Finding Byaduk: Field Notes

Chuan Khoo

I first encountered Byaduk by suggestion, as a place for a short weekend ‘escape’ from the city, the kind of ‘escape’ that involves spending a few days in the relative quiet of the country. This suggestion prompted an initial visit, which grew into a creative residency that took place between 2017-2018, in which I made—and now, subsequently, continue to make—multiple separate short trips to the small township, an hour’s drive south of Hamilton.[01] As with most towns in the Western District of Victoria, Australia—just as, perhaps, relatively-remote towns around the world—the main street, the Hamilton-Port Fairy Road, is frequently heavy with passing vehicular traffic. A regional public bus stop fronts the local general store. In a rather clever attempt at self-deprecating humour, the store sells wooden carvings of ducks. Byaduk, however, is not the historic preserve of poulterers. The name is an indigenous Australian word, with different translations depending on whom one asks. Officially, the Glenelg & Wannon Settlers & Settlement website suggests Byaduk translates as ‘stone tomahawk’, while the Southern Grampians Shire town information brochure on Byaduk suggests another meaning: ‘running water’.[02] I was later told by the proprietor of the old Byaduk Church that it might have been an old Scottish word, but all I could surmise at this point was that this uncertain etymology was the result of the meandering erosion of terms over multiple generations. Finding Byaduk is a finding of terms, not historical terms but a ‘coming to terms’, a negotiation through encounters with a place.

01. The site of the residency: the old Byaduk church, formerly the Byaduk Uniting Church, built 1864. The Sunday school hall, left, was built in 1899.

Field Notes: Of places to which we might not otherwise venture

It took a decent four-hour drive to get here from Melbourne. My place—a rented house which became my temporary home for the weekend—provided respite from the unfamiliar surroundings. Byaduk is a small town; one could walk through it in under fifteen minutes at a brisk pace. The house is nestled on a side street at the north end of town, where a few other occupants reside. The Byaduk Uniting Church, now simply called the old Byaduk church, sits in the heart of the town, a ten-minute walk from the house, next to the Byaduk Mechanic’s Institute and the statue of Simon Fraser, Byaduk local and a noted hero of the Great War. Its foundation stone was laid in 1864, with the adjoining Sunday school hall built in 1899.Across the main street, the open space in front of a resident’s home displays an interesting arrangement of farming equipment and curios for sale. ‘Peaceful’ is an apt descriptor for such scenes, at least upon first impression. As with any small town, human presences emerge, distant figures milling about their properties. The sun has to catch these distant figures at the right angle to announce what they are doing at any time: walking across the field, idling in a tractor, or moving equipment around their backyards. Sometimes a friendly wave from afar helps to break the monotony. Beyond these intermittent interactions, the Hamilton-Port Fairy Road is busy and heavily used by travellers moving between Hamilton, Port Fairy and Warrnambool. Some of them stop at the cricket oval and rest area. During one of my stays, a family caravan camped at the rest area for an evening or two. As casually explained by the proprietor, peculiar lone cars and their drivers sometimes seek a night’s refuge or two in this quiet town, seldom leaving their vehicles.

02. Nightfall in Byaduk is illuminated predominantly by bright street lamps. Away from the main street, however, it was the glow of lit windows that leak out into the darkness.

Magpies, crows and cockatoos dominate the morning birdsong. The township’s cricket oval—the J. A. Christie Oval—features an immaculately-maintained white picket fence and equally pristine, green lawn. Care is obviously taken to maintain the oval. The ever-present wind can be heard through the rustling of gum trees, the rattling of tin roofing, and the shiver of two giant palms planted on the old church grounds. These palm trees are apparently part of the town’s heritage and cannot be cut down, a covenant of sorts between residents and the trees, the oldest remnant bushland in Byaduk. The biting cold of the morning is particularly felt as air pushes through the passageway flanked by the external walls of the church and the Sunday school hall. In this passageway there are tell-tale signs of nocturnal wildlife: the sounds of scampering possums on the roof at night, small marsupial droppings and some evidence of attempts at scavenging.

