Re-Appropriating Image/Xiang: A Cosmotechnics of clay

Leo Xian

In his 1964 article “The End of Philosophy and the Task of Thinking,” Heidegger writes:

“The end of philosophy means: the beginning of the world-civilization will be based on Western European thinking.”[01]

Cybernetics will, he argues, bring Western European thinking to completion, and as a result world civilization will be grounded in this tradition. Our current understanding of media and technology operates from this tradition, and from a narrow concept of technics associated with Heidegger’s philosophy. This, too, was anticipated by Heidegger. In his 1949 lecture “The Question Concerning Technology,” Heidegger distinguishes the Greek technē from modern technology: while technē embodies poiesis – a poetic process of bringing forth – modern technology has lost this essential dimension.[02] In what follows I explore an alternative understanding of technology, and the role of the image and representation in conceptualisations of technology, through the Chinese philosopher Yuk Hui. Responding to Heidegger’s attempt to step back to a cosmology centred on the non-rational Being (Sein), Hui proposes the speculative concept of cosmotechnics. A prominent thinker in the philosophy of technology today, Hui draws on both Western philosophy (notably Heidegger, Simondon, and Stiegler) and Chinese thought to offer a critical framework for rethinking the relationship between technology and cosmology. Hui seeks to move beyond a Eurocentric model of technicity by proposing a situated cosmotechnics which promotes techno-plurality. Strangely, this search has its beginnings in Western Europe, and a prior attempt to move beyond Heidegger. Hui follows the French sinologist François Jullien’s exploration of traditional Chinese aesthetics, in which Jullien sees – via a detour through the Chinese tradition – a potential response to Heidegger’s critique of Western philosophy, particularly its historical domination by eidos (form) within the history of metaphysics. Heidegger challenges the language of form – of presence and absence – that underpins Western philosophy by seeking an opening, a clearing, an unthought.[03] In contrast, Jullien observes that Chinese thinking does not draw a sharp distinction between absence and presence. Thus, ontology – the search for the mastery of Being – familiar to western philosophy has never been a significant question in Chinese thought. Absence and presence remain unified.[04] Rather than pursuing the question of form as understood in the West, Hui – developing Jullien – focuses on the xiang (image, 象) in the Daoist tradition of Laozi, who wrote: “the great xiang(image) has no form (大象無形).”[05]

For Hui, cosmotechnics – operating within the tradition of the xiang, “seems to exemplify an encounter through which technology inscribes Dao(the way, 道) into its operation and structure.”[06] Hui observes that the decline of the Chinese aesthetic tradition was caused by the increasing separation of Dao (the way, 道) and Qi (tools or vessels, 器)[07] during the Qing dynasty, which led to the Modern Chinese Language Revolution,[08] Chinese modernity and the collapse of the traditional Dao-Qi correlation system.[09] This paper will reflect on the relation between Dao and Qi, or we might say between ‘ways’ and ‘tools’, through a further cosmotechnical speculation, a response to what Hui describes as the on-going “bad infinity of mono-technologism.”[10] I take this ‘bad infinity’ to be a consequence of a belief in a universal, hegemonic technological system based on the Western model of progress and development, in which, at the scale of nation-states, “competition based on mono-technology is devastating the earth’s resources for the sake of competition and profit, and also [preventing] any player from taking different paths and directions.”[11] Developed within the Western philosophical tradition that culminated in cybernetics – a mid-twentieth-century theory of logical systems involving feedback, automation, and data-control – digital media technology has largely been shaped by, and in turn has infrastructured, this mono-technological system, which produces a singular techno-globe.[12]

This cosmotechnical speculation builds on and probes Hui’s position on technics. In his book On the Existence of Digital Objects (2016), Hui points out that while digital objects (applications, programs, websites, etc.) still have a physical and spatial presence through devices and machines, their modes of existence differ significantly from traditional technical objects – such as Heidegger’s jug. A jug constitutes a technical environment grounded in specific material and cultural practices that evolve over time; its void – mediating between the human individual and water – acts as a site that embeds human being in the world by holding and pouring water.[13] In contrast, digital objects exist in an enclosed, preprogrammed context, detached from the world of particular localities, environments, and cosmologies. Here, the human individual’s role is “always already anticipated, if not totally programmed.”[14] To break away from the current enclosed circle created by mono-technologism, cosmotechnics is proposed as a way to re-situate technology locally, in alignment with the cosmology, geography, and imagination of a specific culture. In simple terms, cosmotechnics is defined as “the unification of the cosmos and the moral through technical activities, whether craft-making or art-making,” with the aim of envisioning a future of technical plurality.[15] Against the escalating global crisis developing before us, Hui argues:

“There hasn’t been one or two technics, but many cosmotechnics. What kind of morality, which and whose cosmos, and how to unite them vary from one culture to another according to different dynamics… it is necessary to reopen the question of technology, in order to envisage the bifurcation of technological futures by conceiving different cosmotechnics.”[16]

