Introduction: On Drawing On

Chris FrenchOn behalf of the Drawing On: Presents editorial team: Konstantinos Avramidis, Chris French, Piotr Lesniak, Maria Mitsoula and Dorian Wiszniewski.

Drawing On was originally conceived as a record of a symposium, Plenitude & Emptiness, held in Edinburgh between 4th and 6th of October 2013.[01] This symposium, as Dorian Wiszniewski notes in the prologue to this first issue of Drawing On, took the Glasgow poet Norman MacCaig’s Presents as both the operative principle guiding the structure and organisation of the event and as a guiding call for participants. Extending MacCaig’s gifts of “plenitude” and “emptiness” the symposium offered each presenter a forty-minute slot, either to ‘fill’ with material (a full-length paper, presentation or event) or to ‘leave empty’ (to present a short text, film, animation, or project and luxuriate in a longer period of discussion).[02] In addition, rather than prescribing a tight thematic frame, the call for papers invited participants to “unwrap… carefully” those relations frequently encountered in design-led research – relations between method and content, theory and knowledge, or design and research, for example – using any and all modes necessary to communicate these relations.[03] To our great delight, the speakers took up this call, and presentations ranged from extended oral presentations to interactive collage salons, recordings, performances, architectural models, installations and exhibitions.

01. Preparations for a collage salon. Participatory presentation, Tonia Carless, Plenitude & Emptiness symposium. 6th October, 2013.

Nine of the twelve papers presented at the event are included here – with additional contributions from two of the keynote speakers, Hélène Frichot and Marc Boumeester, and so in some respects the journal remains true to its original intent.[04] However, in the process of collating, reviewing, amending, editing, proofreading and, finally, formatting the various papers from this event the journal has become something very different to the one originally envisaged. What became clear in the re-presentation of these original presentations is that the effective communication of design-research demands a re-thinking of the conventional journal format, not just as a document but as a critical procedure in the on-going production of design-research material. The range of means employed in the various research projects presented at the symposium has thus come to reshape this journal conceptually, formally and methodologically. What will hopefully become apparent through exploring this first issue, Drawing On: Presents, is that the journal has become more than a simple record of events. It represents an attempt on the part of those involved (the authors, editors and reviewers) to bring together questions of presentation, re(-)presentation and research in the form of an evolving publication.

02. Participants in the Plenitude and Emptiness Symposium: Hélène Frichot, Sophia Banou, Marc Boumeester, Ersi Ioannidou, Sepideh Karami, Miguel Paredes Maldonado, Julieanna Preston, Thomas Rivard, Helen Runting & Fredrik Torisson, Randall Teal

Presenting to Oneself and to Others

Perhaps unlike other journals, Drawing On openly sets out to be an active (design) participant in the process of making and presenting research. In presenting material from a wide range of design-research projects (either complete or incomplete) and from scholars and practitioners at different stages of their careers, it seeks to question the means by which such work is presented and read, not only by readers new to the material but also by the authors responsible for that material. As such it attempts to establish a new format for presenting design research.Accepting that design-led research involves – indeed relies upon – multiple modes and means of presentation to allow thinking to develop, Drawing On recognises that projects emerge, as Dorian Wiszniewski notes in the Prologue, through serial presentation to both oneself and to others.[05] Presenting to oneself invites us to consider the reciprocity (if not the direct correlation) between the means employed and the object of our inquiry. One might draw in order to interrogate something (object), in order to present or reveal to oneself findings. In presenting these findings to others one subsequently exposes not only these findings but also the act of drawing (means), the drawer (author or subject) and the drawing itself (a new, secondary object) to the same critical scrutiny as that initial ‘something’ that formed the object of the drawing. In short, all our methods are open to question; in any design research enquiry there are recurrent slips between subject, object, and means. Consequently, as design-researchers we must become accustomed to following, what Peter Cook describes in his introduction to Nat Chard and Perry Kulper’s recent contribution to the Pamphlet Architecture series, “a zigzag path toward the unknown,” a trajectory that leads away from the security of neutrality and appeals to impartiality, and instead leads towards the unforeseen and unforeseeable.[06]

