The Limits of the Useful: Revising the Operational Framework of Usefulness in Architectural Production

Miguel Paredes Maldonado

This paper constitutes an attempt to simultaneously determine the nature of usefulness and challenge utility as a dominant criterion for the evaluation of architectural production. While its approach can initially be considered theoretical – that is, based on the examination of a series of critical positions – the ultimate goal of this piece is to articulate how this conceptual challenge to utility can be mobilized as a methodological approach to architectural design. This corresponding approach will be enunciated by a second narrative voice running throughout this paper, describing two projects – developed as a contribution to my design research practice - that constitute both an embodiment and an extension of the critical apparatus developing here.

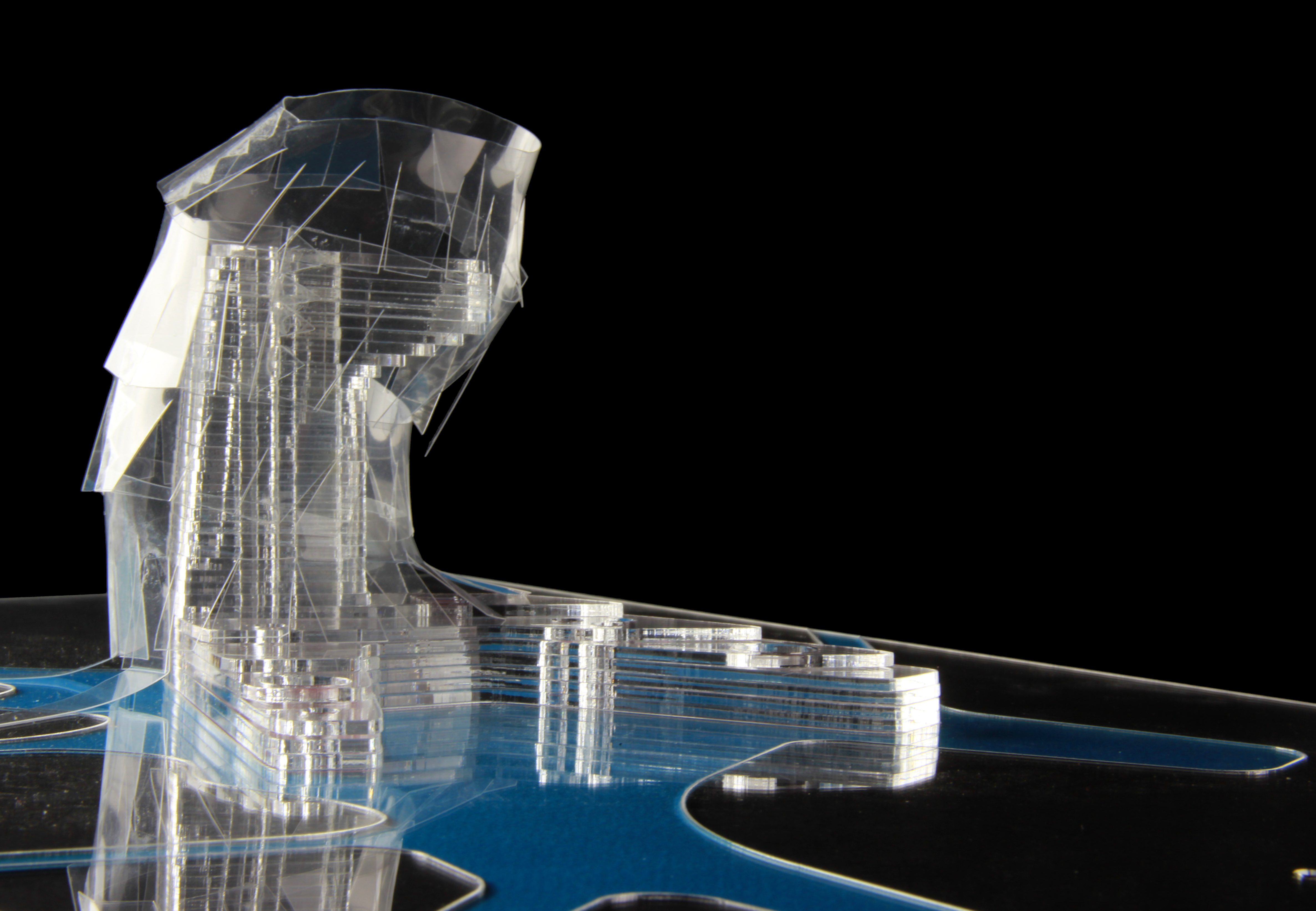

MEIAC enhanced environment is located in Badajoz in the south of Spain. Part of the Museo Extremeño e Iberoamericano de Arte Contemporáneo (MEIAC), it is a project for a device that uses the physical activity of climbing as a means for the public to interact with a number of digital art pieces loaned by the museum. In this scenario, digital art contents are displayed, perceived and explained as an integrated part of a broader physical and spatial environment.

Formally MEIAC enhanced environment is a hybrid assembly of material content and digital information, which articulates a dispersed, immersive atmospheric environment. It is organised around two complementary components: a hard node operating as a physical, tectonic base, and a soft node acting as an intermediate membrane that dynamically negotiates the limits between the hard node, the intermediate experiential environment and the outer atmosphere. Digital media content is released in the hard node, only to be captured again by the soft node, whose task is to delay its inevitable dissipation and make the digital piece incarnate as a physical body, subsequently articulating it as a component of a curated atmospheric environment.

