political and social influence in the theatre of the cockpit. Today it has strangely permeated the internet, social media and has become embedded into computer algorithms.

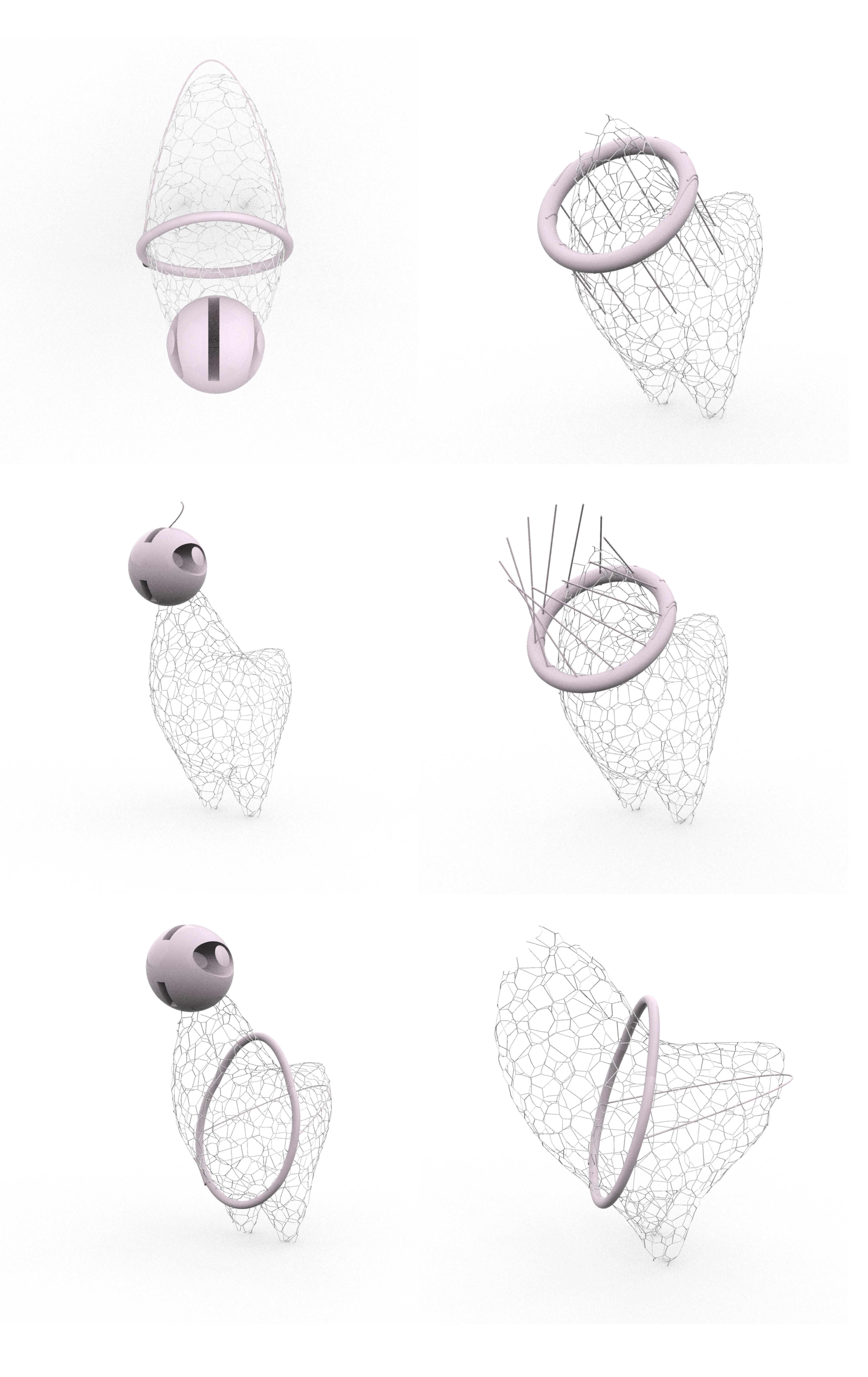

Possible alternative additive body modifiers are used to re-think ways a rooster could be re-adapted to a different human–chicken relationship. How could manipulating vision, regulating their ability to crow, or restricting their movement force the rooster’s body into a prescription of the non-threatening hen? The emphasis is placed on restructuring the roosters sensory experience, vision, or speech. Ideas in modulating the rooster into a creature compatible with urban suburban sites that exclude the roosters’ masculine traits: spurs, crows, crowns, and territory. These also became digital sketches. Ultimately these ideas are tested intellectually against the rooster mannequin – a blank chicken screen. As a PLA Voronoi mesh mannequin, it represents the feathered volume of the bird with wings closed. It has no feet, tail or head.

Adapting a body: deformation, captivity and appendages

Human-built chicken architecture, although not often included in the architectural canon, is a core feature of the poultry industry today as it regulates daylighting, confines birds and controls their contact with wild fauna.[13] Cockpits have not been framed as part of this disciplinary regime, which is surprising when cockpits once fell directly under architectural consideration, with examples being renovated into multi-use theatres by the likes of the historically notable architect Inigo Jones.[14] Again, this observation is not intended to see something positive in cockfighting, but to point to how roosters had only been part of our spatial consciousness when securely associated with human perceptions of masculinity. These echoes from the past make the female egg layer and the male combatant the most prevalent material and cultural roles for chickens in human–chicken relationships but the once-gallinaceous gladiators have been removed from design consideration and are on the discourteous side of sexual cultural binaries. Roosters are reserved for weathervanes and cocks for cockpits.Male chickens have become fringe societal members whose bodies do not fit. The present binaries such as caged/free, commodity/companion, or