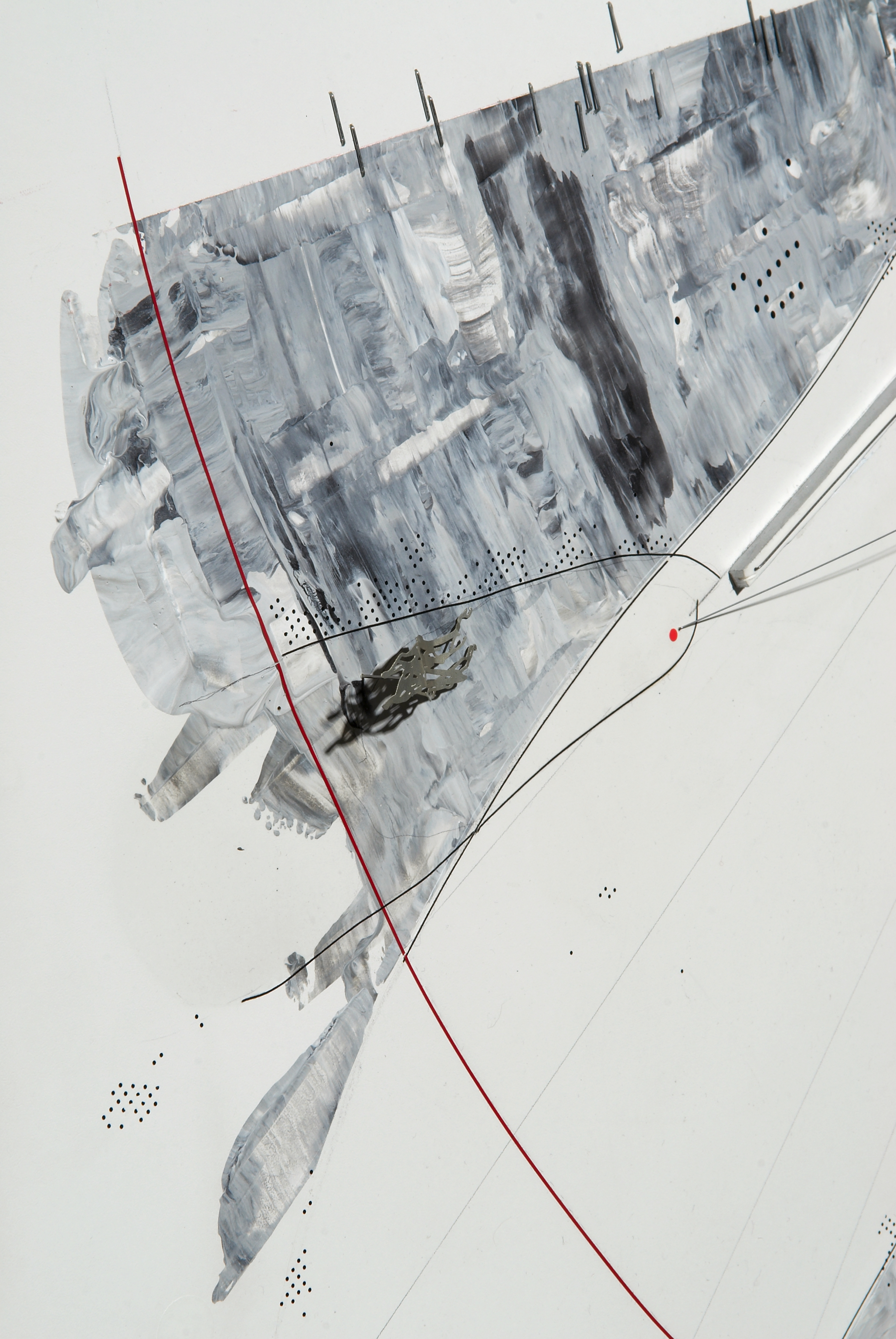

03. Instrument 7. High-speed flash photograph of paint flying through the drawing pieces. Nat Chard.

Nat Chard’s work exemplifies such a path.[07] In a series of evolving studies Chard constructs catapults to throw paint at manipulated picture planes. In these studies the flight of the paint is frozen in the flash of a camera and charted, the interaction between the paint and a ‘drawing piece’ – an elaborate ‘figure’ suspended in front of the picture plane – is observed, the splatter of the paint is recorded, and the effects of the paint on the drawing (the creation of a new drawing) are documented. It might be possible, as Chard notes, to approach each of these scenes scientifically, as forensic sites, but this is not the intention behind these devices.[08] While the catapults might appear to be means of finding answers, these ‘instruments’ precede and deny scientific application.[09] Instead, as Chard notes, “working with the instruments… nurture[s] the very conditions that are discussed by the drawings,” namely uncertainty, doubt and curiosity.[10] As such these instruments facilitate the discovery of something that cannot be pre-figured;[11] they discover and present questions rather than answers. Chard notes:

There’s a thing I want to happen and there’s this other thing that I desire more… which is beyond what I want to happen.[12]

Between the moment that the trigger of the catapult is released and the firing of the camera shutter to produce the image there exists a gap, a space of enticing possibility where this ‘other thing’ might occur.[13]

It is here that Chard encounters a ‘paradoxical shadow’ floating in space, hovering between drawing piece and picture plane; a shadow in the literal sense but also a metaphorical shadow untethered from its material twin, a shadow that registers the presence of something unseen or unknown, a haunting shadow that invites us to speculate as to the nature of the object that produces it.

For Chard, the methods employed in the inquiry therefore become simultaneously the object of study and means for informing thinking; they form “a working and research method to try to make the tools through which [to] think.”[14] In this way they become means for momentarily clarifying the ever-shifting ‘object’ of an enquiry.

04. Instrument 5. High-speed flash photograph of paint flying through the drawing pieces. Nat Chard.

Desirous Pursuit: the Not-yet-known and the Un-knowable

It is not by chance that Chard describes the unknowable ‘other thing’, this ever-shifting object, as an object of ‘desire’. Desire, as Penelope Haralambidou recognises, is present in all architectural drawing. It is brought about by the “suspension of pleasure… arising from the serial nature of architectural drawing (from the movements between plan, section, elevation, etc.),” from the promise of the drawing that follows and of the revelation that that drawing might bring.[15] This combination of an inherent seriality of architectural production and desire is a key component of design-research. As Haralambidou notes:The pleasure [embodied by architectural drawing] derives from a combination of information… leading to a slow blossoming of the designed structure in the mind.[16]