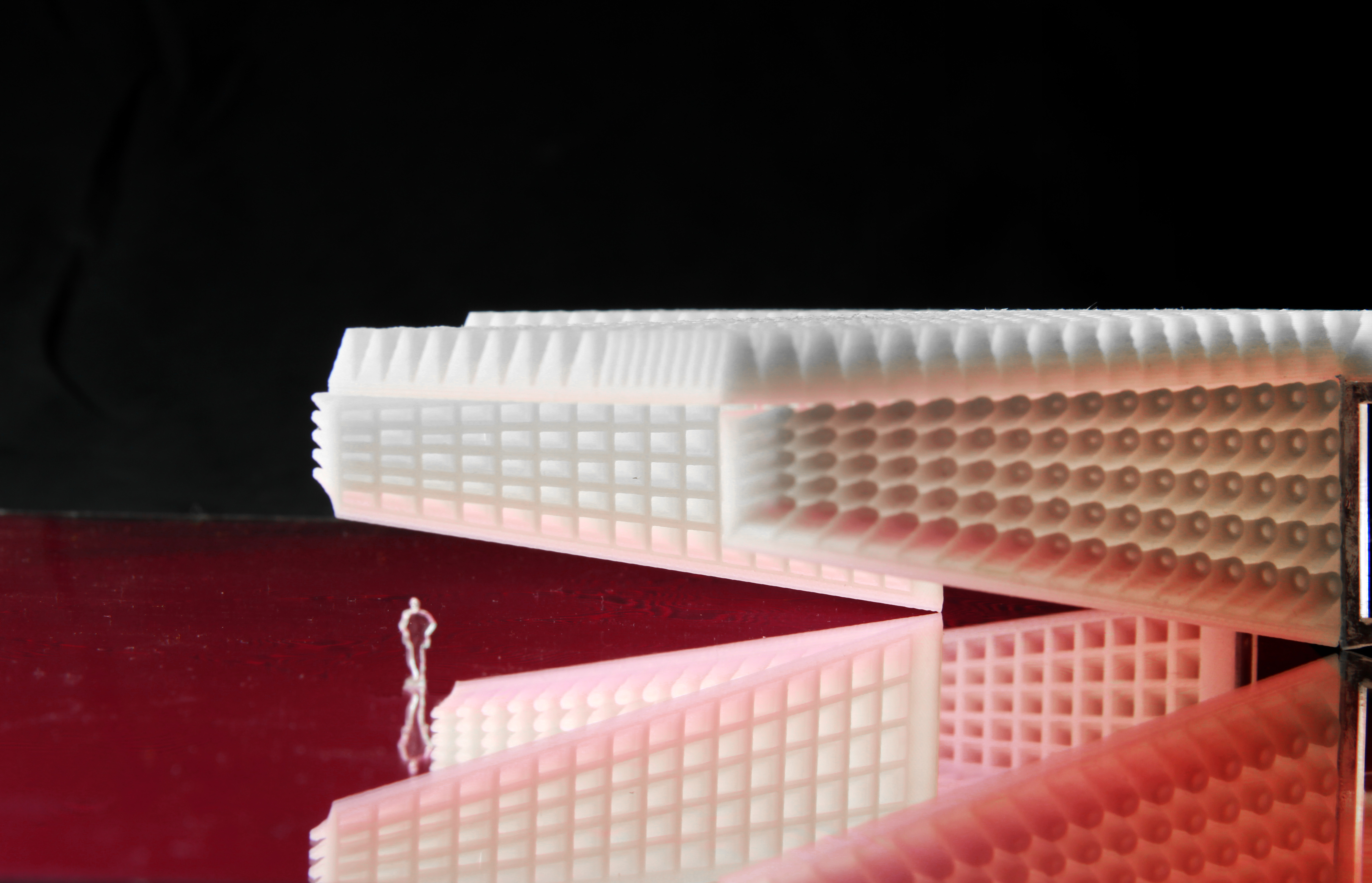

A second project, Doodle Earth, began with research on non-mechanical atmospheric conditions, to explore the production of environmental effects by the simplest means possible. It is deliberately abstract and unreferenced; it can be situated in different geographical locations, subtly modifying, amplifying or distorting the visual qualities of its surroundings.

Doodle Earth blends with its surroundings as a juxtaposed, textured visual layer, offering a dynamic range of perceptive experiences that suggest a certain blurring of its formal limits according to the position and the disposition of the viewing public. It is an unashamedly phenomenological device that subverts the established relationship between form (object) and background (context). It operates at the perceptive level by means of apparently contradictory operations such as signalling, specular imaging, vanishing, camouflage, and reversibility.

Usefulness and the Subjective Accrual of Value

The basic, recurring conditions that any work of architecture must fulfil in order receive positive reviews frequently gravitate around the notion of usefulness. However, if questioned, it is unlikely that a given architect or critic will be able to precisely determine what they understand as ‘useful’, or what the implications of the useful are for the formal or organizational qualities of a piece of architecture. Despite this uncertainty there appears to be universal consensus on the appreciation of the use-value of any given product or project, above any other consideration. The things that surround us have to do the job, to serve a purpose; extracting the maximum degree of performance becomes paramount. However, when examined in depth this propensity to utility simply indicates a socially