sustainable/unsustainable are words reserved for hens. Chicken and hen, as words, are used to represent the same animal. Cock, as a word strongly paralleled to masculinity, has a discourteous association. The male chicken body does not naturally conform to cockfighting; it must be conditioned and physically moulded to this human practice. How the body of the fighting cock is manipulated for sport is startling. Feathers are cut and plucked; the removal of the bony spurs from the bird’s legs is commonplace, as is dubbing, which is cutting away the bird’s wattles, and de-crowning the bird, cutting away their crown or comb.[15] Most of these tissues will never regenerate. This act of violence strips the individual bird of their social identity, as the comb and wattles are important in gallinaceous societies for courtship displays, as well as representing the individual’s fertility.[16] They overtly express the chicken’s position in their flock.[17]

In cockfighting the control of a bird’s physical body is coupled with husbandry practices that influence a bird’s behaviour. A cockfighting rooster is raised in isolation, confined and fully dependant on humans, a universal cockfighting husbandry practice. As a result, cockfighting birds can fight with little provocation, a reflex which is further conditioned with forced mock training battles. Cockfighting, as manifested by human influence, bears no resemblance to roosters squabbling over territory and hens in less regulated social settings. Architecture, as is well-understood in relation to human bodies, is deployed as a conditioning device to modulate avian social interaction and as a disciplinary apparatus. Cockfighting enthusiast and anthropologist Clifford Geertz documented cockfighting birds in Bali as being kept in individual baskets that must be moved through the day to control sun exposure and prevent overheating.[18] Tim Pridgen, a cockfighting enthusiast of the early twentieth century, documented housing stalls in the United States that were used to separate birds. Birds were organised in rows, solid walls between each compartment kept the birds isolated and restrained.[19] Isolating a highly social animal impacts their ability to thrive amongst their own species. They are kept in a constant state of what pattrice jones describes as “sensory deprivation and social frustration.”[20]