While here Haralambidou is describing the architectural object, her research makes clear that this ‘blossoming’ extends to thought itself; the combination of architectural drawings to form a ‘designed structure’ is, in her work, comparable to processes by which we come to understand. Through her proposition for The Fall (“a composite building, a house for a female protagonist, comprising the linear architecture of her pedestrian journey, [a] pictorial garden… and the sinuous trajectory of her fall”) for example, we begin to understand Marcel Duchamp’s use of geometry, the relative significance of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa (or Lady on a Balcony) to Duchamp’s perception of vision, and also something of Haralambidou’s methodological processes.[17] Crucially this understanding cannot be directly deployed or ‘used’, rather, it is an understanding that occasions further ‘knowings’ and an understanding of how we might come to know, of how we might inquire. It is an understanding borne of, as Haralambidou notes, the processes by which we examine, assemble, project into, contrive and conceive an object of thought external to those objects that enable thought (in this case the drawings themselves). This is the ‘other thing’ that that we desire; as Chard’s work evidences and Haralambidou’s practices embody, design research expects a knowledge that cannot yet be revealed, it develops a means by which we understand as much as an object that we understand.

05. The Fall, detail of the Waterfall. Penelope Haralambidou.

Therefore, while in conventional architectural practice “drawing,” as Haralambidou rightly notes, “is in advance of the thing it describes,” in design research drawing also comes in advance of understanding; it precedes knowledge and allows for the opening up of further inquiries.[18] This is the second (and perhaps more significant) quality of architectural drawing implied by Haralambidou’s invocation of drawing as desiring practice: no one form of drawing (no one scale or projection, for instance) can contain all information necessary to describe fully the object under investigation. Furthermore, no one drawing can ever completely encapsulate something known. Instead, design research must produce multiple drawings, multiple ‘speakings’ through which we both develop and question our understanding (and through which we, temporarily, satiate our desire to know).[19]

06. Undressing. Mixed media drawing by Penelope Haralambidou, 1997, photograph Andy Keate, 2009. © Penelope Haralambidou. Reproduced by permission of the author.