In what follows I aim to explore, through text, image, and image-text, one particular form of technics, here positioned as Scripto-technics, which questions technologies of writing that privilege the separation of Dao and Qi. This Scripto-technics has been developed and will be described through text and an associated design-research project.[17] The site for this project is a room – My Room – captured using a LiDAR scanner during the Covid-19 pandemic lockdown, a suspended moment that marked the onset of a broader and ever-intensifying contemporary apocalyptic sensibility. Conceived as a small and personal fragment of a much larger generational experience of existential crisis, the room is subsequently reinscribed in clay as a new architectural text: a set of developed “Chinese characters,” spatially situated, bringing together multiple technics through technē.

Developing Cosmotechnics: Making Scripto-Technics

The nuances in the term image/xiang in Chinese, the interplay they suggest between presence and absence, are lost in the digital age, where “image” refers only to what is present to the senses and can be stored as data. In Signal. Image. Architecture., the architect John May argues that in the current digital age, where society is governed by the Cloud of data, “everything is already an image.”[18] The image today is essentially “a form of photon detection,” through which “all imaging is an act of data processing.”[19] Instrumental gestures of “touching, swiping, scrolling, selecting…” in image processing have become the gestural basis of an entire consciousness of telemasis.[20] Reflecting on a similar set of preprogrammed gestures in the so-called digital Sinosphere, the sinologist Jing Tsu remarks:“Swipe. Tap. Drag. Chinese smartphone users can mix those three motions with their thumbs at an astonishing speed on the touch screen…One scarcely has to learn Chinese the hard way – by memory or by hand – anymore, it seems…It took a century of effort – from the adaptation of national dialect to the engineering of efficient digital character encoding – for the Chinese to benefit from the reach of that precision.”[21]

Hui cautions against such benefits; writing in such a manner is taken only as an abstraction of meaning, undermining the existential embodied relations it has with the external world.[22] In a digital system, Chinese writing – a practice of tracing and embodying rich narrative relations – has been Romanised and reduced through an input system based on the twenty-six letter English alphabet. As a result, the technical tools/Qi of writing have been separated from the Way/Dao of its cosmos. In contrast to the digital systems which privilege presence and the known as objects of representation, the Chinese cosmos of Dao “does not imply presence, as Dao is deep and remote.”[23] As described in the Laozi (Dao De Jing, 道德經),“Dao is shadowy, indistinct. Indistinct and shadowy, yet within it is an image/xiang.”[24] The cosmotechnics of Chinese writing serve as a means of conceiving the shadowy image of Dao – an opening towards the unknown. One possible mode of cosmotechnics – explored below – aims to depart from the representation of machine intelligence in digital text by restoring the unknown as the object and aim of writing, acknowledging the incalculability of being in the world. After Hui, writing here becomes both an art and a form of intelligence: “in order for any intelligence to produce art, its object cannot be the known, but the unknown... (It is) something that cannot be entirely grasped and demonstrated objectively.”[25] Similarly, the image/xiang of Dao is embodied in the spatial and material practice of Chinese writing as a means of unknowing. Through the notion of Scripto-technics I aim to suggest that the key to re-appropriating the Chinese notion of image/xiang lies in the reawakening of a material practice and, through it, an enriched and diversified gestural figuration and associated bodily consciousness. To re-situate modern technological tools (Qi) such as the 3D LiDAR scanner and the 3D printer on the ground of the unknown, I elaborate this figuration through three gestural practices (ways/Dao) – tracing, moulding, and sketching – which I am here describing through a correlation of Dao-Qi.

Dao-Qi/Ways-Tools I: Tracing

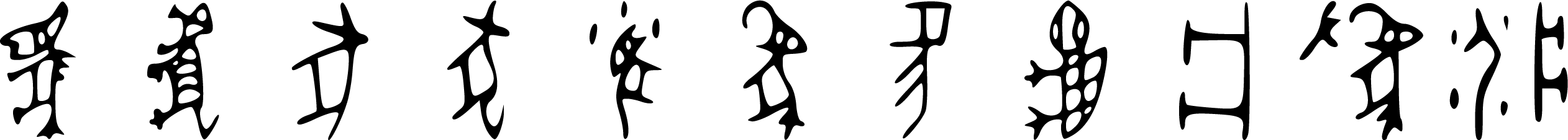

Differing from both Western phonographic and digital writing systems, Chinese writing is understood as “a philosophy of things.”[26] Among the various techniques used to construct its characters,[27] the fundamental structure of Chinese writing is pictographic – its characters are drawings of patterns and phenomena in the natural world, as evidenced in the oracle bone script of the Late Shang dynasty (c.1200-1050 BCE).[28]

01. Oracle Bone Scripts, from the left: 馬 horse, 虎 tiger, 豕 swine, 犬 dog, 鼠 rat, 象 elephant, 豸 beasts of prey, 龜 turtle, 爿 low table, 為 to lead, and 疾 illness.