constructed norm based on a simple binary opposition, a norm that in turn conceals the social mechanisms that govern the relationship of any given object with both the fulfilment of a given function and the accrual of value. In what follows I will endeavour to discuss this ‘norm’, what I term the ‘limits of the useful’, and the implications of social conventions of utility to architecture, to architectural production and design. I will also look at the implications of such social conventions for the associated ‘limit of the useless’, which the ‘norm’ described above sanctions as something of little value, something devoid of its own reason for being.As this paper locates itself within the context of architectural production and utility a consideration of what is perhaps the most enduring formulation of the useful in such a disciplinary context is unavoidable, namely the Vitruvian trinity of firmitas, utilitas, and venustas.[01] Consulting Vitruvius’ De Architecturawe notice that usefulness in a building is achieved through the convergence of two different conditions: disposition and decorum. The first condition is dependent upon the correct placement, dimensioning and orientation of the parts of the building.[02] As such, this condition implies the existence of an organization that is “composed,” that is, arranged as a series of parts within a hierarchical framework. The second condition, the implementation of decorum (from the Latin meaning: right or proper), suggests an underlying concern for the ‘appropriateness’ of the configuration of the building, in the sense that the use of each part can be perceived unambiguously and easily brought into correspondence with the whole.[03] In other words, Vitruvius’ utilitas denotes a hierarchical, univocal assembly of space and function.

