Cracks, Chairs, and Child-Players: Encounters with the Ordinary, from Wajirō Kon to Atelier Bow-Wow

Nergis Kalli

“Now, whatever you might think,

The gods dwell in the streets.”[01]

Terunobu Fujimori

Foregrounding Ordinary Encounters: A Café in Newcastle

“This is a very small café, with just six tables inside and two outside. The two owners are shouting at each other in Italian behind the tiny counter. In the corner, a family with two kids is deep in conversation about strawberries as they share a slice of strawberry cake. Right in front of me, a young woman is chatting with a man who has just taken the table next to hers. Some people wait patiently to order. Not long after, the family leaves, and another man (who turns out to be the young woman’s boyfriend) arrives and joins the queue to order.Outside, an elderly gentleman chats with a younger man who could easily pass for his younger self, likely his son. It is cold in Newcastle today but, as some small consolation, Newcastle is always cold, so there is no need to wait for summer to sit outside. Sharing this mindset, another couple occupies the second outdoor table with their backs to the café’s glass frontage. A few minutes later, an elderly couple borrows two chairs from their table and settles in comfortably with coffees in hand, not needing a table.

From outside the café one can watch the various people strolling down the main thoroughfare that links the Quayside to Grey's Monument, the de facto public square of Newcastle, created not by design but through a natural convergence of pedestrians, shops and the monument itself. Charles Grey’s statue perches atop a Doric column overlooking the River Tyne; below, the broad stepped base located between two busy metro exits has become a stage for political activists, musicians and social groups.

While I was transcribing this scene, something strange happened. Our young couple had been chatting with the young man at the adjacent table. The boyfriend subtly shifted his chair, so slightly that it was barely noticeable and yet enough to ensure that the couple could only see one another. Now excluded, the young man put on headphones and disappeared into his book. He sits alone at a table for four, which tends to draw the owners’ intense glares during busy times like this.

As a regular, I've claimed my favourite spot by the window. To my right, there's no seat, just a bench that runs along the wall, which is far more comfortable than the chairs scattered around the café. The table is small, but it fits my laptop and coffee cup snugly side by side. From here I enjoy a view of Grey Street and start writing this wandering text.”

The café, like the many other small extensions of home that we frequently inhabit for brief intervals, is a space where there is no architecture to discuss in the conventional sense, yet it operates in a profoundly humane and spatially meaningful way. Although I am usually less observant of my surroundings, and while the space has grown almost invisible through familiarity, this visit focused my attention on small details: the number of tables, age of customers, expressions of the owners, and how moving a chair can change the space, or how a simple arrangement of furniture can contribute to the public space around Grey's Monument by becoming part of the same urban assemblage as the landmark itself.[02]

This brief engagement with the ordinary was inspired, albeit in a simplified way, by several figures in the Japanese art and architecture scene: artist and architectural scholar Wajirō Kon; the architectural historian Terunobu Fujimori and artist Genpei Akasegawa; and the founding partners of Atelier Bow-Wow, Yoshiharu Tsukamoto and Momoyo Kaijima. What ties their work together is a particular approach to fieldwork referred to as urban survey in Japan. These influential figures reinterpreted the urban survey as a tool that extracted meaning from the mundane by cultivating a deliberately absurd and witty sensibility. From cracks in cups, to Tokyo’s manhole cover patterns, to pet-like small buildings, seemingly trivial details open unexpected paths to freedom in thought and creative expression.

The essay explores the narratives of these practitioners through their own words and works and examines how field documentation and drawing shape and communicate creative discoveries. It concludes with a reflection through Gilles Deleuze which reframes their distinctive way of seeing as a gaze grounded in a non-judgemental engagement with the city. I believe this “conceptualised gaze,” shared by Kon, Fujimori and Atelier Bow-Wow, can be adopted to read, inhabit and learn from the ordinary urban realms that we traverse.

Wajirō Kon

Wajirō Kon (1888–1973) studied design at Tokyo School of Fine Arts and later taught architecture at Waseda University from 1920 to 1959. He conducted fieldwork studying minka (traditional folk dwellings) under the mentorship of Kunio Yanagita, widely regarded as the father of Japanese folklore studies. This immersion in vernacular culture influenced Kon’s observational approach to everyday life and guided his later studies. In 1923, after the Great Kantō Earthquake and subsequent fires devastated Tokyo, Kon's focus shifted from rural to urban settings. He began documenting how survivors ingeniously built temporary shelters with salvaged materials.[03] Reflecting on their resourcefulness, he wrote:“The houses made from burned, corrugated iron scrap are a deep, chalky red. A man who managed to procure a can of coal tar went about applying it to the walls of the houses and to their strange, monstrous roofs until he had used up every last drop. A can’s worth of markings was the houses’ only decoration. These black, red and blue houses with their roofs – sometimes light, sometimes heavy, often peculiar are quite remarkable. Architects should take note of people’s ingenuity.”[04]

Moved by the resilience of survivors, Kon co-founded the “Barrack Decoration Society” with designer Kenkichi Yoshida, a fellow graduate of Tokyo Fine Arts University, and his own students from Waseda University. The group documented the construction of barracks and the surrounding daily life through sketches, notes and photographs.[05] Their work soon expanded to decorating shelters and temporary shops as a simple yet meaningful gesture of aesthetic care that brought comfort to those displaced. These efforts soon attracted criticism, especially from the young modernists in the Bunriha Kenchiku Kai (Secessionist Architectural Group), who dismissed ornamentation as a regressive departure from modernist ideals. In response, Kon advocated for decoration “not as something attached to objects, but as a playful technique of lines and colours directly expressing people’s personalities.”[06] Although generally courteous, Kon accompanied his explanation with an acerbic analogy aimed at his critics:

“This group seems to believe that music is a series of unaccompanied sounds and that architecture is an arrangement of unaccompanied objects in space. I do not know what kind of opinions they have about a “barrack house” which is a work constructed in extremely difficult economic conditions.”[07]

This was not going to be Kon’s first clash with radical modernists. He opposed the functionalist view that prioritized standardisation as he believed that city planning should be grounded in a thorough understanding of everyday life, rather than abstract principles.[08] This conflict over decoration, however, was intense enough to draw Kon away from the architectural scene briefly.[09] By 1925, he had turned his attention to signs of Japan's rapid modernization in Ginza, the centre of cosmopolitan flair. Working with Yoshida and the members of the Barrack Decoration Society, Kon documented a combination of phenomena, ranging from urban-scale surveys down to cracks in teacups.