Pose and Precarious Poise

This is one of the challenges inherent in design research: the presentation of an enquiry that is, by its very nature, multiple. As Chard readily acknowledges of his own work, while his ouput might be clear for him as author it represents something very different to us as readers or viewers.[20] This point of difference is where this journal aims to locate itself – in the gap between author and reader created by the diverse nature of an enquiry. As the slippages evoked above suggest, the relationships between object, subject, means and author are complex but, as both Chard and Haralambidou’s work makes clear, these relationship form a significant part of our thinking processes. Unfortunately these relationships (between image and text for instance) are far more intricate than many conventional outputs are able to accommodate.[21] Consequently, what Drawing On puts forward is a format that encourages, to use Deleuze’s term, a “practical assemblage” of constituent parts as a means by which to derive knowledge.[22] It aims to expose connections and relationships between practices, to become a means by which work that has been produced is presented again – to both the authors themselves and to others – as part of a process of serial re-presentations. The intention here, therefore, is not to reduce the gap between author and reader, but to intensify and dwell in this gap by exposing and exploring the different means employed by individual (or collective) researchers.To do so each submission to Drawing On is multiple; each ‘paper’ includes a formatted text with all the requisite illustrations, notes, references, etc. and in addition a number of further modes, open to the author. Here, the various outputs (modes) become objects again, and by opening up these objects in all their guises (as method, as means, and as output) the journal aims to allow the work presented to be continually re-formed. In this way we hope that the journal will make an active contribution to the various research projects documented within. With this in mind, in compiling the ‘papers’ presented here we, as editors, have endeavoured to retain the “precariousness” of the “poise” demonstrated by the various contributors, while nonetheless representing their offerings as completely as we are able.[23] As a journal documenting both outputs and methodological approaches – approaches that we feel are exemplified but certainly not exclusive to design-based research – we do not make any claims to ‘completeness’ or to conclusions. Rather we aim to set up a reading across the multiple pieces presented here (both those authored outputs that collectively form a ‘paper’, and the collected ‘papers’ that form this issue).

As will become apparent in exploring this issue, in each authored ‘paper’ the nature of the assemblage (and the relationship between the components) is different. Helen Runting and Fredrik Torisson’s musings on BIG’s 8 House in Copenhagen for example derive from a scrutiny of the distributed image of the building via social media. Taking this ‘marketing material’, and the now infamous ‘Yes Boss!’ video, as a starting point, Runting and Torisson examine the formative, re-productive power of those images. Working with and from these images, they develop a nuanced critique not only of the 8 house, but of Bjarke Ingel’s larger project of ‘happiness’.

In contrast spatial artist Julieanna Preston’s pieces prioritise the performance of (the) work. Her contribution here presents two re-framings of a site-specific work performed in the Whau River Estuary, Auckland. The original work, entitled ‘Moving Stuff’, is absent, and what Preston presents here through one video entitled ‘Stratified Matter’ and another chronicling her presentation at the Plenitude & Emptiness symposium are attempts to keep the work ‘moving’ and to communicate appropriately the means and performance of her labour, to use a phrase central to Julieanna’s endeavours.

Ersi Ioannidou’s piece similarly documents the framing and re-framing of a research project. Here Ioannidou elaborates upon an earlier research project and, at the same time, opens up a new inquiry into referencing conventions. Through the re-presentation of nine notebooks Ioannidou develops the basis of a digital ‘machine’ that both documents and encourages association-making, an interactive animation that conveys something of the original project while inviting us, the readers, to create and re-create the project and further projects.