This disciplining of the avian body through architecture complicates the gender roles or imaginaries prescribed to chickens; these roles are culturally situated manifestations of human desires and actions, shaped and maintained by the housing and disfiguring of the avian body. The birds accordingly act as an avatar for human social, emotional and cultural constructs. Geertz’s study of cockfighting in Bali revealed how the male chicken is symbolic not only of the bird’s owner’s “narcissistic male ego” but also of “what the Balinese regards as the direct inversion, aesthetically, morally and metaphysically of human status: animality.”[21] The repulsion of animals or being animal-like in Balinese culture, according to Geertz, is why dogs are treated with cruelty and most other domestic animals are viewed without emotion. The cock being unique in that it is a blood sacrifice that ties masculinity to fears and hate, “fascinated by – The Powers of Darkness.”[22] Cockfighting has little to do with authentic chicken behaviours, and more to do with the enactment or construction of human cultural situations and narratives. A fighting-cock isn’t an absent referent to a human idea, but an individual with a tortured lived experience. The cultural perception of chickens and how they are used in cultural performances are supported by individual birds and bodies.

Chickens considered within architecture are often coupled with sustainability projects be it urban farming and backyard poultry keeping, or recreational or holistic retreats. Japanese architect Kengo Kuma, by way of example, brought his signature aesthetic of expressed structure through interlocking and stacked timber to the hen house at Casa Wabi – an artist farm-retreat, founded by Mexican contemporary artist Bosco Sodi. The farm-retreat has the ambition of creating personal encounters with art, “which seeks beauty and harmony in the simple, the imperfect and the unconventional.”[23] The hen house was included as part of Casa Wabi with a focus on communal chicken housing.[24] The walls are made of interlocking plywood panels. Each panel is treated with a traditional Japanese technique in which the wood is charred to make it weather and insect resistant.[25] Designs for chicken husbandry units have also emerged as commercially available products for the purpose of self-reliance and more localised sustainable food production. Eglu™ by Omlet©, for example, is promoted as a solution to urban chicken keeping.[26] Through a multi-site ethnographic project on urban livestock, Shona Bettany and Ben Kerrane have found that the Eglu is “an ambivalent object,” one that enacts, “co-producing binaries of consumption/anti-consumption and resistance/domination.”[27] The human activity of building enclosures for chickens is most often for the purpose of controlling and encouraging egg laying. Hens have become the pin-up girls of permaculture, viewed as a model for regenerative farming. Hens are often used for the benefit of humans, and this includes symbolically, as a suggestion of sustainability that selectively disregards the ethical dubiousness of such uses.

Even so, cockfighting is the antithesis of our permaculture pin-ups in a few keyways; it is extractive, ritualistic, and unabashedly performative. In Griselda Pollock’s ‘Cockfights and Other Parades,’ Pollock says of Geertz’s work:

“the fight itself must be read as a kind of blank screen… The sport of cockfighting is a displaced and educating mirror image of social relations of masculinity and social power in which animal savagery and male narcissism, status rivalry and individual emotion, blood, sacrifice, and rage, are built into a structure of representation which allows them both visibility and play.”[28]

Re-imaging, re-projection, and re-dressing the fighting-cock

The manipulation of the male chicken is primarily facilitated through human-built boundaries. The birds are pitted against one another in a carefully understood space of action; their territorial tolerance exploited to an extreme degree. These frustrated birds are equipped with gaffs or long-knives attached to their legs. Their natural spurs are replaced by human-crafted weapons, ensuring a bloody spectacle. The bird is usually only freed from this gruelling existence when death meets them in combat or – less commonly – when they are ‘saved’ from an illegal cockfighting ring only to be euthanized by animal control agencies.Cockfighting recalls outdated masculine forms of entertainment that are not deemed compatible with contemporary, progressive society. However, raising hens for egg laying is viewed as nurturing and peaceful. Re-chickening suburban or urbans spaces cannot happen without re-dressing cultural prejudices that negatively portray all chickens as either gladiators, machines, or resources to exploit.

The mannequin stripped of maleness could become a host for any projection; it presents a surface for a new understanding of a current abject being. It only echoes a chicken and the longer history of a ground dwelling avian species.