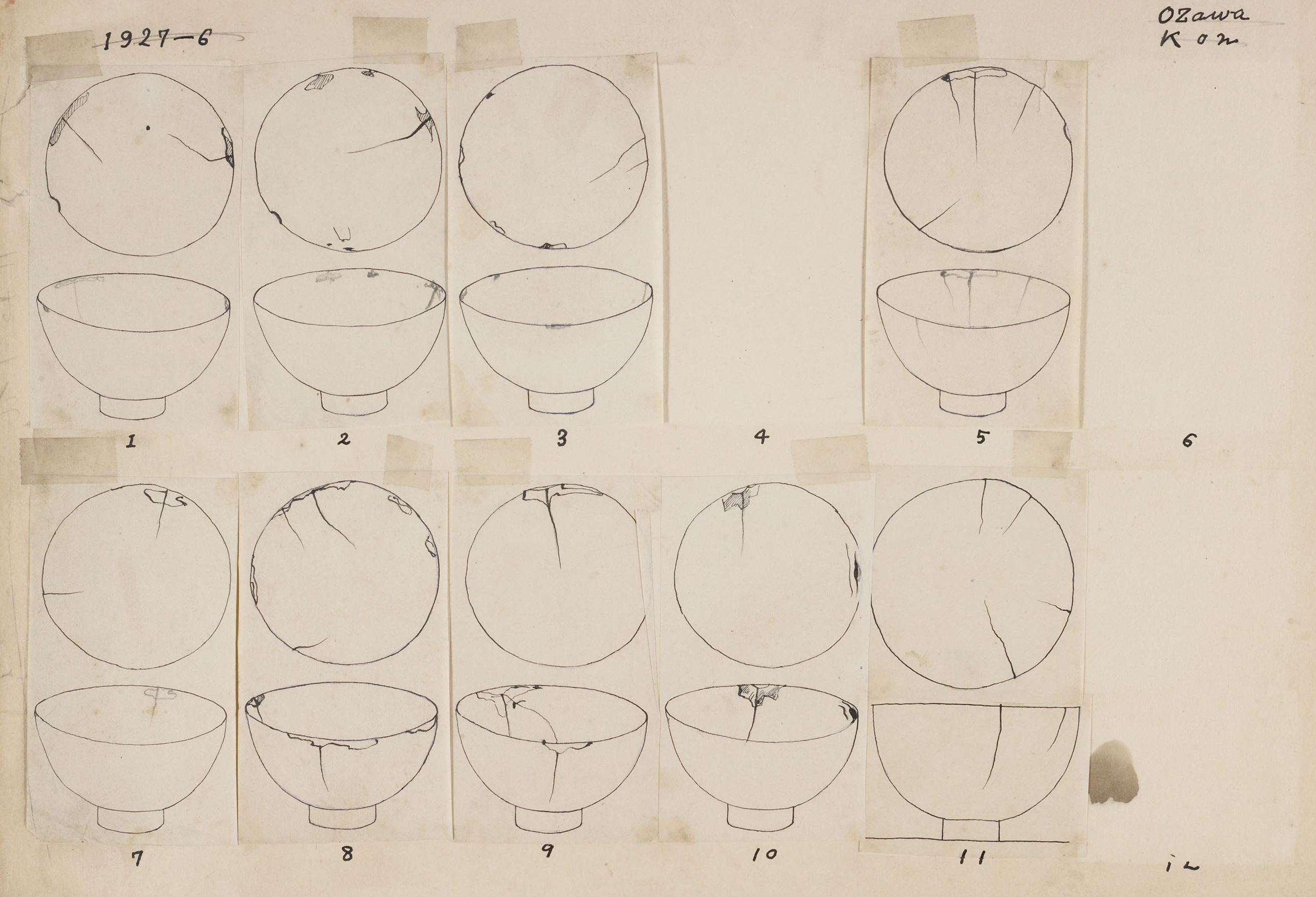

01. Wajirō Kon and Shōzō Ozawa, “Cracks in Bowls at an Eating House,” 1927. The drawing records every crack in a set of bowls.

Around this time, Kon also formalised his thinking under the title of “modernology.”[10] The Japanese term he coined for modernology, kōgengaku (考現学), illustrates his idea through a linguistic twist. Kon replaced the “ancient” (古, ko) in archaeology (kōkogaku, 考古学) with “present” (現, gen) to create a new field: “the science of the present.” Like an archaeologist, Kon pursued discovery by excavation, but an excavation of contemporary life. For Kon, modernology was an archaeology of the now.[11]