However, importantly, Chinese writing is not solely based on image-driven models but is also embedded in a bodily sense, functioning as a form of situated technics: “Chinese writing as a practice of traces embeds already rich relations and patterns that could not be identified in phonetic writing... To write is not simply to deliver communicative meaning but also to ponder about the relation between the human and the cosmos.”[29] This embodied relation between the human and the cosmos was present in the very beginning of writing. Speculating on what might have triggered the invention of writing, the Eastern Han philosopher Wang Chong (王充, 27-97 AD) writes in Lun Heng (Discourses in the Balance, 論衡):

以見鳥跡而知為書,見蜚蓬而知為車.

“It is through the observation of bird’s footprints that Cang Jie understood how to form writing, and it is through the observation of Feipeng flowers that Xi Zhong understood how to make chariots…”[30]

There is an apparent parallel between the invention of Chinese writing – based on the footprints of birds – and origin of painting in the West, which centres on the notion of the trace. According to Pliny the Elder, the origin of painting in the Western tradition lies in the story of the “Corinthian Maid,” who traced her departing lover’s shadow on a wall.[31] However, this understanding of the trace as an outlined absence is seen by Jullien as a form of deposit-trace – an absence that lingers, waits, and signifies a hidden presence. In contrast, the Chinese notion of the trace exists precisely between “there is” and “there is not,” and is considered, at once, a presence-absence. “It is present but inhabited by absence, and, if it is sign of, it is of taking leave. Both empty and full, concretely formed and evasive, tangible, and yet escaping at the same time.”[32] As a speculative means of engaging with the subtle parallels and differences of the trace in the Western and the Chinese traditions, and reflecting how Chinese pictograms originate from “cosmic inscriptions”[33] in the forms of animal or bird tracks, the LiDAR scan data of my room (focusing on shadows, aberrant moments the edges) are mapped and digitally scripted as vectors to be transferred onto terracotta clay surfaces. This process translates patterns of light into abstracted signs.[34]