The domestic chicken, albeit with a focus on the hen, has emerged as a catalyst for design. One example is Austin Stewart’s Second Livestock which proposed a virtual reality headset as a stress reducing alternative to free-range birds.[29] Stewart’s headset would shield chickens from the perceived dangers of the outside world, keeping them confined in boxes with visual scenes of pasture grazing. Another example is Dezeen’s June 2020 publication “Five chicken coops around the world,” which showcased architect-designed chicken enclosures, predominately for backyard chickens.[30] On Dezeen’s webpage there was – as expected – a focus only on hens and egg production. There is a more complicated cultural history around keeping chickens and the labour that this entails which cannot be properly unpacked here, but it is notable that domesticated chickens are more similar than dissimilar to their wild forbears who roost in trees and nest on the ground.[31] The emphasis on chickens in design is on the notion that chickens require housing or an enclosure, to separate and protect them from the outside influences.

These projections, although executed simplistically and roughly, echo how the exterior shell of a singular being have captured human social values. The cockatrice is the male with female traits, a male who lays eggs, captured in fables as a deviate and unnatural progenitor. The colonel and military figure a version of masculinity that shaped the colonial conquest and control of world politics and influence. The antiquated view of aggressive masculinity is what underpins the history and roots of patriarchal property rights and legal policies that gave power of governance to one form of male human body.

These constructs are what the design exercise which prompted these reflections aimed to challenge. By concentrating on a male chicken’s body, a closer scrutiny of human culture is realised. Seeing this body as a blank screen, the avian body becomes the site of projection for human ideas of masculinity. Through this blank space the symbolic role of the bird is established, allowing him to be placed in the circular, spectacular, space of the cockpit. He is morphed through this action into a symbolic façade, a totem to masculinity, courage, and valour. The avatar is immortalised as a gladiator. Or, is emblematic of other entities; as described by Robert Howlett in 1709, they can be astronomers, alarm clocks, and military leaders.[32] The fighting-cock, no longer a living bird, is an avatar for receiving imagery that is imposed on him. The bird’s performance, an exploited behaviour, plays out a story written by their handler. The mannequin of the cock, produced for the sake of reimagining this story, becomes a site for design, a mythological space, a chicken shaped blank canvas. It represents the nonhuman animal as a site of projection for the avatar.

Denuding the model with linen set a stage to re-dress the male chicken body as a protheses for human projections and performance. Following the preparation of the model I turned towards Rebecca Horn’s work, and Vito Acconci’s Head Theaters. In Horn’s Unicorn, the costume, or instrument, built associations between Horn’s fellow student and a mythical beast, “a symbol of purity, chastity and innocence.”[33] The unicorn is the opposite of the fighting cock, and of the maleness associated with roosters. Here, another mythical creature challenges this maleness: the mythical cockatrice, a part rooster creature, so foul that a person who looks upon it turns to stone. The cockatrice symbolises unnatural generation, “the rooster’s egg lacks the progenerative grain or germ” to quicken a chick.[34] Horn’s work is used here to expose the gendered inconsistencies of reproductive purity and sexlessness set against virility and maleness. Another inspiration from Horn’s work for equipping the fighting cock is that her work emerged from her longing to connect with others through intersubjective relations between performers.[35] What Lynne Cooke refers to as alienation, loss, betrayal, isolation, loneliness, and despair.[36] Social connections are withheld from roosters in cockpits and cockfighting conditioning. Rebecca Horn’s Body Sculptures, as understood by Diana Bularca, are not prostheses replacing missing body parts, but instruments that redefine the senses.[37]

Where denuding the chicken focuses on loss, redressing the male chicken focuses on the performative projection of the avatar. Vito Acconci’s work has a performative dimension that are difficult to reduce to linguistic models.[38] Head Theaters, for example, is a 3D proposal of a panoptical theatre, where grey blocky digital humanoid forms peer into individual viewing ports.[39] There is no explanation as to what the figures are observing or if it the same or a different performance. Similarly, the chicken mannequin was re-developed as a screen or pseudo stage. A human user looking upon it bears witness to projections of a mythological creature, a military general, an astronomer or other culturally prescribed performances. Katharina Fritschs’s Hahn/Cock – a 6m blue cock which was originally erected in Trafalgar Square in London in 2013 – is brought into these re-presentations as a male character re-evaluating his own form, a chicken perspective on human projections.