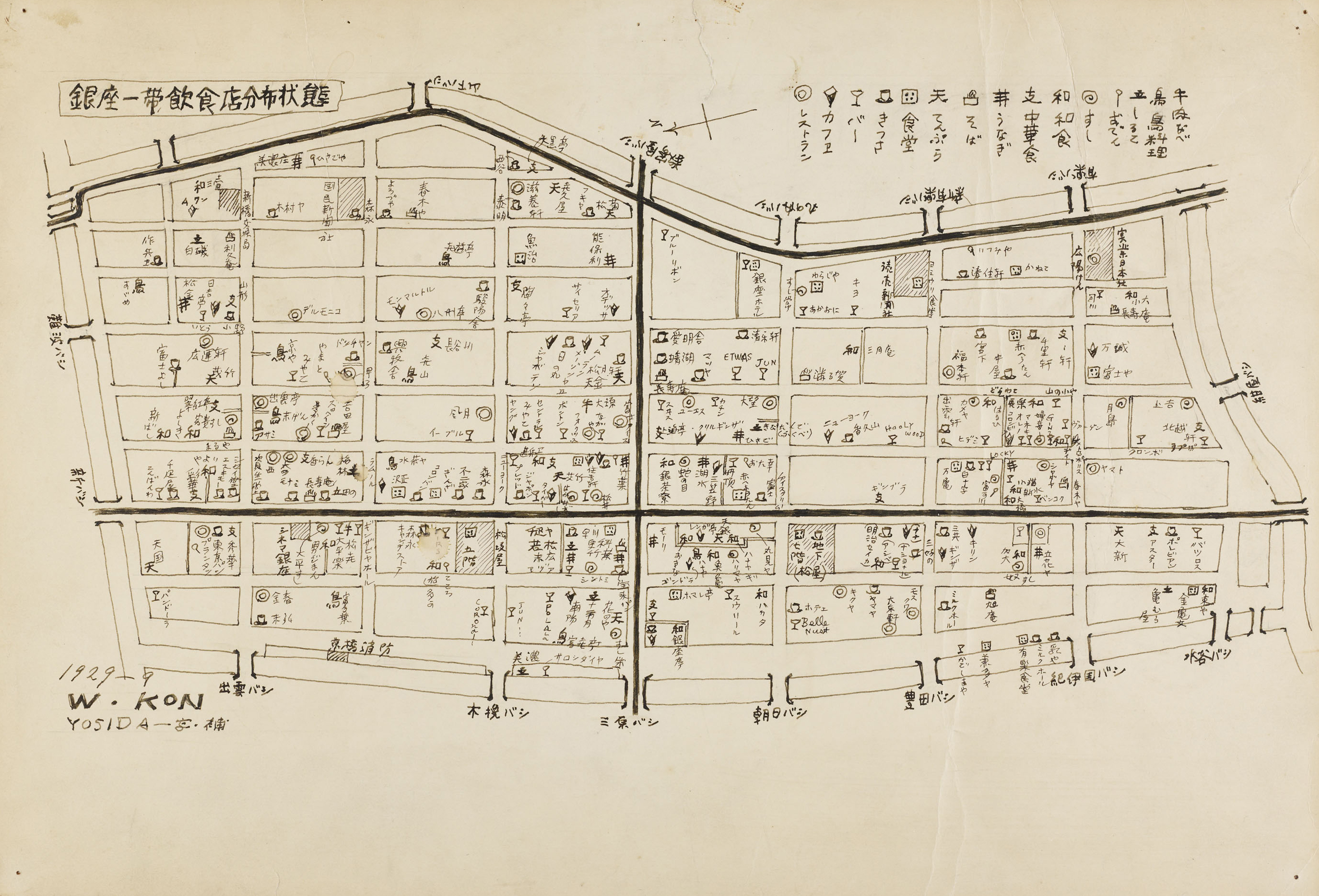

02. Wajirō Kon and Kenkichi Yoshida, “Map of Restaurants and Drinking Establishments in Ginza,” 1929. A legend at the top right assigns icons to a detailed list of establishments: restaurants, cafés, bars, kissaten, tempura shops, soba stands, unagi don vendors, Chinese eateries, sushi bars, oden stalls, poultry restaurants, and beef hot-pot venues. Each block contains matching symbols and handwritten shop names. The drawing expands Kon's survey from individual observations to the neighborhood.