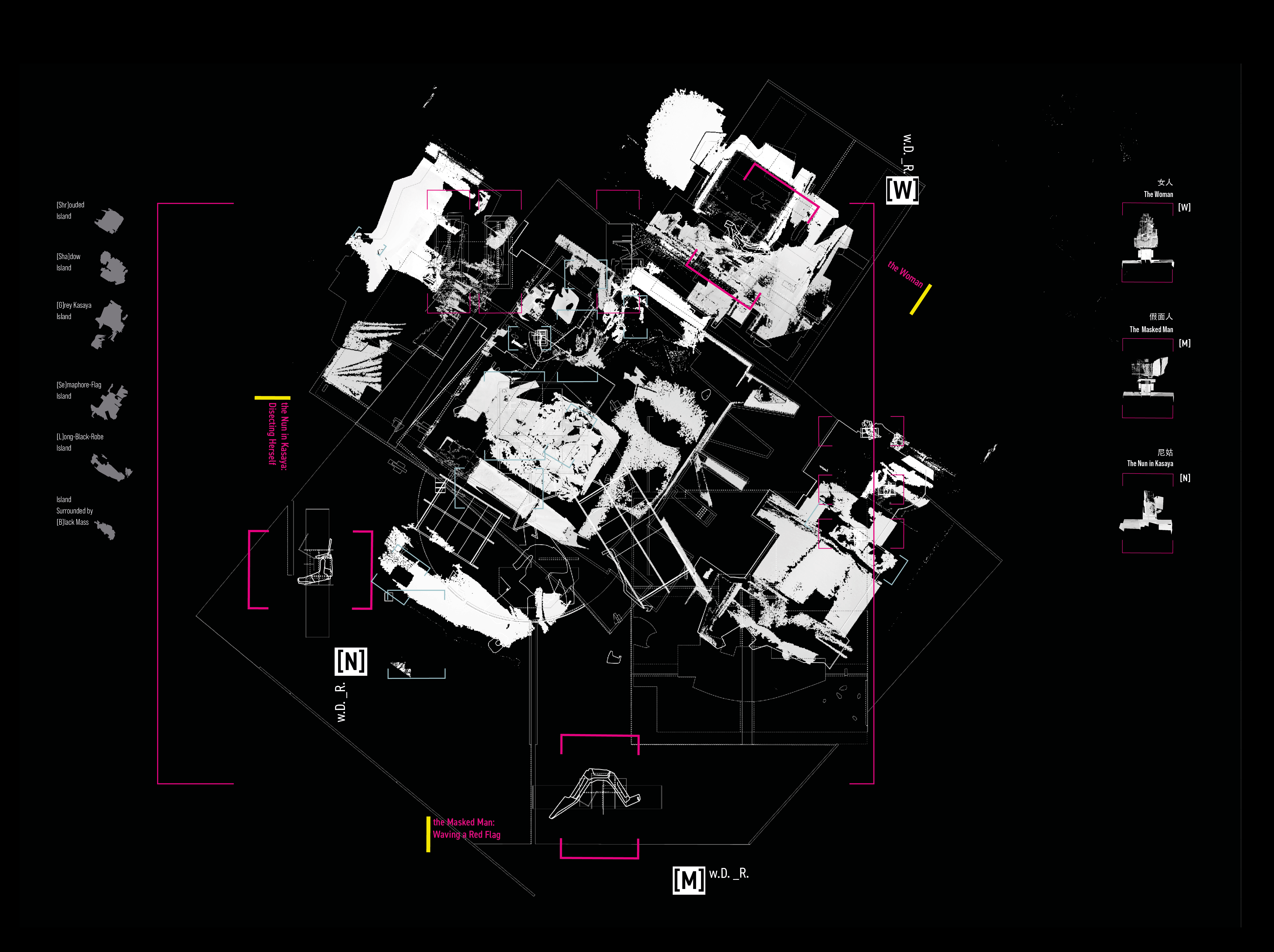

02. LiDAR Scan of My Room, and

03. Inventing new Chinese characters based on LiDAR scanning patterns of My Room. The scanning patterns are scripted as characters according to the Chinese writer Gao Xingjian’s play Between Life and Death (1991).

03. Inventing new Chinese characters based on LiDAR scanning patterns of My Room. The scanning patterns are scripted as characters according to the Chinese writer Gao Xingjian’s play Between Life and Death (1991).

It is believed that the earliest archaeological evidence of Chinese writing – a prototypical Chinese script – consists of a wide variety of two- and three-stroke marks found on pottery fragments from the late Neolithic period (around 4800 BCE).[35] Hundreds of pieces of marked pottery of the Neolithic Yangshao culture have been discovered at the Banpo and Jiangzhai archaeological sites in Xi’an. These signs were mostly incised with tools such as sharp stone, wood, bone, or bamboo knives on the black band running around the outer rim of red pottery vessels before firing. The signs are mostly simple, ranging from “single vertical strokes, to double vertical strokes, T and Z shapes, hooks, combs, and crosses.”[36] Tracing echoes the invention of Chinese script, emphasizing the process of embodiment, from digital data onto the surface of a living, organic material. It is a first step in spatialising and situating digital data in a local, tangible environment.

Dao-Qi/Ways-Tools II: Moulding

The in-betweenness of the trace is then expressed through the act of moulding. Moulding is understood here as neither ‘without’ nor ‘in’ but between:“Whereas without makes us abandon the concrete and deprives us of it, and in makes us stick to the concrete and get bogged down in it, between lets us move freely (spiritually) through the concrete and keeps it communicating-operative.”[37]

3D printing was used to create moulds through which terracotta clay was fashioned. Designed to simulate the ancient principle of clay building, the technology of 3D printing operates with the efficient coiling method. When used as a mould, the coiled PLA strips leave their distinct texture on the surface of the clay, registering the working process. The moulding and demoulding of the clay involved a careful process of monitoring and controlling the microclimate daily as terracotta is very responsive to the humidity and temperature of its surrounding environment.

04. Moulding, sculpting, sketching, and naming with terracotta clay (unfired).

Beyond technical considerations, moulding – an intricate process in which one material surface shapes and fashions another – invites deeper reflection on the “between.” This between (Dao-Qi) that is conceived as the ways/Dao that simultaneously situates and is instituted by the tools/Qi. Rather than focusing solely on the making of objects, the act of moulding draws attention to the subtle balance of an in-between state – what François Jullien describes as an allusive distance that is “not quitting, not sticking.”[38] Jullien invites us to consider the activity of making at the dawn of every civilization: the fashioning of clay to make a pot, and asks, what does the “between” – the hollowed-out clay pot teach us? The clay pot holds, collects, and pours out, and from its readiness-to-hand, pure utility, Jullien considers the clay pot no longer as an image of anything, without any symbolic meaning to interpret, and no mytho-religious scence to ponder, without any need for reference.[39] Viewed through the lens of the “between,” moulding aligns with what the Daoist text Zhuangzi describes as the allusivity of writing: “Without anyone referring, there is reference,” and yet, “while referring, there is no reference.”[40] On this “between” – this allusive distance – Jullien observes:

“There is certainly distance, because the sage does not allow himself to be “bound” by the object of a statement, and he takes his leave from whatever is too direct about reference… At the same time, there is a constant allusivity… not “quitting,” yet also never ceasing to be turned “toward” and to “play”.”[41]