Bernard Tschumi offers an interesting interpretation of the term utilitas. Tschumi translates utilitas as “appropriate spatial accommodation” in order to stress that the fundamental relationship being examined in Virtuvius’ description was that of the organization of space and the function to be fulfilled.[04] As Tschumi points out in Architecture and limits, such a binary relationship is problematic as neither the configuration of a given space nor the function to be fulfilled may necessarily be fixed, therefore any potential evaluation of appropriateness precludes consideration of the passing of time. For Tschumi, in contrast, the ever-changing interaction of space and body – an interaction giving rise to what he called ‘events’ as opposed to ‘program’ – constitutes an opportunity to build a framework of evaluation that supersedes this fixed relationship between space and function.[05]

Both MEIAC enhanced environment and Doodle Earth employ mechanisms to articulate a deliberately ambiguous relationship between their respective functions and spatial arrangements. Neither build on the static spatial and functional frameworks of Vitruvius’ utilitas; both proposals are closer to the oscillatory character of Tchumi’s event spaces. In MEIAC enhanced environment this ambiguity is achieved by dissolving the boundaries of functional areas while simultaneously emphasizing the formal outline of the base on which they are laid out. The spatial distribution of activities such as climbing, bouldering, resting or playing is replaced by a complex arrangement of physical properties related to texture, light, ventilation and humidity. Projectors, speakers and water sprinklers become both the regulators and the distributors of activity.

In contrast Doodle Earth directly taps into Brian Eno´s definition of ‘ambient’: a layer of information that is situated within an existing background and can be perceived at different levels of attention.[06] In this sense, and since the functional intent of this project revolves around perception, ambiguity is achieved by displacing various layers of optical signals from the foreground to the background (and vice versa) of the space as immediately perceived.

Whereas Tschumi’s reflections on oscillatory occupation offer an interesting starting point for identifying challenges to the space-function equation, and therefore for challenging conventional notions of usefulness, a question left unaddressed by Tschumi concerns the evaluation of such oscillations. In this sense, Marxist theory has produced a compelling narrative of value and its relationship with different modalities of use. From the Marxist point of view there is a binary distinction between use-value (the expenditure of all production efforts towards something that is used to its fullest extent, or its fullest consumption) and exchange value (the measure up to which something withholds the fulfilment of its function, becoming a means of exchange or a commodity). As Giorgio Agamben clearly notes, Marx considers that the enjoyment of use-value is opposed to the accumulation of exchange value as something natural is opposed to something aberrant.[07] From the perspective of architecture this opposition would suggest that use-value – a ‘positive’ value in Marxist rhetoric - would be exclusively accrued through situations in which the alignment of space and function is both complete and permanently activated. This view again brings up the passage of time as a key concern, but its shortcomings become obvious as soon as the relationship of space and function stops being considered as fixed.

01. Soft and hard nodes: initial membrane studies. MEIAC Enhanced Environment.

Value Beyond Classic Utility: The Obsolete, The Dysfunctional and The Dissipative