Similarly, Sophia Banou invites us, through both her text, the animation of images and more directly through the two installations documented within, to compose our own image of the city. In so doing Banou asks questions of representation, but also more critically of how we engage with and record space. Through a description of optical devices, and in particular the kaleidoscope, Banou explores how conventional architectural representation privileges the static, thereby potentially overlooking the desirable and delightful aspects of kinetic, fleeting and transitory experiences that make up everyday urban life. For Sepideh Karami it is in these fleeting, shifting moments that we find a radical project of architecture; the stationary Standing-Man of Taksim square becomes a lens through which we understand gaps, pauses, absences as heavily politicised space-making practices. Here, through a series of interjecting voices, Karami describes how by breaking regular patterns we might challenge prevailing systems of governance and open up new types of urban space.

Three papers included in Drawing On: Presents directly explore the connection between pedagogy, theory and practice. Marc Boumeester’s text describes a framework for studio production that explores the role, nature and affective capacity of various media. The accompanying videos, products of an architectural design studio guided by Boumeester’s experiences as a filmmaker, explore this affective capacity directly. Rather than concerning themselves with the design of an object these films focus on political activation and creative intervention; they are programmatically as much as aesthetically driven. In a similar manner, Thomas Rivard’s paper describes the interplay of a personal research project looking at narrative and myth with studio pedagogy. Through a description of a design studio on Cockatoo Island in Sydney Harbour, and a series of drawings emerging from this studio, Rivard explores the space of those ‘imperfect reflections’ arising from any site investigation. He takes these reflections as the basis for an approach to architectural and urban design praxis that encourages individual, subjective responses to the city, and as the basis for propositions that exist in the slippages between place, what we perceive, and what we experience. Randall Teal’s paper includes a reflection on his own workings, in this case a series of paintings developed not for a specific client or exhibition but as a means of revealing or, to use Teal’s words of ‘forgetting’ what was previously considered ‘known’. Between these pieces and a reading of Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Teal describes a rethinking of thinking encouraged in his studio teachings, a rethinking that challenges accepted, instrumental approaches to architectural design.

Picking up on this challenge to instrumentality, Miguel Paredes Maldonado explores questions of utility in architectural practice through a critique of the classical notion of utilitas. Through the writings of Bernard Tschumi, Giorgio Agamben and Georges Bataille, and through challenges to classical utility described as the dysfunctional, the obsolete and the dissipative, Maldonado describes a rethinking of utility (and associated notions of ‘value’) as a spectrum of ‘usefulness’. In a second, parallel voice he describes two projects, MEIAC and Doodle Earth, both of which explore the notions of a spectrum of usefulness directly.

Drawing on: Presents

The collection of papers assembled here in Drawing On: Presents becomes, as we editors hope (and, as is always the case with new endeavours, are at once inclined and almost obligated to hope), far more significant than a simple documentation of presentations. Beyond simply recounting and illustrating the presentations of a group of researchers, scholars and practitioners at a conference, this issue provides an opportunity for those authors to frame and re-frame their own production. Furthermore, it is our intention that the journal itself plays an active part in contributing to the continuing research inquiries of the various contributors. This, as noted above, is a critical component of this journal. At times the assembly of this first issue has quite literally involved ‘drawing on’ (adding to as much as editing out) the work put forward for inclusion. In the development of a suitable methodology we as editors have involved ourselves in the re-framing process (to the chagrin no doubt of many of the authors); we have taken a particular stance on the work and re-positioned the various pieces (both within an individual submission and as a collected assemblage). In this way, we hope not only to present the inquiry effectively to a readership new to that work but also to offer something to the authors of the work, a final ‘present’ arising out of the symposium and a voice in a continuing sequence of dialogues surrounding the work. In reading, exploring and navigating this journal, and in engaging with this work as a ‘productive assemblage’ we hope that you will become as engaged, immersed and eventually, to echo Dorian Wiszniewski’s prologue, “lost” as we have. We hope, however, that this immersion will lead to new means of navigation, new paths, new inquiries and new sets of research questions that may, in turn, be presented as further steps into the (hopefully) ever-widening abyss.Published 24th September, 2015.