Dao-Qi/Ways-Tools III: Sketching

François Jullien views the sketch as the choice to keep the work in its rough state, to regard it:“not as a study or a preliminary drawing but as a full-fledged work, even fuller than the completed work would be… The sketch keeps the work as close as possible to its invention, in the tension of that springing forth.”[42]

The sketch “forces us to think about how much lack and hollowness must be implicit in the work if it is to come about, how much of a void there must be if the work is to remain active and continue to make itself felt.”[43] Here, sharing a sensitivity with the Chinese tradition, Pliny reminds us of the value of a hand lifted from the canvas, leaving the work unfinished – one that “ushers us into the arcana of creation, (and) brings us to the source of the work.”[44] Once detached from the mould, while still wet, the clay surface is written upon, with simple sculpting tools such as a shredder, loop, ribbon, and needle. The surface accepts traces. Contrary to the autonomous control and the mechanical precision of 3D printing that leaves little room for chance and intuition, modelling on a clay by hand is a highly intuitive, sketch-like process.

05. Sketching on the terracotta clay pieces.

With my hand guided visually and tactilely by the clay surfaces moulded from the digital 3D scan patterns – the Way/Dao situates the tools/Qi, rather than being entirely dictated or controlled by them, sketching on clay is a spontaneous response to the registering of any traces of hesitations, uncertainties, any occurrence of errors and accidental marking, bending, pressing, twisting, scratching, even leaving vague traces of fingerprints. It is an improvisation of the hands guided by the intuition of the eyes, responding to an almost primordial sense of rawness the presence of an organic material brings forth. Beyond being a method of artistic practice, it suggests a de-ontological implication inherent in the process of sketching.