A residency for ‘listening’

I returned to Byaduk for a few subsequent, separate stays, acting as a fly on the wall, blending into the landscape. Throughout these different trips, I made it a point to seek out solitude, which was not a difficult thing to do there. It became a means to listen to Byaduk. By listening, I mean not only an auditory process, but a phenomenological involvement of experiencing the place in all of the senses of which I was capable. I use ‘listening’ over ‘experiencing’ in my attempt to foreground what I see as an intimate conversation with the land, as opposed to the grand gesture that an experiential encounter might seem to suggest or describe.

03. The Hamilton-Port Fairy Road by night, when active vehicular traffic is commonplace. A sliver of the Milky Way is captured.

This act of solitary listening was my initial way of ‘finding’ Byaduk, an “antenarrative” that foregrounds the significance of forming nonlinear, incoherent speculations.[03] Standing, sitting amongst the soundscape of insects, birds, traffic, cattle, sheep, machinery, and the rustling of trees swaying in the wind, I noted the soundscape as analogous to those daily urban noises present in a city: new and jangly, yet largely easy to filter out after a while. It would have been odd to hear nothing in the country. Something is always afoot. As things are more spread out, there seems to be more opportunities for sounds to travel. Those sounds that come back off the walls of the old church, the adjoining Sunday school hall and the neighbouring Mechanics Institute are particularly pronounced.

Traffic was one of the more significant contributions to the soundtrack of Byaduk. The north end of Byaduk had a slightly higher elevation, a gentle, almost double crest when viewed directly from the south. The doppler effect of approaching vehicles would telegraph their presence from hundreds of metres away, long before they made their presence known visually, tearing down the main road at (and sometimes over) the 80 kilometre-per-hour speed limit. I was not sure whether the wildlife quietened when this happens, in response to vehicular presence, or if wildlife sounds were simply drowned out by the roar of the traffic. What I do recall was being held hostage by each passing vehicle’s presence, paralysed in both thought and activity in my listening.

Beyond the acoustics of the landscape, which permeated every aspect of being in Byaduk, the wind was another omnipotent presence. It seldom produced the characteristic loud howls we tend to associate with wind. Rather, it simply existed as a force that fluttered past our ears, buffeting and shaking things: sideboards, fences, trees, grass, open doorways, and most certainly, my own body. Casually, I realised that it is often through objects that wind presents itself. In the colder months in Byaduk, I noted the sharp bite that came along with the wind, accentuating the indoor odours of old timber and carpet; the winds of spring and summer brought with them an invigorating swirl of earthly, scorched odours picked up from the ground, the stone walls, and across the fields and paddocks.

Pink skies greeted me on foggy mornings, quickly giving in to the bright blue of day as the rising sun heated Byaduk up at a brisk pace. On clear days the raw, harsh beauty of Byaduk is apparent. Nature reclaims everything eventually. Drainage pipes sustain patches of green and yellow daisies on the otherwise parched grass at the end of the hot summer months. The dark, bluestone walls of the church and faded baby-blue sideboards of the hall contrasted against the deep blue sky like a harmonious triplet of swatches on a colour wheel, juxtaposed over the tanned and dying fibres of grass on the dry ground. Overcast days painted a mellow picture of Byaduk, shrouding my view in soft hues, amplifying the isolation that the landscape brings. Visually, nothing changes much, except tiny movements from flitting insects and grass, or whatever flora the wind could influence and sway. Flocks of sheep would graze as a nebulous collective, quietly chewing their way through the adjacent paddocks, their grey, weathered wool coats bobbing slowly past. Sunsets can be spectacular, as one would expect, golden blue and uninterrupted by the geometry of urban skylines. On a cloudless night, the Milky Way can be observed, even before civil twilight. One can easily imagine hours spent in the evening, looking up at the stars without feeling that time could be better spent elsewhere.

04. The now-defunct and empty Byaduk pool, overlooking the cricket oval. The deep end was estimated to be around 2 metres deep.

05. An old sign on a corrugated tin shed next to Byaduk pool, a likely list of entry fees for the public, and other associated costs of using the pool.