Notes

[01] The symposium was organised by Konstantinos Avramidis, Chris French, Piotr Lesniak and Maria Mitsoula, the editors of this first issue of Drawing On and members of the PhD Architecture by Design community at the University of Edinburgh, under the guidance of Dr Dorian Wiszniewski, Programme Director of the PhD Architecture by Design programme. Further details and documentation of the event can be found at http://bydesignsymposium.blogspot.co.uk (accessed 12th July, 2015).

[02] MacCaig, Norman. 1974. ‘Presents’ in MacCaig, Norman. 1993. Collected Poems. London: Chatto & Windus, p.316.

[03] MacCaig, Norman. 1974. ‘Presents’.

[04] Each of these papers (with the exception of Hélène Frichot’s invited contribution) has been through a process of peer-review and subsequent revision, and we are grateful to our panel of reviewers for their input and advice.

[05] Wiszniewski, Dorian. 2015. ‘Drawing on Plenitude & Emptiness’ in Drawing On, Issue 01 (Drawing On: Presents).

[06] Cook, Peter. 2014. ‘Chard and Kulper: Scary Guys’ in Chard, Nat & Kulper, Perry. 2014. Fathoming the unfathomable: archival ghosts + paradoxical shadows. Pamphlet Architecture 34. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, p.4.

[07] In the text that follows I will refer to the work of Nat Chard and Penelope Haralambidou. Both Nat (Drawing Uncertainty, Friday 4th October, 2013) and Penelope (A Gift from Vision to Touch: Marcel Duchamp and the Architecture of Desire, Saturday 5th October 2013) were keynote speakers at the Plenitude & Emptiness symposium; footage of their lectures is included as part of this introduction. Their fellow keynote speakers are represented here through edited papers: Hélène Frichot provides ‘Five lessons in a ficto-critical approach to design research’ as a précis to this issue, while Marc Boumeester’s paper ‘The bodiless shadow: towards a meta-medial framework’ is revised and included here as a peer-reviewed contribution.

[08] “The paint that I am using is latex paint. Latex paint is a non-Newtonian fluid like blood, and there are very sophisticated algorithms for understanding narratives from the splatter of blood… Latex paint operates in the same way, so there is a way of reverse engineering these drawings.” Chard, Nat. 2013. ‘Drawing Uncertainty’. Plenitude and Emptiness: Symposium on Architectural Research by Design. University of Edinburgh, 4th October 2013.

[09] Their only application, to stick with the term in order to refute it, is the determination of yet more, and greater, uncertainty: “While their instrumental appearance might seduce someone to take the drawings they produce seriously, they are also practical devices. Searching for the nature of that practicality has provided a way to work out drawing the uncertain.” Chard, Nat & Kulper, Perry. 2014. Fathoming the unfathomable: archival ghosts + paradoxical shadows. Pamphlet Architecture 34. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, p.46.

[10] Chard, Nat & Kulper, Perry. 2014. Fathoming the unfathomable: archival ghosts + paradoxical shadows, p.56.

[11] As Peter Cook notes: “It is surely the purpose of real research to contrive as well as document. Most so-called architectural researchers have carefully chosen to ignore that…” Cook, Peter. 2014. ‘Chard and Kulper: Scary Guys’ in Chard, Nat & Kulper, Perry. 2014. Fathoming the unfathomable: archival ghosts + paradoxical shadows, p.4.

[12] Chard, Nat. 2013. ‘Drawing Uncertainty’. Plenitude and Emptiness: Symposium on Architectural Research by Design. University of Edinburgh, 4th October 2013.

[13] Chard describes the procedure as follows: “when I am working with these [instruments], when I’m throwing the paint for instance, I have my finger on a trigger… I haven’t got to the stage where I really know when the catapult is going to go off and I’ve aimed the catapult for what I want to happen on the throw of paint but I’m firing the camera, the flash manually because the chance of capturing or not capturing the throw of paint is part of the pleasure of doing this… The paint goes and I, as quickly as possible, fire the camera and then I can go to the camera and see, for instance, a range of things: one, did I capture the paint and, two, is what I captured interesting at all? And then, what did it hit in terms of the drawing instrument and what did it draw as a consequence?” Chard, Nat. 2013. ‘Drawing Uncertainty’. Plenitude and Emptiness: Symposium on Architectural Research by Design. University of Edinburgh, 4th October 2013.