The Place of Re-appropriation: Resituating Technology

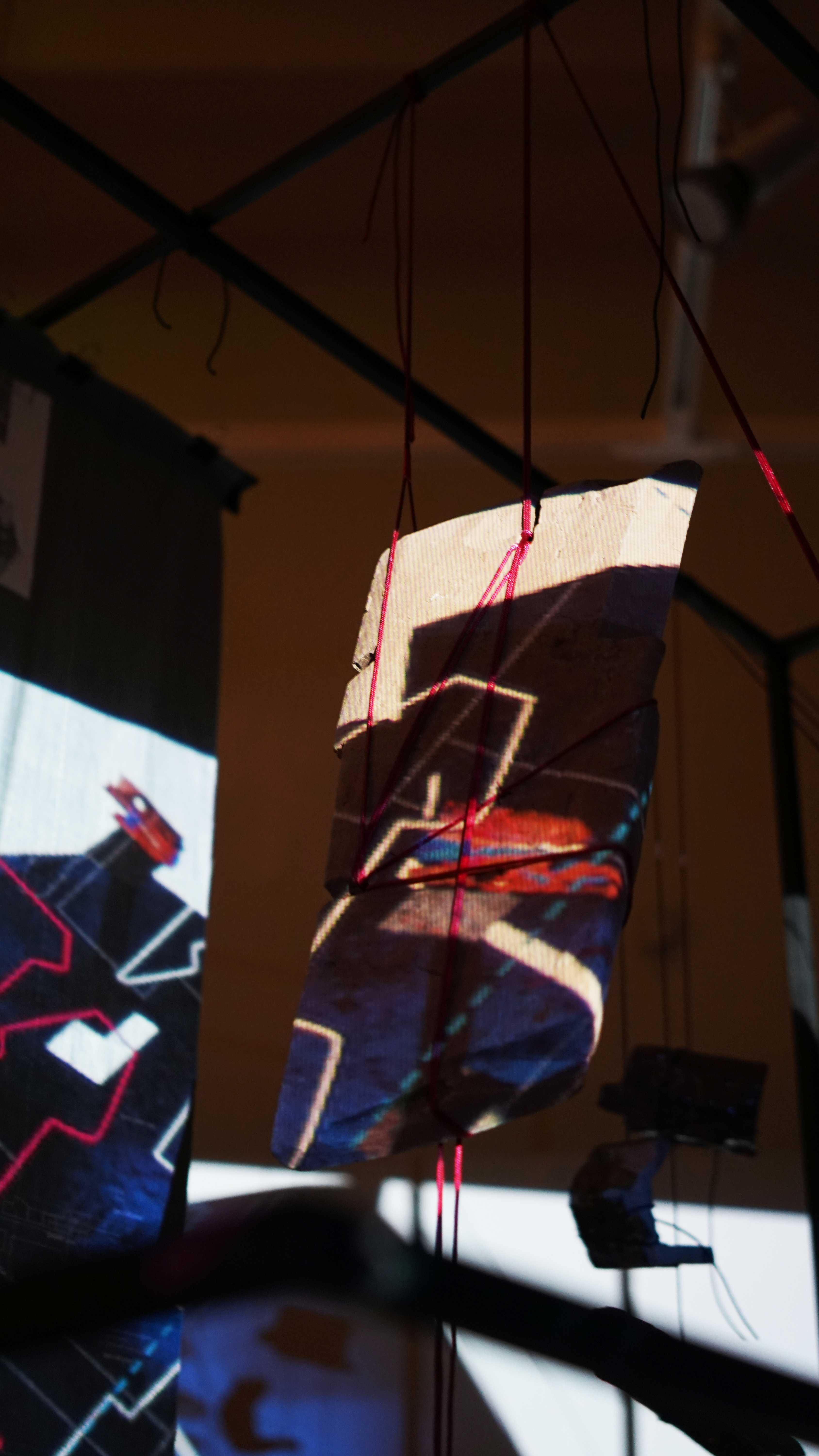

Above I made the claim that material practices, along with their diversified gestural figurations and associated bodily and cosmic consciousness – a process of re-appropriating image/xiang – might challenge and break away from the bad infinity of mono-technologism and serve to open towards a bifurcation of the future. The design-research project draws on fragments of digital scan data and resituates them within a place of installations and inscriptions. In doing so, the place of the project is conceived as a testing ground for re-appropriation. The clay characters serve as tools to defamiliarize and reterritorialize the everyday objects in My Room: an unmade bed; a pile of books; a curtain hastily drawn away; an enclosed wardrobe; a chair, ready to be sat on; a slightly open door; a tangled mess of cables; a bird’s cage, covered in dust; a poster, hanging; a desk; a cup, half filled…This process, restoring Chinese writing as cosmic patterns and as a bodily practice, further opens up to a gestural and tactile plurality and difference: the suspension of clay pieces by threads; the gesture of holding clay with an armature; the scoring of scripted lines; the registry of shadows; the play of absorption, saturation, and reflection of light due to material differences; and a wide range of markings and inscriptions on clay, steel, fabric, and timber surfaces. The place of installation acts as a provocation, disturbing the rigid relationship between the face and the hand in the digital reading system by encouraging a spontaneous and peripatetic mode of reading in space. The clay characters – forming a new architectural text – can thus be “read” across various distances and from multiple vantage points and angles of viewing, creating a subtle poetic inter-play of presence-absence.

06. Toward a Scripto-technics. Installation with projections, Matthew Architecture Gallery, Edinburgh. January 2025.

The notion of place is originally understood in Greek philosophy as either “a vacant space between bodies, permitting their displacement” or as “interstitial space mingled with things.”[45] It is thus interpreted through a relation between void and bodies, between there is and there is not, which leads to the ontological question of Being and, subsequently, the question of Meaning. In contrast, within the tradition of Chinese thought, place was never developed as an object of ontological enquiry, a system of knowledge. Instead, it is conceived through an embodied, readiness-to-hand process of making, experiencing, and immersing in the world of practical and technical activities.[46] Taking a clay vessel as an example, the Laozi states:

埏埴以為器,

當其無,

有器之用。

Mould clay into a vessel;

From its not-being (in the vessel’s hollow)

Arises the utility of the vessel.[47]

“The Laozi does not understand the experience of fashioning a vessel from earth either in terms of the uncovering of Being or in terms of the breaking and entering carried out by Meaning,”[48] remarks Jullien,

“…the vessel is left with its pure readiness-to-hand…In that respect, the vessel does not represent anything…in becoming hollow on the bottom and opening wide at its lip, the vessel can now serve as a vessel.”[49]

Stripped of its ontological reflections and detached from the system of representation, Laozi’s image of a clay vessel – as a technical tool – is conceived purely through its readiness-to-hand, made possible by its being hollowed and emptied – that is, by being enveloped in a place of non-being, of nothingness. In a similar vein, Hui develops a logic of place that presupposes nothingness as its enveloping ground.[50] It is in the place of nothingness that the ego, the cause of a subject/object opposition, is dissolved, and the subject is enveloped and transformed from a knowing subject into an emplaced subject.[51] This holds urgent relevance for us today. Rather than taking technology as the totality of ground, through forming a reciprocal relationship with the enveloping ground of unknowing, this paper calls for understanding the act of resituating of technology as a primary task of design research thinking and practice today. This resituating of technology necessarily entails a cosmotechnical thinking that suggests a process of discovering new frameworks with new values, some of which have been tested in this project through cosmotechnical practices of re-appropriating the image/xiang with clay.[52]

Published 10th November, 2025.

Notes

[01] Martin Heidegger, “The End of Philosophy and the Task of Thinking,” in On Time and Being, trans. Joan Stambaugh (New York: Harper & Row, 1972), 55.