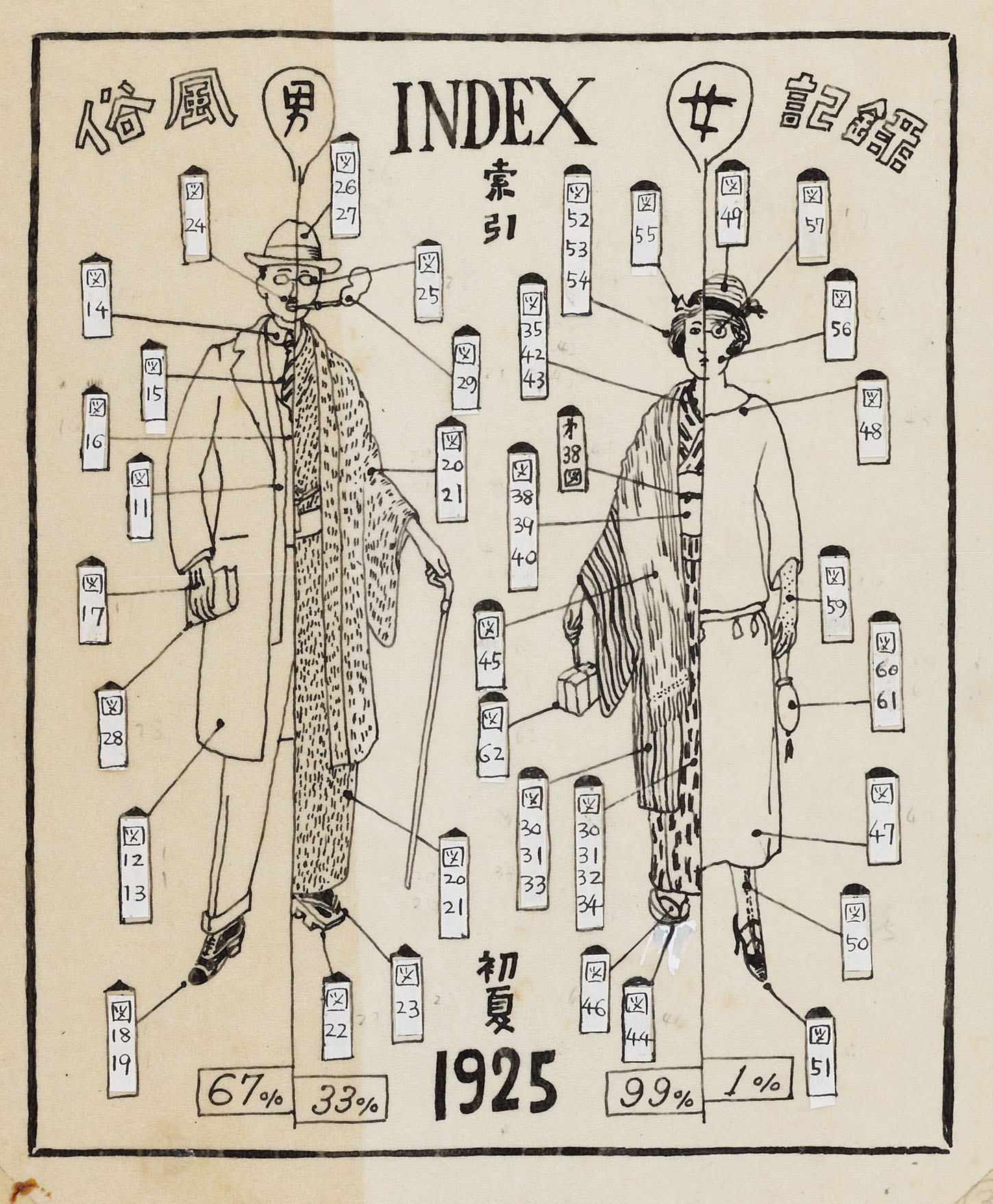

Within that “now,” one can find him illustrating changing fashion trends in Ginza by depicting a man and a woman split into modern and traditional attire, each part numbered to identify garments, accessories and hairstyles, with percentages that compare clothing preferences of each gender. In another case, working with Yoshida, he mapped and categorised all of Ginza’s dining establishments, how they clustered and where venues offering Western food and drink were beginning to concentrate with a detailed legend. The site of these observations soon expanded beyond Ginza, as did what was documented. As Kon wrote:

“We must study, for example, different types of people in various circumstances, such as their speed and form while walking, their manner of repose and how they seat themselves, the mannerisms reflected in the minutest details of their bodies, the patterns adopted by pedestrians on the street and the placement of street stalls and shops in response to them, people promenading at parks, the different kinds of queues people form, scenes at rallies and meeting halls, the comings-and-goings of foremen and the activity of construction workers on the street … [T]he effectiveness of our work is based on the particularity of our method, as well as our interest in objects that researchers in other sciences miss or cannot address.”[12]

One object that researchers in other sciences might have missed was the cracks in teacups at an eatery, which Kon examined from multiple angles like an orthographic projection of a scientific specimen. Though focusing on these cracks may seem absurd, they are more than a humorous marker of Kon’s radical eye; they also signal the humble state of the eatery itself (its ownership undisclosed yet assumed to be Waseda University’s cafeteria)[13] and show that everything observed, no matter how trivial, merits recording, because such details can reveal the social and material realities of a particular time and place.

03. Wajirō Kon, “Ginza Fashion Survey Index” 1925. Kon’s split figures compare Western and Japanese dress; numbered tags label each item in the index, and ratios beneath their feet show how Ginza was tilting toward Western styles.

To record and convey these observations, Kon relied on drawing as his primary tool, with a personal and subtly witty style informed by avant-garde influences and his training at Tokyo Fine Arts University. His works often feel conversational, incorporating notes, arrows, speech bubbles, dates, measurements, prices, and other annotations, all of which naturally complemented the minute details within his subject matter, how interactions between people and objects reveal the shifting social ethos and how these changes create urban space.[14]

Street Observation Society (ROJO)

In the 1974, following Kon’s legacy, Terunobu Fujimori established the “Architectural Detective Agency” with architect Takeyoshi Hori, a fellow graduate student at the University of Tokyo. The name of the group was inspired by Tarō Hirai (better known by his pen name Edogawa Ranpo) and his Boy Detectives Club

stories, themselves modelled on the Baker Street Irregulars from Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories. With cameras and sketchbooks in hand, the “detectives” roamed Tokyo documenting buildings that stood out for their historical and stylistic peculiarities, some of which were under the threat of demolition and not yet regarded as part of Japanese architectural history.[15] The research of the agency soon expanded beyond Tokyo. The team documented and catalogued approximately 13,000 buildings with the assistance of local university faculty and students. Their goal of creating an archive to document structures at risk of being demolished and forgotten was eventually achieved.[16]At the same time, writer and avant-garde artist Genpei Akasegawa was working on a similar project. He developed his own practice of seeking out and cataloguing curious objects, originally coining the term “hyperart” to describe his search for defunct, useless yet aesthetically intriguing items abandoned on the streets or affixed to private property. As the work developed, Akasegawa determined that the term hyperart could not do justice to these objects, and proposed alternatives like “hermetifices,” “forgetifices,” “impolises.” In the end, he settled on “Thomasson,” inspired by Gary Thomasson, an American baseball player whose high-profile transfer to Japan's Yomiuri Giants failed to meet the expectations of Japanese fanfare. Akasegawa saw him as a beautiful figure sitting on the bench and yet serving no purpose to the world. Thomasson, to him, was living hyperart, and thus he began calling every odd architectural remnant he found a Thomasson, which has been referenced heavily in Japanese art scene thereafter.[17]

In 1986, Fujimori and Akasegawa crossed paths through their mutual friend, editor Tetsuo Matsuda. Along with illustrator Shinbō Minami, modern manga artist, Edo-era customs researcher Hinako Sugiura, and writer Jōji Hayashi, they came together to establish the Street Observation Society, officially known as Rojō Kansatsu Gakkai (ROJO). Hayashi, who spent over a decade in Europe and Japan photographing manhole covers, was a particularly distinctive member. Architectural historian Thomas Daniell, writing about the group, notes that other members jokingly referred to Hayashi as “a child, an alien, or a deity,” descriptions that carry much admiration.[18] Their official launch was as lively as the members themselves. On June 10, 1986, members in morning coats met on the steps of the University Club in downtown Tokyo, unfurled a banner and announced their inauguration to the press, a scene Akasegawa later likened to the formation of a new cabinet.[19]

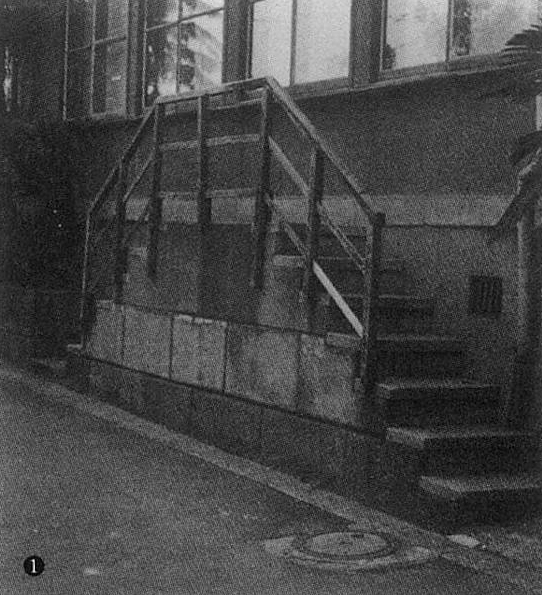

This theatrical gesture was an early sign of ROJO's humorous approach to exploring the city. The group would gather at specific locations to observe and catalogue objects in the street that seemed to have no economic or cultural value, such as abandoned fire hydrants, or an old television set converted into a chicken coop. Stairs to nowhere, which had no purpose beyond allowing people to ascend and descend without leading to any particular view or entrance, were among the earliest documented examples. The first instance was recorded in 1972 in Yotsuya, Tokyo, well before the group officially formed, and the phenomenon later evolved into its own category of “pure stairs.”[20]