Reimagining the Fighting Cock: The Body of the Avatar

In the images and collages provided, the male chicken, a minutely scaled bird, and single being, is employed as an avatar projected to a supernatural scale. A small red feathered being, acting as reinforced by pattrice jones, out of fear, isolation and abuse.[40] He is materialised outside of himself as a prothesis for human intentions. Human mythologies are cast upon him in a performance. Through this work this process of materialisation is put into question. The shift from digital avatar to pink cellular tissue suggests the development of the chicken screens as spaces for confrontation with material imaginings. In physical form, the de-sexed mannequin can become any chicken: hens, pullets, cockerels and chicks, all could enter the projection. Imagining the mannequin, adapted again into an installation, multiplies projections, mirrors – or a series of mannequins overlaid and overlapping in a multi-faceted projection of human and non-human cohabitation. The vocalisation of chickens can be heard alongside urban and suburban noises, depictions of chickens in current industrialised settings (the meat chicken shed, the battery, the breeding shed, and barn-laid egg systems) with their associated human-centric spaces (suburban backyards and supermarkets). The avatar is a tool for critique and intellectual re-dressing and re-imagining.The form of masculinity that is displayed through cockfighting is a dangerous and inauthentic maleness. The reality that it must be conditioned into chickens through an architectural disciplining (confinement, separation, environmental control), social isolation and physical harm showcases that what is being presented here as masculinity is more aptly antisocial behaviour; this is a ‘hyper-maleness’ ‘not conducive to human society’, a counterfeit masculinity. Roosters left with their own kind are raised in a social group which includes diverse members in addition to their own mother and father. Roosters also play an active role in their families, observed in wild populations as helping with nest site selection, calling when they find high value food, and providing protection.[41] Chicken masculinity is not reducible to aggression, as chickens are part of a unique avian community. Humans are solely responsible for hyper-masculinising chickens. My work has emerged at a problematic time when dangerous human masculinity is gaining traction. Where cockfighting is still considered taking things too far – banned in much of the Global North – there has been an uptick in regressive political discourse intentionally hindering women. Josephine Browne, a researcher in masculinities, eloquently parses the problems with the current term ‘toxic masculinity’, which fails to account for the history that has created current sexual politics.[42] There are striking parallels in how social conditioning and isolation are used in roosters, boys, and young men to create a form of masculinity rooted in antisocial behaviour.

If suburban and urban spaces are to be re-chickened, especially around notions of a more sustainable farming method, the chicken must be re-sexed. Chickens cannot regenerate without a representation of both sexes. Cockfighting is an artificial human practice that does not need to define a male chicken. Hens are also more than egg generators, they are mothers, friends, and partners. Andrea Gaynor observed that local food production in Australia was once, “widely seen as a symbol of the self-reliance or independence,” of a respectable working class.[43] Suburban chicken keeping has had a resurgence over the past few decades in the guise of re-equipping citizens with the ability to feed themselves. Yet roosters are erased from these settings. Living with chickens depends on our ability to separate the individual animal from mythological, poetic and cultural projections.

The design research through this project acts as a tool to reinterpret our projection onto the nonhuman avatar to reimagine shared human–animal spaces. Chickens are entrapped in human projections focused on gender and exploitation. In Brisbane there are issues with surplus unwanted and forbidden pet roosters as the city’s residents are not legally able to house them, despite the acceptance of backyard hens. The mythologies built by humans around roosters position them outside of sustainability models for no reason other than their sex. Rooster vocalisations, for instance, have recently been excluded from urban spaces. Letting go of current gendered perceptions of chickens could be one stepping stone towards a more-than-human way of living. As it stands, gladiators have become ghosts, and the mothers have moved toward machines; yet, for each individual chicken, they have always lived as complex social birds.

Published 10th November, 2025.

Notes

[01] Conference Organisers, Brief to participants in the Re-appropriation and Representation symposium, 30th October – 1st November 2020.