[02] Yuk Hui, “Cosmotechnics as Cosmopolitics” E-flux Journal 86 (November 2017), accessed 15th June 2025. https://www.e-flux.com/journal/86/161887/cosmotechnics-as-cosmopolitics/.

[03] Heidegger, “The End of Philosophy,” 65-67.

[04] Yuk Hui, Art and Cosmotechnics (University of Minnesota Press, 2021), 143.

[05] Hui, Art and Cosmotechnics, 149-50.

[06] Hui, Art and Cosmotechnics, 272.

[07] Yuk Hui, The Question Concerning Technology in China: An Essay in Cosmotechnics (Falmouth, UK: Urbanomic, 2016), 61.

[08] The project of modernization of the Chinese writing system, tracible to the year 1900, was considered a matter of life and death, and a central weapon for ensuring national survival during a time of war and turmoil. One of the key advocates at the time was the linguist Wang Zhao (王照, 1859-1933) who single handedly took the task of saving China with literacy by preparing a thin document entitled Mandarin Combined Tone Alphabet in order to unify the nation’s tongue through Latinization. For a detailed study on the key stages of Chinese script’s modernization, see Jing Tsu, Kingdom of Characters: The Language Revolution That Made China Modern (New York: Riverhead Books, 2022).

[09] Hui, The Question Concerning Technology in China, 151.

[10] Yuk Hui, "One Hundred Years of Crisis." E-flux Journal 108 (April 2020), accessed 15th June 2025. https://www.e-flux.com/journal/108/326411/one-hundred-years-of-crisis/.

[11] Hui, "One Hundred Years of Crisis."

[12] Hui, "One Hundred Years of Crisis."

[13] Yuk Hui, On the Existence of Digital Objects, Electronic Mediations 48, (Minneapolis: the University of Minnesota Press, 2016), 146-57.

[14] Hui, On the Existence of Digital Objects, 157.

[15] Hui, The Question Concerning Technology in China, 61.

[16] Hui, The Question Concerning Technology in China, 151.

[17] This paper on scripto-technics is developed from my Architecture PhD by Design thesis, The Chang’an Rhapsody: Towards a Graphmatology of Writing (2025), which focuses on the image/xiang in the Chinese aesthetic tradition. A chapter entitled Terracotta Masks explores a cosmotechnics of clay through threefold technics: scripto-, pyro-, and mnemo-technics.

[18] Hui, The Question Concerning Technology in China, 151.

[19] Hui, The Question Concerning Technology in China, 47.

[20] Hui, The Question Concerning Technology in China, 110.

[21] Tsu, Kingdom of Characters, 242-70.

[22] Yuk Hui, "Writing and Cosmotechnics," Derrida Today 13, no. 1 (2020): 27, https://doi.org/10.3366/drt.2020.0217.

[23] Hui, Art and Cosmotechnics, 175.

[24] Hui, Art and Cosmotechnics, 152. The translation is with Yuk Hui’s modification based on Lao Tzu, Tao Te Ching, trans. D.C. Lau (Hong Kong: Chinese University of Hong Kong, 2001), chapter 21.

[25] Hui, Art and Cosmotechnics, 243.

[26] Yuk Hui notes that Chinese characters are commonly called “ideograms”, but he prefers to call them “pictograms” since a character is not an “idea” in the Platonic sense, but rather pictorial. See: Hui, "Writing and Cosmotechnics," 26.

[27] The six key techniques of constructing characters are: pictograms, indicatives, phono-semantic compounds, associative compounds, derivative cognates, phonetic loan characters (象形,指事,形聲,會意,轉注,假借). See: Hui, "Writing and Cosmotechnics," 26.

[28] Hui, "Writing and Cosmotechnics," 26.

[29] Hui, "Writing and Cosmotechnics," 28-29.

[30] The legend Cang Jie (倉頡), is known as the scribe of Yellow Emperor who invented writing by observing the marks left on the ground by birds and other animals. And Xi Zhong (奚仲) is known as the inventor of the chariot. Françoise Bottéro, "Cang Jie and the Invention of Writing: Reflections on the Elaboration of a Legend," Centre de recherches linguistiques sur l'Asie orientale: 146.

[31] I would like to thank one of the peer reviewers for drawing my attention to the interesting contrast between the concept of trace in the West and in China through Pliny the Elder.

[32] François Jullien, The Great Image Has No Form, or On the Nonobject through Painting, trans. Jane Marie Todd (Chicago and London: University Of Chicago Press, 2012), 103.

[33] The story of how writing was invented based on “cosmic inscriptions” shows that it was not based on recorded speech but rather as observations of visual signs as traces of natural phenomena. It’s believed that early Chinese (500 BCE - 200 CE) do not operate with the idea of language, since writing and speech are not considered as two manifestations of a bigger entity called language. Writing is singled out as a uniquely significant means of “notation, memory, and communication.” In fact, observes Jane Geaney, “if by “language” we mean a single phenomenon that includes speech, names, and writing – that is, a structure or an abstraction that is manifest in speech and writing – then early Chinese writers were not talking about “language” even implicitly.” In this sense, differing from language of the West, Chinese language is a “bodily practice.” Jane Geaney, Language as bodily practice in early China: a Chinese grammatology, SUNY series in Chinese philosophy and culture, (New York: State University of New York Press 2018), xxiv.