The signs

Peppered around the rural landscape of the township are heritage signs offering short, curious stories of Byaduk’s history. These stories were contributed by residents who grew up in the township. Each sign has a little serial number on the top left corner. There is a sign next to a stone bridge, the same bridge that was chosen to represent Byaduk’s identity in a logo created for the township that adorns these signs. This particular sign described the builder who lived in Byaduk throughout the construction of said bridge, before heading home with all of his tools in a wheelbarrow. Another sign at the now-defunct swimming pool identified the builders and described how families from neighbouring townships congregated there on weekends. There is one that speaks of a flour mill that once stood nearby, now marked only by the presence of the sign, and another describing how the Mechanics Institute continues to host the annual Spring Flower Festival.

06. Heritage signages of Byaduk’s history.

The stories on the signs were what spoke to me most distinctly in Byaduk. These signs are a very literal record of Byaduk’s recent history, and the cracks that have begun to appear on some of the prints reminded me that even such attempts to extend the memory of a place have a finite lifespan. There is a sense of intrigue in these distant accounts, short stories that I suspect carry far more personal connections than can be conveyed or appreciated in their reduced role as inducements to heritage tourism. If written artefacts offer rewards for patient and intrepid wanderers to discover, is there a sense of anticipation, then gratification, experienced by the ones who wrote these stories through this passive interaction? Regardless, careful effort was made to accompany these stories with old photographs to remind the reader of the town’s recent past. It seemed to suggest a subtext, that of a collective memory of Byaduk’s locals, an almost silent wish for their mundane stories to last just that little bit longer, beyond the lifetime of a single person.