[02] Carol J Adams, The sexual politics of meat: A feminist-vegetarian critical theory (Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2017), 62.

[03] Karen Davis, Prisoned chickens, poisoned eggs : an inside look at the modern poultry industry, Rev. ed. (Book Publishing Company, 2009), 35, 56, 66–67.

[04] This tradition is rooted in Christian biblical stories. See: Alan Powers, Conversations with Birds: The Metaphysics of Bird and Human Communication (Simon and Schuster, 2023), 147.

[05] Jack Gilbey, “Cockfighting in Art,” Apollo, vol.65, no. 383 (1957).

[06] John Orrell, The Theatres of Inigo Jones and John Webb (Cambridge University Press, 1985), 92.

[07] Gilbey, “Cockfighting in Art,” 22.

[08] Annie Potts, Chicken (Reaktion Books, 2012), 19.

[09] Amir Efrati, "When Bad Chickens Come Home to Roost, Good Things Can Happen Pair Rehabs Drugged Gamecocks Felipe Finally Gives Up the Fight" (Victoria, Hong Kong: Dow Jones & Company Inc, 2005), accessed 22nd May 2025. https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB112138977056286436.

[10] There are scant chicken rescues, and even fewer for ex-cockfighters. VINE Sanctuary, cofounded by pattrice jones, is one of the few ex-cockfighting chicken rescuers and rehabilitators in the US that also work to reveal the gendered dynamics of chickens in human societies. pattrice jones, "fighting cocks: Ecofeminims Versus Sexualised Violence," in Sister Species: Women, Animals and Social Justice edited by Lisa Kemmerer (University of Illinois Press: 2011).

[11] Catherine Oliver, "The Chicken City: Urban Interspecies Sociabilities," in Human-Animal Relationships in Times of Pandemic and Climate Crisis (Routledge, 2024).

[12] pattrice jones, "Roosters, hawks and dawgs: Toward an inclusive, embodied eco/feminist psychology," Feminism & Psychology, vol.20, no.3 (2010).

[13] Natalie Lis, "Forest Birds on Pasture: Meddling Marketing and Conflicting Cultures," Animal Studies Journal, vol.13, no.1 (2024).

[14] See: Orrell, The Theatres of Inigo Jones and John Webb, Chapter 3 “The Cockpit in Drury Lane” and Chapter 5 “The Cockpit-in-Court.”

[15] The wattles are the flesh beneath their lower beak and the crown runs atop their head.

[16] Glen McBride, I.P. Parer, and F. Foenander, "The social organization and behaviour of the feral domestic fowl," Animal Behaviour Monographs, vol.2 (1969): 152.

[17] Dominant chickens having larger and more vibrant tissues that change throughout their lives. Elizabeth Fessler, Marlene Zuk, and Torgeir Johnsen, "Social Dominance, Male Behaviour and Mating in Mixed-Sex Flocks of Red Jungle Fowl," Behaviour, vol.138, no. 1 (2001): 13.

[18] Clifford Geertz, "Deep Play: Notes on the Balinese Cockfight," Daedalus, vol.101, no.1 (1972): 6.

[19] Tim Pridgen, Courage, the story of modern cock-fighting (Little, Brown and Company, 1938), 37.

[20] jones, "Roosters, hawks and dawgs," 369.

[21] Geertz, "Deep Play: Notes on the Balinese Cockfight," 6.

[22] Geertz, "Deep Play: Notes on the Balinese Cockfight," 7.

[23] “About”, Fundación Casa Wabi, accessed 21st May 2025, https://casawabi.org/en/about/.

[24] Bridget Cogley, “Kengo Kuma builds blackened-wood chicken coop at Casa Wabi artist retreat,”Dezeen, 20th June 2020, accessed 22nd May 2025, https://www.dezeen.com/2020/06/20/casa-wabi-coop-kengo-kuma-mexico/

[25] Cogley, “Kengo Kuma builds blackened-wood chicken coop at Casa Wabi artist retreat,” Dezeen, 20th June 2020, accessed 22nd May 2025, https://www.dezeen.com/2020/06/20/casa-wabi-coop-kengo-kuma-mexico/

[26] Potts, Chicken, 176.