04. Takeshi Suzuki, “Pure Stair” case studies, from a spread in Rojō Kansatsugaku Nyūmon (Street Observation Studies Primer), Chikuma Shobō, 1986. Three street photographs show ROJO’s “pure stairs”: one steps up then down with nowhere to enter, one stops underneath an eaves, and one runs straight into a blank wall.

Spotting “pure stairs” or similar anomalies hidden in the urban landscape requires thorough preparation even if the whimsical nature of the found objects might suggest otherwise; members would first attend a lecture by Fujimori about the area in the morning, then conduct on-site observations in pre-assigned zones, and typically meet in the evening to discuss their findings until late at night.[21] They advised fellow observers to bring cameras, tape recorders, measuring tapes, maps, notebooks, various pens and pencils, and even candy and biscuits, equipment totalling more than three kilograms, which member Hayashi listed and illustrated in a single drawing. The illustration was later published in the Rojō Kansatsugaku Nyūmon (Street Observation Studies Primer) with other illustrations, photographs of Thomassons, maps and methodological notes that recall Kon’s emphasis on noticing what already exists in the present.

05. Jōji Hayashi, “Tools for Street-Walking,” in Rojō Kansatsugaku Nyūmon (Street Observation Studies Primer), Chikuma Shobō, 1986. Hayashi inventories the ROJO field kit in obsessive yet entertaining detail, from the camera to the alphabet cookies and Calmin mints (all weighed). The illustration also comes with brief practical notes, such as which shoes are ideal for city walking in terms of weight.

The focus on what is out there also influenced ROJO’s perspective on the city, especially through Fujimori’s influence. In the late 1980s, urban studies on Tokyo often revolved around revealing the hidden layers of the city by tracing the history back to the Edo period.[22] These layers could only be perceived through indirect signs at certain locations as Tokyo’s urban landscape had been in a constant flux of rapid building turnover driven by high land prices. Fujimori, unsurprisingly, rejected this retrospective reading. Aligning himself with the “Object School,” he drew a clear line between ROJO and what he referred to as the “Space School”.

“We don’t want any antagonism ... The Space School conceals in its heart the desire to return to a harmonious integrity ... The devastating techniques of the Space School, such as ‘reading a city’ or ‘reading a code,’ are methodologically similar to semiotics. And what becomes visible as a result of these readings is the order of the good old days. The Edo waterfront was vibrant, the back alleys of the old downtown neighbourhoods were wonderful—that kind of thing … However, alas, our eyeballs are not like that. When walking by a canal, rather than the floating spaces, our eyes are first caught by the broken dolls, scraps of wood, and bottles floating on the surface of the water. Shamefully, we are more sensitive towards objects than spaces... Because we are preoccupied by objects, each individual object leaves an interesting impression as it passes across our eyes, but no trace of an overall order remains on our retinas.”[23]

Rejecting the notion of the city as an entity bound by predefined values, Fujimori found refuge in the object. An object is more than an eccentricity encountered on the street, it signals events that happened in the past and have potential to happen in the future. Since events can bypass ready-made and sometimes rigid frameworks – like historical harmony or imposed order – the voice of the site or city can be heard more directly through them. Behind Fujimori's fascination with the object is this direct connection to the event that can dissolve preconceptions and awaken the freedom of thought that ROJO discovered on the street.

Atelier Bow-Wow

Atelier Bow-Wow, established in Tokyo in 1992 by Yoshiharu Tsukamoto and Momoyo Kaijima, is one of Japan’s most internationally recognized architectural practices. Despite their current prominence, Tsukamoto and Kaijima, both born in the late 1960s, began their careers during a difficult period after Japan’s economic bubble burst in 1991. Unable to maintain independent practices in these uneasy economic conditions, many architects formed collaborative units. Architectural historian Tarō Igarashi situates Atelier Bow-Wow within this context as part of the “post-bubble generation” that focused on urban fieldwork during a period of limited opportunities. This generation, particularly in Tokyo, found unexpected creativity in ordinary places by examining “awkward slits” of urban life.[24]

Their concept of dame, meaning “no good,” “useless,” or “broken,” in Japanese, shows Tsukamoto and Kaijima’s focus on the ordinary, from tiny noodle shops and ubiquitous vending machines to expressways towering like concrete giants over the city, all considered architectural elements worthy of study. Not falling far from hyperart, dame becomes a tool for understanding Tokyo by dissecting its fragments.[25] This approach does not dismiss what might seem unconventional by Western standards but instead investigates what can be considered standard within the peculiar urban fabric of the city. They write:

“In 1991, we discovered a narrow spaghetti shop wrenched into the space under a baseball batting centre hanging from a steep incline. Neither spaghetti shop nor batting centre are unusual in Tokyo, but the packaging of the two together cannot be explained rationally…This building simultaneously invited a feeling of suspicion that it was pure nonsense, and expectation in its joyful and wilful energy. But we also felt how ‘very Tokyo’ are those buildings which accompany this ambiguous feeling. Having been struck by how interesting they are, we set out to photograph them, just as though we were visiting a foreign city for the first time. This is the beginning of ‘Made in Tokyo’, a survey of nameless and strange buildings of this city.”[26]