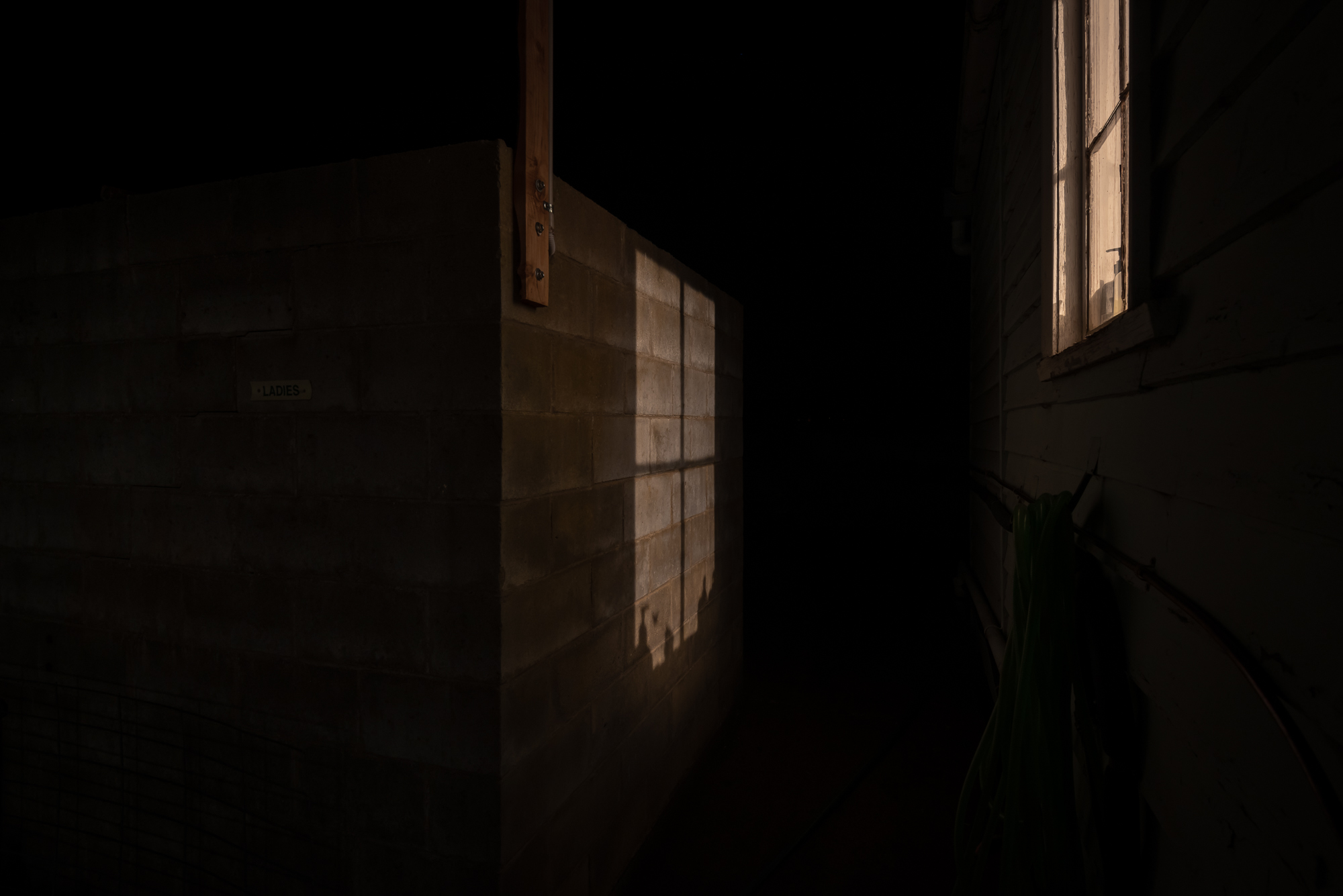

07. Inside the front room of the old church, believed to be used as a coat room.

Indoors, in the hall building, the dusty atmosphere and stillness of the interior hold further moments captured in time. Enlarged prints of old photographs adorn the dark, wooden walls of the hall, documenting activities as far back as the early 1900s. A cradle roll hangs on a wall, carefully protected within a plastic sheet. With each visit, upgrades and slight changes are discernible, the hard work of the proprietor constantly seeking ingenious ways to improve what comfort a 120-year old building can offer. Inside the small church, stained glass windows spill coloured light onto the mostly empty space, the pews having been long removed. In their place, a thin red carpet engulfs one’s view, captured as it is simultaneously in old monochrome photographs, almost as if to prove that the carpet we are seeing in front of us has been untouched over the years. The space now exudes a cosy ambience for work and living. Despite these transformations, the material culture latent in these artefacts seems amplified by the atmosphere of the hall. This was particularly so in a place like Byaduk, the quintessential quiet township that comes alive through the richness of the narratives embodied in the mundane artefacts scattered around, at times randomly, and at others most distinctly intentionally, just like the carefully curated and written signage scattered around town. I interpreted the interior decor as a desire to nurture the somewhat precipitous future of a small, ageing town, to afford past and current residents a memory, a sense of presence in the world, and an identity.

“That’s where I pick my watercress”

My time in Byaduk involved a series of walks, and a series of collections. These walks emerged from a simple curiosity driven by an unfamiliar place. I felt the proverbial call of the land; the stillness of the ground only interrupted by the sounds and feel of my footsteps on the dry grass.Walking past the cricket oval on a side road headed to Penshurst, another town 38 kilometres east of Byaduk, I hear the soothing sound of a small stream—Scott Creek—with a tiny drop and bend, hidden next to the road and right next to a speed limit sign that reads 80 (the speed limit for the outskirts of most country towns in the Western District of Victoria, Australia). It was the church proprietor who first described this spot to me as a place in which to wander. Wild watercress grows where the creek flows, under a willow tree. “That’s where I pick my watercress,” she said, almost absentmindedly, before commenting on the sounds the creek makes. In retrospect, I realised that if Byaduk is indeed the indigenous Australian word for ‘running water’, Scott Creek might be Byaduk. To my own detriment (albeit ultimately humorously so), this creek is wider and deeper than it seems, concealed in part by the thick tangle of watercress. My clumsy attempts to leap over it while carrying my recording equipment resulted in both my feet sinking into the silty banks.

08. An enlarged photographic reprint of the old Byaduk church in its heyday, as the Byaduk Methodist Church, which would later become the Byaduk Uniting Church.