[34] The story-telling and narrative dimension of translating the LiDAR scan patterns into scripts is not the focus of this paper; however, it has been explored in a previously published paper entitled “[with]Drawing-Room: Surveying the Uncertain, the Estranged, the Monstrous” under the pseudonym Yuman Zeon 宇文錫安, in Idea Journal 20, no.1 (2023): Uncertain Interiors, 136-149. https://doi.org/10.37113/ij.v20i01.

[35] William G. Boltz, "The Invention of Writing in China," Oriens Extremus 42 (2000): 1-17. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24053703.

[36] It is likely that the signs are used to mark the ownership of the pottery. Paola Demattè, The Origins of Chinese Writing (New York: Oxford University Press, 2022), 116-23.

[37] Jullien, The Great Image Has No Form, 95.

[38] Jullien, The Great Image Has No Form, 91.

[39] Jullien, The Great Image Has No Form, 81-82.

[40] Jullien, The Great Image Has No Form, 100.

[41] Jullien, The Great Image Has No Form, 100.

[42] Jullien, The Great Image Has No Form, 60-61.

[43] Jullien, The Great Image Has No Form, 61.

[44] Jullien, The Great Image Has No Form, 62.

[45] Jullien, The Great Image Has No Form, 80.

[46] Jullien, The Great Image Has No Form, 80-81.

[47] Laozi, Dao De Jing, trans. Lin Yutang, Chapter 11, accessed 7th April, 2025, https://terebess.hu/english/tao/yutang.html#Kap11.

[48] Jullien, The Great Image Has No Form, 82.

[49] Jullien, The Great Image Has No Form, 82.

[50] Hui understands the place of nothingness through the notion of basho (place, 場所). Basho is developed by the Japanese philosopher Kitarō Nishida which allows him to explore the question of “a form without form” and “an voice without voice” in contrast to the development of form and being of the West. See: Hui, Art and Cosmotechnics, 256-58.

[51] Hui, Art and Cosmotechnics, 262.

[52] Hui, Art and Cosmotechnics, 262.

Figures

Banner.

Toward a Scripto-technics. Installation with projections, Matthew Architecture Gallery, Edinburgh. January 2025. Leo Xian.

01.

Oracle Bone Scripts, Leo Xian, 2024.

02.

LiDAR Scan of My Room. Digital Drawing, Leo Xian, 2024.

03.

The process of inventing new Chinese characters based on LiDAR scanning patterns of My Room. The scanning patterns are scripted as characters according to the Chinese writerGao Xingjian’s play Between Life and Death (1991). Digital drawing, Leo Xian, 2024.

04.

Moulding, sculpting, sketching, and naming with terrocotta clay (unfired). Leo Xian, 2024.

05.

Sketching on the terracotta clay pieces. Leo Xian, 2024.

06.

Toward a Scripto-technics. Installation with projections, Matthew Architecture Gallery, Edinburgh. January 2025. Leo Xian.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the editor, Chris French, for his care, patience, and insightful suggestions, which have been invaluable in developing this work. I am also grateful to the two anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful reflections and comments. My colleague at the University of Edinburgh, Paul Pattinson, has been an important influence, and I am indebted to his PhD research on technicity and LiDAR scanning in India, which has inspired my own thinking. I also wish to thank my PhD supervisors, Dr. Dorian Wiszniewski and Adrian Hawker, whose guidance have shaped the dissertation chapter on which this piece is based. Finally, I would like to acknowledge those involved in the MSc Architectural and Urban Design programme, with whom I have the pleasure of co-teaching, for continually inspiring a critical and speculative engagement with the notion of technics in relation to modern technology.

I would like to thank the editor, Chris French, for his care, patience, and insightful suggestions, which have been invaluable in developing this work. I am also grateful to the two anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful reflections and comments. My colleague at the University of Edinburgh, Paul Pattinson, has been an important influence, and I am indebted to his PhD research on technicity and LiDAR scanning in India, which has inspired my own thinking. I also wish to thank my PhD supervisors, Dr. Dorian Wiszniewski and Adrian Hawker, whose guidance have shaped the dissertation chapter on which this piece is based. Finally, I would like to acknowledge those involved in the MSc Architectural and Urban Design programme, with whom I have the pleasure of co-teaching, for continually inspiring a critical and speculative engagement with the notion of technics in relation to modern technology.

https://doi.org/10.2218/rkfpbc31