Made in Tokyo, as a collection of the dame cases, was designed as a guidebook in response to the popular guidebooks of the time that showcased contemporary architectural highlights of the city. In place of architectural masterpieces, Made in Tokyo features a pachinko parlour resembling Notre Dame Cathedral. The bustling parlour at the centre is surrounded by two neighbouring buildings (the towers of the cathedral) with multiple money lending businesses spread across several floors, creating a cycle in which visitors can gamble in the parlour and turn to the these offices for loans, caught in an endless loop of losing and borrowing money.[27] Their second publication, following Made in Tokyo, focuses exclusively on a single typology: “pet architecture,” buildings that crop up on fragmented lots, typically as a result of roadway expansions or the geometric misalignments caused by land divisions. The concept also refers to smallness, evoking the size and charm of pets, while subtly playing off the earlier term “rabbit hutches,” originating from a European Commission report dismissing the relatively small size of Japanese houses.[28] Rather than ignoring this old critique, they play with it by cataloguing over seventy examples of pet architecture across Tokyo.[29]

But how does one notice such phenomena? The parlour had been there for some time, what lens allows one to see it anew, and liken it to Notre Dame? One needs to search for the dame, attuned to their surroundings and ready to notice the cathedral, the impossibly tiny buildings crammed into unlikely spaces or surprising combinations of functions. In this sense, their approach is consistent with Kon and ROJO. Fujimori reflects on this lineage, stating:

“The young generation of architects, led by Tsukamoto and Kaijima, was expressing interest in a domain that architecture had always ignored. The thing that surprised me most was that Atelier Bow-Wow had not inherited the ROJO’s gaze as is. I was convinced that using this gaze to create things was out of the question, but here Atelier Bow-Wow was, creating. I was delighted. This gaze, which was transmitted from Wajirō Kon to ROJO, then down to Tsukamoto and Kaijima, is probably most evident in Atelier Bow-Wow’s yatai (portable kiosk) designs, titled Furnicycle and White Limousine Yatai. If Wajirō Kon had seen these works, his face would have crinkled up in joy like a baby monkey’s, and he might have returned to the world of architecture.”[30]

While adding a creative dimension to the lineage, Atelier Bow-Wow’s communication style contrasts with that of Kon and ROJO members, who often used hand-drawn sketches to convey stories. Both Made in Tokyo and Pet Architecture Guide Book were published as catalogues with small maps, photographs, brief descriptions and axonometric drawings of each building. Atelier Bow-Wow employed mechanical lines in their perspective drawings, which in a sense adheres to conventional architectural drawing practices, focusing more narrowly on the objects of discovery, their form, location, and function. Their technical style aligns with the emphasis on the formal qualities of buildings rather than subjective experiences. In other words, the lineage takes a sharp architectural turn with Atelier Bow-Wow, both in their use of observations in design practice and in their means of representation.

The Gaze of The Child-Player

The lineage from Wajirō Kon to ROJO and Atelier Bow-Wow shows a shared interest in urban survey, with Kon’s recording of everyday life as “archaeology of the now” at a critical time of change for Japan; ROJO’s search for Thomassons which tell stories of events that had happened and that could potentially happen; and Atelier Bow-Wow’s documentation of dame that shows how Tokyo’s chaos is based on an order of its own kind. In their work one can sense commonalities that transcend the survey itself: a willingness to approach established narratives with incredulity, and a rebellious daring. These commonalities resemble the acts of Deleuze’s “child-player.” The child-player is a figure capable of winning the divine game introduced in Deleuze’s magnum opus Difference and Repetition.[31] Here, Deleuze draws on Nietzsche’s metamorphoses of the spirit: the camel, the lion, and the child.[32]

The camel bears the world’s burden alone in the desert; the weights of societal norms, moral codes and traditional values. Over time, exhausted and disillusioned under these heavy burdens, the camel begins to question them. At that moment, it transforms into a rebellious lion willing to venture through the wilderness, and desiring nothing more than freedom and lordship over its own domain. However, the lion soon confronts its greatest enemy: the dragon of “thou shalt.” Covered in golden scales, each gleaming with “the values of all things” and “all value [that] has already been created,” this mightiest beast declares, “There shall be no more ‘I will’.” The lion, forced to conform to these values, simply says “No.” Refusing to be tamed, the lion rejects imposed values and cries out, “I will,” as the first step to freedom and authority.The attitude of our figures, sometimes hidden by wit and whimsy, is similar to Nietzsche’s rebellious lion. The problem, however, is that even the lion’s power has its limits; it can reject imposed values and assert its will, but guided only by negation, the lion cannot create anything new. As Nietzsche points out, another transformation must take place:

“But tell me, my brothers, of what is the child capable that even the lion is not? Why must the preying lion still become a child?”[33]

According to Nietzsche, the child surpasses the lion because a child is free from burdens, inherited values and presuppositions. In this final metamorphosis, the spirit can create itself anew and affirm the life:

“The child is innocence and forgetting, a new beginning, a game, a wheel rolling out of itself, a first movement, a sacred yes-saying.”[34]

It is this affirmation that enables our figures’ attitude to flourish into a gaze fixed on actual life. This life is life as it is, including aspects that are minor and might be overlooked because they have become too familiar to notice, or aspects not considered worthy of attention in the first place, as they have already been filtered out by the imaginary layers of importance decided by the established narratives of the time. This poses no problem for Nietzsche’s child who knows nothing of the “thou shalt.”

Deleuze radicalises the child further, declaring “Children are Spinozists.”[35] Following Spinoza, Deleuze argues that things are defined not by their essential nature but by their capabilities – how they affect and are affected by others. A child’s perception, Deleuze suggests, is fundamentally Spinozist because children understand objects and bodies through their connections, movements and interactions within changing assemblages, rather than through fixed essences or symbolic meanings. Their endless “whys” and “hows” become a generative force that explore events, functions and relationships instead of static labels,[36] much like Fujimori's focus on objects and their inherent connections to events.

The child’s generative force, however, comes into being only after one moves beyond pre-established categories, precisely because these categories are predetermined. Such categories force any new knowledge to conform to existing frameworks; if something cannot connect with what is already known or already recognisable, it will simply fail to find a place. In a Deleuzian sense, this rigid framework – what Deleuze generally refers to as “the image of thought” – can only endlessly return “the same” in a repetitive loop. As a result, “the difference” cannot appear and nothing genuinely new can emerge.

Deleuze’s child-player, however, both free from negation and pre-established rules can bring about the return of difference. In the lineage described above such creative potential was recognised when Fujimori happily observed that their shared gaze evolved into creative practice through Atelier Bow-Wow’s work. However, I believe the lion turned into the child well before that point.