Noticing my interest in seeking out the mundane, and in the heritage signage, in one of my earlier visits I was led on a quick tour by the proprietor and curator of the old church. We walked around neighbouring fields, ducking huge, prickly hawthorn bushes that sprung up around places where skips once stood. We came across the footprint of a house that burnt down in an accidental fire. Further on, I was pointed to traces of circular stone formations in the ground, which hinted at the possibility (possibly remote) that these remnants might be related to the engineering efforts of indigenous Australian peoples, potentially of the Gunditjmara people.[04] It was impossible to verify these speculations without expert knowledge. Subsequent research revealed the proximity of Byaduk to the surrounding Mt. Eccles lava flow, or Budj Bim, as it is known to the Gunditjmara people,[05] which suggests that my the speculation of the presence of indigenous peoples in Byaduk might not be too far-fetched. The walk ended with a collection of more found objects—three glass bottles, a piece of burnt bark, part of a sheep’s jawbone, a lava rock and a decorative cast iron grille from the exterior of the hall—all of which seemed to reflect a part of the Byaduk I experienced.

09. The Byaduk Methodist Kindergarten Cradle Roll. The names on the right column appear to be traced over an older, faded version.

10. Inside the Sunday school hall.

The found objects had stories to tell. As they sat in my studio, looked at, manipulated and talked about, their material culture revealed themselves over time. For example, the phrase “HALF PINT, NO DEPOSIT NO RETURN” embossed on two of the glass bottles was recognisable to those who saw it because it was synonymous with childhood memories of bottled milk, and of the activities that unfolded around the use and re-purposing of those bottles. Casually discussing the etymology of the embossed phrase brought up personal stories, or invited further speculation based on encounters with similar objects. Thus, the richness that each mundane Byaduk object possessed shifted the project towards exploring their semiotics and material culture: these found objects became conversation pieces. Sometimes they would speak to Byaduk: where they were found, why they were there. Other times, they simply pointed to the personal memories and relationships we associate with the type of object. A new question emerged: could such conversation pieces also become conduits for ephemeral digital data? Could they couple stories of the now—the environmental effects of Byaduk—with their semiotic richness and cultural, historical connection with Byaduk? Could using found objects identify a means of working with poetic, digitally connected things?

11. Two of the bottles found; a small lava rock the size of a clenched fist; decorative cast iron grille from the exterior of the Sunday school hall; part of a sheep’s jawbone.

To test these thoughts, two activities unfolded after the walks and object collection activities. The first was to construct an environmental sensing apparatus, to record Byaduk. The second was to develop a process by which the found objects become coupled with the sensor readings generated.[06] In this process, I noted the specific moment in which a use for the milk bottles was found:

“It was a serendipitous discovery that led to the first result of this project. During the second stay of the residency, as I completed the installation work on the sensing units and solar panels, I have placed the bottles outside on a table. The glass bottles, in their upright position, became wind instruments as a gust arrived, resonating with soft howls just as one might hear by blowing across the top of a bottle neck. It seemed natural that wind emerged as the environmental quality to respond to these bottles, partly due to its omnipresence in the township. The poetry of the relationship between wind and glass bottle also played an important part in selecting this coupling: the futility of storing or catching wind in any vessel, against the affective experience of listening to a singing glass bottle in the wind.”

12. The grassy and rocky site where the first of the abandoned milk bottles was found.

The first objects used, the milk bottles, were repurposed into Wind objects, and relied on custom electronics and programming that in turn re-appropriated the technologies related to the Internet of Things (IoT) to convey near real-time snapshots of wind conditions in Byaduk. They are electronic appliances of an evocative, poetic disposition, that sought to share a quality of a distant place. Having both the technology of digital connectivity and the physical medium itself—glass bottles, re-appropriated from their originally intended use and context—was critical in examining my own role as a technologically-driven creative practitioner spending time in Byaduk. By bringing out the evocative potential of both tangible and intangible interactions—the glass bottle and the IoT—I was able to ponder the possibility of using functional IoT systems as aesthetic interventions for phenomenological telepresence: under the hood, these objects could be technologically complex, yet by virtue of their tangible presentation and ‘real-world’ aesthetics they tell us about the conditions of a remote place through an interface with which we can relate. They afford us opportunities to interpret them at a semiotic, reflective level.