[27] Shona Bettany and Ben Kerrane, "The (post‐human) consumer, the (post‐avian) chicken and the (post‐object) Eglu," European Journal of Marketing, vol.45, no.11-12 (2011): 1748, 1754.

[28] Griselda Pollock, "Cockfights and Other Parades: Gesture, Difference, and the Staging of Meaning in Three Paintings by Zoffany, Pollock, and Krasner," Oxford Art Journal, vol.26, no.2 (2003): 152-53.

[29] Christianna Reedy, “A VR Developer Created an Expansive Virtual World for Chickens,” Futirism, 16th May 2017, accessed 21st May 2025, https://futurism.com/a-vr-developer-created-an-expansive-virtual-world-for-chickens

[30] Bridget Cogley, “Five Chicken Coops around the World,” Dezeen, 22nd June 2020, accessed 21st May 2025,https://www.dezeen.com/2020/06/22/chicken-coops-architecture/.

[31] Lis, "Forest Birds on Pasture."

[32] Robert Howlett, The Royal Pastime of Cock-fighting: The art of breeding, feeding, fighting, and curing cocks of the game (D. Brown and T. Ballard, 1709), B4.

[33] “Unicorn,” Tate, accessed 21st May 2025, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/horn-unicorn-t07842.

[34] William R. Newman, "Bad Chemistry: Basilisks and Women in Paracelsus and pseudo-Paracelsus," Ambix: Paracelsus, Forgeries and Transmutation, vol. 67, no.1 (2020): 43.

[35] Diana Bularca, "Rebecca Horn: devising intersubjective connections," World Art, vol.9, no.3 (2019): 331.

[36] Lynne Cooke, "Horn’s Sensorium: Site and Source of Desire," in Rebecca Horn: The Glance of Infinity. (Kestner Gesellschaft, 1997): 27.

[37] Bularca, "Rebecca Horn: devising intersubjective connections," 334.

[38] Monica Manolescu, "Vito Acconci. Spaces of Play," Transatlantica, vol.2, no. 2 (2013): 9-10.

[39] “Head Theaters,” Acconci Studio, accessed 21st May 2025, http://acconci.com/head-theaters/.

[40] See: jones, "Roosters, hawks and dawgs."

[41] Bruce A. Webster, "Behavior of chickens," in Commercial Chicken Meat and Egg Production, edited by Donald D. Bell and William D. Weaver (Springer US, 2002), 71-86.

[42] Josephine Browne “Why the phrase ‘toxic masculinity’ is an obstacle to change,” Overland Literary Journal, accessed 21st May 2025. https://overland.org.au/2019/11/why-the-phrase-toxic-masculinity-is-an-obstacle-to-change/.

[43] Gaynor focuses on the Australian postwar history of backyard chicken keepers. See “Fowls and the Contested Productive Spaces of Australian Suburbia, 1890-1990” in Animal Cities: Beastly Urban Histories, edited by Peter Atkins (Routledge, 2016), 213.

Figures

Banner.

Cosmic Chicken: Mannequin of an Abject Being. Photocollage. Natalie Lis.

01.

How to script a Chicken, generated Chicken Model and Voronoi script, leading to wire frame model generated in Rhino, and 3D printed pink husk. Natalie Lis.

02.

Hen, Chick, Rooster, Female, Neuter, Male: Exploring Ritual, Colour and Genders of the Chicken Body. Natalie Lis.

03.

Weathervanes. Natalie Lis.

04.

Projected Bodies: Dubbed, De-Crowned, In Conflict (Variations 5 and 6). Natalie Lis.

05.

Body Modifiers, Rooster Mannequins. Natalie Lis.

06.

Cosmic Chicken: Mannequin of an Abject Being. Natalie Lis.

07.

Projected Bodies: Cockatrice, Colonel, Blank Slate (Variations 1, 2 and 4). Natalie Lis.

https://doi.org/10.2218/r28fgj13