The change, I would argue, resides in the moment of discovery in relation to one’s “capacity to be affected” by observed phenomena, which began with Kon’s documentation of the post-earthquake barracks, where he discerned glimpses of humanity through “a can’s worth of markings” in the rubble. The very act of noticing and “excavating” the desire to beautify shelter at a time of extreme hardship is a creative gesture. Thus, long before Atelier Bow-Wow’s White Limousine Yatai, the lineage was creating simply by attending to the phenomena they documented.

What is it that allows such discovery to acquire a creative power? The child-players engage in what Deleuze describes as an “encounter” that compels thought:

“Something in the world forces us to think. This something is an object not of recognition but of a fundamental encounter. What is encountered may be Socrates, a temple or a demon. It may be grasped in a range of affective tones: wonder, love, hatred, suffering. In whichever tone, its primary characteristic is that it can only be sensed.”[37]

An encounter is a coming-into-contact with something that disrupts our habitual ways of thinking and perceiving something through a source that causes “violence” in thought. The source can be familiar or unfamiliar, ordinary or grand, as long as it provokes thought. An encounter can only occur where no order of importance is ascribed to things in advance, as what has already been deemed insignificant will hardly be noticed. This is why the child’s “sacred Yes,” as an affirmation of life in its immanent form, is needed.

With the “sacred Yes,” one ceases to be a thinking subject isolated within the mind and becomes more like a “self-rolling wheel,” bumping into Socrates, a temple, a demon, a crack in a teacup, a broken doll, or a noodle shop. These fundamental encounters only happen through direct engagement with an external world beyond our minds, where we interact with things that have the capacity to affect us. The urban survey practiced by those within the lineage created opportunities for such encounters in a literal external world where our figures were always in search of something. What they found, recorded, and categorised under various names originates from encounters of an inherently similar kind.

To arrive at these encounters, we took a rather long journey in which the lion’s attitude gives way to the curious and nonjudgmental gaze of a child. This observant gaze makes encounters possible, and some of these encounters lead to creative discoveries. At this point, a new event occurs and heralds yet another metamorphosis: the representation of discovery. Our child-players are quite consistent in articulating their discoveries through visuals such as drawings, maps and photographs. This is simply because much of what Kon, and later ROJO and Atelier Bow-Wow, investigated was visual, starting from dramatic changes in culture to subtle street anomalies and architectural oddities. Drawing is both the inevitable (due to the figures’ background in art and architecture) and most fitting way to record their subject matter. The consequence of this form or representation is that creative discoveries, once discovered, come to life again through the figures themselves. Even when documentation is the main goal, as in most cases of urban survey, a form of individuality radiates from the one who noticed the object as a singularity, extracted it from the world and re-presented it. This is because drawing transcends a mechanical copying of the world by betraying signs of how the observer experiences and re-enacts that world. This applies both to the imperfect and sincere hand drawings of Kon and ROJO, as well as to Atelier Bow-Wow’s axonometric representations. In all cases drawing achieves a phenomenological depth by recreating discoveries each time they are translated into a visual language that is as interpretative as it is factual; it both preserves the data (the “what” of the city) and demonstrates the observer’s own sense of wonder, humour, or criticism (the “how” of seeing) in the second moment of creativity after discovery: the recreation of creation.

Then there is us, the audience. Drawing, rather than completing a cycle, creates an infinite line of ongoing dialogue between the observer, the city, and the audience around the survey. Through this “recreation,” which might also continue to develop in the audience’s mind, the hidden becomes visible and some of the overlooked possibilities are actualised, while raising questions about potential new ones. In a café, where we observe a microcosm of urban life filled with trivial details in the process of forming an urban assemblage where a monument and casually placed outdoor chairs held similar significance, thoughts are generated which might lead to further thoughts. Through observing and drawing the not-necessarily-grand, somewhat chaotic, mundane parts of actual life in its immanent form, without a superimposed order, one might recognize when we encounter something that carries the potential to disturb us, force us to think, and which might somehow return to us in countless other forms: as a lineage, an urban experiment, a thought, a drawing, but in all cases returning with some “difference.”

Published 10th November, 2025.

Notes

[01] Terunobu Fujimori, “Under the Banner of Street Observation,” trans. Thomas Daniell with Yuki Solomon, Forty-Five: A Journal of Outside Research, 2nd June 2016, http://forty-five.com/papers/154.

[02] In using the term urban assemblage, I refer to Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari's assemblage as a provisional system of heterogeneous human and non-human elements (bodies, buildings, landscapes, furniture, discourses, infrastructures, power relations etc.) each with relative autonomy yet capable of acquiring new capacities through their relationships. From this perspective, urban space becomes a multiplicity that changes across all scales simultaneously. For assemblage, see Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987).

[03] Izumi Kuroishi, introduction to “Selected Writings on Design and Modernology, 1924–47,” by Wajirō Kon, trans. Izumi Kuroishi, West 86th: A Journal of Decorative Arts, Design History, and Material Culture 22, no. 2 (Fall–Winter 2015): 191–202.

[04] Terunobu Fujimori, “The Origins of Atelier Bow-Wow’s Gaze,” trans. Nathan Elchert, in The Architectures of Atelier Bow-Wow: Behaviorology, ed. Yoshiharu Tsukamoto and Momoyo Kaijima (New York: Rizzoli, 2010), 122–29, 123–24.

[05] “Barrack” is the established English translation of the Japanese loanword barakku (バラック), which refers to a makeshift shack or hut built for immediate shelter. Although “barrack” in English often suggests military quarters, the Japanese term carries no military connotation.

[06] Wajiro Kon, “An Examination of Decorative Art (February 1924),” trans. Izumi Kuroishi, in ‘Selected Writings on Design and Modernology, 1924–47,’ West 86th: A Journal of Decorative Arts, Design History, and Material Culture 22, no. 2 (Fall–Winter 2015): 203–5.

[07] Kon, “An Examination of Decorative Art,” 203.