13. I placed bottles placed outdoors on the table to test the sound of the actual wind in Byaduk, in contrast to the artificially-generated ones that the bottles will be exposed to. Mounted on the exterior wall is the sensing apparatus.

14. The Wind objects.

Field Notes as inspiration

It would not have been possible to discover the affective qualities of Byaduk without the prior ethnographic work, and more can be revealed still. The process of translating and attempting to condense these ethnographic observations into the various sensory affordances that each found object could represent or emit emerged as a key theme of the project. The process was built upon the narratives embedded in each observation, each possibility drawn out from observations. The ‘field notes’ here therefore accompany the project as its foundational material; they are not intended or interpreted as factual observations, but tend towards immersing oneself back in the phenomenological qualities of the site.The walks, and the experience of encountering the objects in situ, presented an ideal opportunity to conduct visual and reflexive ethnography through photography.[07] In later visits this was complemented by audio-video recordings, with the intention to produce a sonic ethnography in which video footage supported a visual memory of the relatively unchanging, mundane soundscape.[08] While not initially considered central to this experimental project, it is important to note the contribution these recordings made in capturing the “empathetic engagements” of the found objects.[09] Similarly, in field recording, an “attention to dramaturgy” compels the listener to recall minute moments captured in the recordings.[10] The unending roar of road traffic, birdsong, the clicking of grasshoppers, rustling of the palm trees and incidental slaps of the fly screen curtain hitting on the doorframe of the hall formed a distinct imprint of Byaduk—a “soundmark” as a reflective tool.[11]

This in turn afforded phenomenological re-visitations of the place whilst working in the studio, playing back the videos on loop while ideating, again allowing nonlinear “antenarratives” to further inspire responses.[12] Along with the notes, this collated material provided a sufficiently vivid means to recall the environmental conditions of Byaduk.

Coda: Questions at the lost and found

It is important to recognise and discuss the nature of what constitutes an ‘abandoned’ object. With the exception of the iron grille—which was kindly donated by the proprietor for the project—the remaining objects are articles that appear to have been discarded or deserted for an extended period of time. In the case of the milk bottles, the act of taking them is a necessity in allowing such works to exist, but it was also made with a consideration of whether the removal of such an object would cause a disruption to the order and condition of Byaduk. I saw ‘taking’ these objects not as an act of removal, but as mutually communicative and reciprocal. The objects are representations of a place, much like museum artefacts. However, these objects remain connected to Byaduk on two levels. As with museum artefacts, the first connection is related to the material culture of the object, its prior existence and use in Byaduk, and the narratives evoked from understanding how it, and many others like it, existed there. The second, and perhaps the key connection here, is the nature in which the environmental readings in Byaduk get streamed, processed and translated into dynamic manipulations of the objects. In the case of the Wind objects, the sound of air moving around the neck of the milk bottles is produced by tracking the wind intensity as detected at the old Byaduk church. The objects are not severed vestiges simply removed from their original ‘found’ locations but are what I consider to be affective telepresence devices used to express an ephemeral condition, and, hopefully, allow us to forge a resilient, emotive connection between object and place.As a practitioner, I am also conscious of my relationship with the town of Byaduk, and the implications of the relationship on this research. Like the almost-mythical Johnnie Daspar, the bridge builder who hauled his wheelbarrow of tools to and from Byaduk, I made the drive out to Byaduk, installed and tested the Internet-connected sensors, and recorded observations, before returning to Melbourne to finish the artefacts. This voyage and return felt almost as precious as those stories recorded on the heritage signages.

Perhaps this could signal a concluding phase of the project, when the ‘found’ objects get returned to their original locations in Byaduk, once the devices have finished serving their purpose. When that moment might be I do not know. If they never return to Byaduk, perhaps they will simply become a remote incarnation of the signposts, representing a desire to extend the township’s existence beyond its geographical location, and passing to more people who might chance upon the ‘finding’ of Byaduk.

Notes

[01] The Australian Bureau of Statistics 2016 Census records a population of 123 (accessed 19th September, 2019).