[14] Chard, Nat. 2013. ‘Drawing Uncertainty’. Plenitude and Emptiness: Symposium on Architectural Research by Design. University of Edinburgh, 4th October 2013.

[15] Haralambidou, Penelope. 2013. Marcel Duchamp and the Architecture of Desire: The Blossoming of Perspective. London: Ashgate, p. 12.

[16] Haralambidou, Penelope. 2013. Marcel Duchamp and the Architecture of Desire, p. 12.

[17] Haralambidou, Penelope. 2013. Marcel Duchamp and the Architecture of Desire, p. 36.

[18] Haralambidou, Penelope. 2013. Marcel Duchamp and the Architecture of Desire, p. 12.

[19] Our colleagues Mark Dorrian and Adrian Hawker use the term “heteroglossia’ to describe this production: “Instead of arriving at a statement of fact, we end up with a kind of heteroglossia that circulates around the object. Where research, as normally thought, aims to arrive at a result that is 'beyond' interpretation, the output of design as research is necessarily delivered, in important ways, prior to interpretation.” Dorrian, Mark and Hawker, Adrian. 2003. ‘The tortoise, the scorpion and the horse – partial notes on architectural/research/teaching/practice’ in The Journal of Architecture, Vol.8 No.2, p.187.

[20] Chard (‘Drawing Uncertainty’. Plenitude and Emptiness: Symposium on Architectural Research by Design) invokes Todarov’s reading of Rimbaud: “the sentences that make up the text are comprehensible in themselves, but the object that they evoke is never named, and thus we may hesitate as to its identification… the interpretative process is radically changed when symbolic invocations, however ingenious, find themselves deprived of a pedestal.” Todarov, Tzevtan. 1982 (1978). ‘Indeterminacy of Meaning?’ in Symbolism and Interpretation, trans Catherina Porter. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, pp.84-7.

[21] As W.J.T. Mitchell (through Jefferson Hunter) notes, even existing image-led forms of presentation are limiting. For instance, the photographic essay “involves the straightforward discursive or narrative suturing of the verbal and the visual: texts explain, narrate, describe, label, speak for (or to) the photographs; photographs illustrate, exemplify, clarify, ground, and document the text.” This format is less applicable still to the presentation of design research. Mitchell, W.J.T. 1994. 'Beyond Comparison: Picture, Text, and Method’ in Mitchell, W.J.T. 1994. Picture Theory: Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation.Chicago: University of Chicago Press, p.92.

[22] “Knowledge is a practical assemblage, a ‘mechanism’ of statements and visibilities.” Deleuze, Gilles. 2006 (1986). Foucault, trans. Séan Hand. London: Continuum, p.44.

[23] Wiszniewski, Dorian. 2015. ‘Drawing on Plenitude & Emptiness’ in Drawing On, Issue 01 (Drawing On: Presents).

Figures

Banner.

Preparations for a collage salon. Participatory presentation, Tonia Carless, Plenitude & Emptiness symposium. 6th October, 2013. Photograph: Aikaterini Antonopoulou.

01.

Preparations for a collage salon. Participatory presentation, Tonia Carless, Plenitude & Emptiness symposium. 6th October, 2013. Photograph: Aikaterini Antonopoulou.

02.

Participants in the Plenitude and Emptiness Symposium. Photographs: Aikaterini Antonopoulou.

03.

Instrument 7. High-speed flash photograph of paint flying through the drawing pieces. Photograph: Nat Chard. © Nat Chard. Reproduced by permission of the author.

04.

Instrument 5. High-speed flash photograph of paint flying through the drawing pieces. Photograph: Nat Chard. © Nat Chard. Reproduced by permission of the author.

05.

The Fall, detail of the Waterfall. Drawing by Penelope Haralambidou, 1997. © Penelope Haralambidou. Reproduced by permission of the author.

06.

Undressing, mixed media. Drawing by Penelope Haralambidou, 1997. Photograph: Andy Keate, 2009. © Penelope Haralambidou. Reproduced by permission of the author.

https://doi.org/10.2218/x35m7x78