[08] Izumi Kuroishi, "Urban Survey and Planning in Twentieth-Century Japan: Wajiro Kon’s “Modernology” and Its Descendants," Journal of Urban History 42, no. 3 (May 2016): 557–81, https://doi.org/10.1177/0096144216635151; Casey Mack, Digesting Metabolism: Artificial Land in Japan 1954–2202 (Berlin: Hatje Cantz, 2022), 48.

[09] Fujimori, "The Origins of Atelier Bow-Wow’s Gaze," 125.

[10] Kon actually coined the Esperanto term modernologio. Most English‐language scholarship, however, renders it as “modernology”, and I follow that convention here.

[11] Wajiro Kon, "What Is Modernology (1927)," trans. Ignacio Adriasola, Review of Japanese Culture and Society 28 (2016): 62–73.

[12] Kon, "What is Modernology (1927)," 69.

[13] Tom Gill, "Kon Wajiro, Modernologist," Japan Quarterly 43, no. 2 (1996): 198–207.

[14] Kuroishi, "Urban Survey and Planning in Twentieth-Century Japan," 562–68.

[15] Thomas Daniell, "Just Looking: The Origins of the Street Observation Society," AA Files, no. 64 (2012): 59–68.

[16] Thomas Daniell, An Anatomy of Influence (London: AA Publications, 2018), 178.

[17] Genpei Akasegawa, Hyperart: Thomasson, trans. Matt Fargo (New York: Kaya Press, 2009), 16–19; originally published as Chōgeijutsu Tomason (Tokyo: Chikuma Shobō, 1987).

[18] Daniell, An Anatomy of Influence, 179.

[19] Jordan Sand, Tokyo Vernacular: Common Spaces, Local Histories, Found Objects (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013), 89.

[20] Genpei Akasegawa, Terunobu Fujimori, and Shinbō Minami, eds., Rojō Kansatsugaku Nyūmon [Street Observation Studies Primer] (Tokyo: Chikuma Shobō, 1986), 195–96.

[21] Daniell, "Just Looking," 66–67.

[22] During the Edo period (1603-1868), Tokyo (then called Edo) was a city of rivers and canals. These waterways were later filled in to accommodate the roads and railways of modern Tokyo.

[23] Fujimori, “Under the Banner of Street Observation,” n.p.

[24] Tarō Igarashi, "From Ripples to Waves," in How to Make a Japanese House, ed. Cathelijne Nuijsink (Rotterdam: NAi010 Publishers, 2012), 140–42.

[25] Laurent Stalder et al., eds., Atelier Bow-Wow: A Primer (Köln: Walther König, 2013), 14–15; Yoshiharu Tsukamoto, “What Is Made in Tokyo?,” in Urban Flashes Asia: New Architecture and Urbanism in Asia (Architectural Design 73, no. 5), ed. Nicholas Boyarsky and Peter Lang (Chichester, UK: Academy Press, 2003), 38–47.

[26] Momoyo Kaijima, Junzo Kuroda, and Yoshiharu Tsukamoto, Made in Tokyo (Tokyo: Kajima Institute Publishing Co., 2001), 9.

[27] Kaijima, Kuroda, and Tsukamoto, Made in Tokyo, 54.

[28] Yoshiharu Tsukamoto, "Pet Architecture and How to Use It," in Sarai Reader 03: Shaping Technologies (New Delhi: Sarai Media Lab, 2003), 249–54, https://sarai.net/sarai-reader-03-shaping-technologies/; Yoshikazu Nango, "Atelier Bow-Wow’s Approach to Urban and Architectural Research," trans. Nathan Elchert, in The Architectures of Atelier Bow-Wow: Behaviorology, ed. Yoshiharu Tsukamoto and Momoyo Kaijima (New York: Rizzoli, 2010), 321–40.

[29] Atelier Bow-Wow, Pet Architecture Guide Book (Tokyo: World Photo Press, 2002).

[30] Fujimori, "The Origins of Atelier Bow-Wow’s Gaze," 127.

[31] The concepts discussed in this essay are mainly drawn from Gilles Deleuze’s Difference and Repetition (1968) and A Thousand Plateaus (1987, co-authored with Félix Guattari). In addition to these two fundamental works, Deleuze’s extensive body of work also inevitably influences the discussion beyond explicit citations. Deleuze writes in a poetic and layered way, with interlocking terms. I have avoided his specialized vocabulary wherever possible, with the exception of certain terms such as “difference,” “immanence,” and the “capacity to affect and be affected” in basic forms. This section is an intentionally accessible and highly simplified discussion rather than a comprehensive look at Deleuzian thought, as the main aim is to provide context to interpret the lineage of Japanese practitioners discussed in relation to the acts of discovery and creativity embedded in urban survey.

[32] Joe Hughes, Deleuze’s ‘Difference and Repetition’: A Reader’s Guide (London ; New York: Continuum, 2009), 133–35.

[33] Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, eds. Robert B. Pippin and Adrian Del Caro, trans. Adrian Del Caro (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 17.

[34] Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, 17.

[35] Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, 256.

[36] Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, 256–58.

[37] Gilles Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, trans. Paul Patton (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994), 139.Emphasis in original.

Figures

Banner.

View north along Grey Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, c. 1946; Grey’s Monument stands headless after the 1941 lightning strike as an early form of Geordie Thomasson. © Newcastle City Library, Newcastle; reproduced with permission.

01.

Cracks in Bowls at an Eating House, Wajirō Kon and Shōzō Ozawa, 1927. Courtesy of Kon Wajiro Collection, Kogakuin University Library; reproduced with permission.

02.

Map of Restaurants and Drinking Establishments, Ginza,Wajirō Kon and Kenkichi Yoshida, 1927. Courtesy of the Kon Wajiro Collection, Kogakuin University Library; reproduced with permission.

03.

Ginza Fashion Survey Index, Wajirō Kon, 1925. Courtesy of the Kon Wajiro Collection, Kogakuin University Library; reproduced with permission.

04.

Pure Stair case studies from a spread in Rojō Kansatsugaku Nyūmon (Street Observation Studies Primer), Chikuma Shobō, 1986. © Takeshi Suzuki; reproduced with permission.

05.

Tools for Street-Walking, Jōji Hayashi in Rojō Kansatsugaku Nyūmon (Street Observation Studies Primer), Chikuma Shobō, 1986. © Jōji Hayashi; reproduced with permission.