[02] Povey, D. 2019. “Byaduk Pioneers & History.” Glenelg & Wannon Settlers & Settlement [online], (accessed 19th September, 2019); South Grampians Shire Council. n.d. Byaduk (accessed 19th September, 2019).

[03] Developing the term “Antenarrative” from Vincent Meelberg. See: Meelberg, V. 2019. “Noise Is What You Make It. Interpreting Auditory Environments As Sonic Ambient Narratives.” Proceedings of Inter.Noise 2019, Madrid, 16th-19th June, (accessed 19th September, 2019).

[04] Coutts, P. J. F., Frank, R. K., Hughes, P., and Vanderwal, R. L. 1978. Aboriginal Engineers of the Western District, Victoria. Melbourne: Ministry for Conversation, p.1.

[05] Builth, H. 2010. “The Cultural and Environmental Landscape of the Mount Eccles Lava Flow.” In L. Byrne, H. Edquist, & L. Vaughan (eds.), Designing place: an archaeology of the Western District. Melbourne: Melbourne Books, p. 80.

[06] Details of this sensing apparatus and technology can be found in a paper detailing the Finding Byadukproject presented at the Annual Design Research Conference 2018. See: Khoo, Chuan. 2018. “Finding Byaduk: thinking objects as prototypes of affective telepresence with digital data.” Proceedings from Annual Design Research Conference (ADR18), Sydney, Australia 27th-28th September (accessed 19th September, 2019).

[07] For the use of photography in ethnographic research see: Pink, Sarah. 2006. Doing Visual Ethnography: Images, Media and Representation in Research, 2nd Edition. London; Thousand Oaks; New Delhi: SAGE Publications, pp.67, 75.

[08] For the use of sound in ethnographic research, see: Gherson, W. S. 2012. “Sonic ethnography in practice: students, sounds, and making sense of science.” Anthropology News, Vol. 53 No.5, pp.5-12.

[09] Pink, Sarah. 2009. Doing Sensory Ethnography. Los Angeles; London; New Delhi: SAGE, p.156.

[10] English, L. 2014. “A Beginners Guide to… Field Recording,” FACT Magazine, 18th November (accessed 19th September, 2019).

[11] Schafer, R. M. 1993. The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World. Rochester, VT: Destiny Books, p.10

[12] Meelberg, V. 2019. “Noise Is What You Make It,” passim.

Figures

Banner.

The Wind objects.

01.

The site of the residency: the old Byaduk church, formerly the Byaduk Uniting Church, built 1864. The Sunday school hall, left, was built in 1899.

02.

Nightfall in Byaduk is illuminated predominantly by bright street lamps. Away from the main street, however, it was the glow of lit windows that leak out into the darkness.

03.

The Hamilton-Port Fairy Road by night, when active vehicular traffic is commonplace. A sliver of the Milky Way is captured.

04.

The now-defunct and empty Byaduk pool, overlooking the cricket oval. The deep end was estimated to be around 2 metres deep.

05.

An old sign on a corrugated tin shed next to Byaduk pool, a likely list of entry fees for the public, and other associated costs of using the pool.

06.

Heritage signages of Byaduk’s history.

07.

Inside the front room of the old church, believed to be used as a coat room.

08.

An enlarged photographic reprint of the old Byaduk church in its heyday, as the Byaduk Methodist Church, which would later become the Byaduk Uniting Church.

09.

The Byaduk Methodist Kindergarten Cradle Roll. The names on the right column appear to be traced over an older, faded version.

10.

Inside the Sunday school hall.

11.

Two of the bottles found; a small lava rock the size of a clenched fist; decorative cast iron grille from the exterior of the Sunday school hall; part of a sheep’s jawbone.

12.

The grassy and rocky site where the first of the abandoned milk bottles was found.

13.

I placed bottles placed outdoors on the table to test the sound of the actual wind in Byaduk, in contrast to the artificially-generated ones that the bottles will be exposed to. Mounted on the exterior wall is the sensing apparatus.

14.

The Wind objects.

https://doi.org/10.2218/9gs9kg18