To summarise: of use and value Tschumi and Agamben seem to be asking (in architectural terms): does (programmatic) persistence, consistency, endurance, etc. grant validity or usefulness (to architecture)? Or, in other words: can alternative forms of value emerge from models that challenge persistence or continuity (of space and function)? Answering this question fully is beyond the scope and the length of this paper. However, it is possible to outline at least three different approaches that challenge socially sanctioned notions of usefulness by exploiting the possibilities of specific organizational frameworks and substantially altering conventional relationships of space, function and time. It must be noted that the approaches below do not attempt to constitute an exhaustive list, but rather suggest a series of possible starting points for the exploration of value and use in architecture.The first approach I would like to put forward is a mechanism for re-thinking utility through obsolescence and re-processing. The obsolete is concerned with those objects that can no longer fulfil the function they were initially designed to perform, and, if we limit this to the disciplinary framework of architecture, in the terms outlined above it essentially signals a misalignment of space and function. Most importantly here, what a mechanism for re-thinking utility through obsolescence might emphasize is the fact that the ‘obsolete’ space itself does not undergo any changes, rather it is the function to be fulfilled that is, for one reason or another, fundamentally transformed. Following this argument through there exists the opportunity to realign any given obsolete space, assuming new functions can be assigned to it.

Peter Eisenman set out (perhaps unintentionally) a compelling position on the obsolete in his 1976 editorial for ‘Oppositions’.[08] Here, Eisenman suggested that the relationship of an object to its function – which was expressed in architecture as an oscillation of function (or program) and form (or type as a manifestation of an ideal theme) – was, in fact, a fundamental construction of the humanist project. In this paper Eisenman argues that both terms, function and form, were traditionally invested with a certain value corresponding to the relationship of man and objects, and that until the advent of modernist sensibility the balance of the two terms was maintained . With the emergence of post-humanism society’s attitude toward the objects of the physical world changed, objects were no longer seen as having humanity as their originating agent. Reading Eisenman’s line of argumentation as a way of describing the mechanism of obsolescence we might say that in this post-humanist framework objects become independent – that is to say, detached from the human individual agent that historically constructed and articulated the balance between their form and their function. In this sense, obsolete space can be identified as autonomous precisely because it has been liberated from the pressure of functional constraints. In other words, obsolete space circumvents the Marxist duality of use-value and commodity-value by refusing to become either one or the other. It may abandon any formal engagement with function or – if entering into the realm of the reprocessed – shift between various, often contradictory functional relationships.

It is interesting to note how MEIAC enhanced environment can be regarded as a device that exploits a very interesting paradox concerning the distribution of digital content. Whereas a defining trait of digital material is the potential for wide-reaching, immediate dissemination beyond physical boundaries, the act of ‘slowing down’ this material by storing it in a museum collection can only be regarded as a perplexing move, effectively turning digital matter into a commodity. MEIAC enhanced environment attempts to counterbalance this commodification by re-mobilizing the digital material, reprocessing it by means of energetic dissipation. In this way digital content comes to be understood as a form of energy to be given away, a key component of a loosely orchestrated sensorial experience. The soft, titillating membrane that surrounds the upper areas of the base thus constitutes a blurry filter that captures the process of digital dissemination in both a visual and a haptic manner.

A second approach to re-thinking usefulness is represented by the dysfunctional, which, as the obsolete, emerges from a temporal misalignment of space and function. However, and unlike the case of the obsolete, in the dysfunctional it is space that is transformed in a way that renders it unable to fulfil the function it was designed for, while the function itself remains unaltered. If we reconsider Tschumi’s previous oscillatory framework in this light we can argue that in becoming dysfunctional the architectural object progressively moves towards a condition of deliberate refusal – or hesitation – to fulfil its function as expected.

Here, Giorgio Agamben’s ideas can be brought back into focus, particularly those dealing with what he denominates “a bad conscience with respect to objects.”[09] Agamben approaches the question of post-humanism in a fundamentally different manner to Eisenman. He describes a reality in which objects – having been detached from human possession through mass production – refuse to perform their duties, literally rebelling against their users with a kind of deliberate perfidy. Here what is relevant to rethinking usefulness through the dysfunctional, as Agamben points out, is that once these refusals are pushed to their limits it is possible to escape the dichotomy of use-value and commodity as defined by Marxist rhetoric, effectively entering into a third state that would restore the object to its own truth, disengaged from any relationship of use with human beings. To again apply this line of reasoning to architectural production, this possibility suggests the radical abolition of any kind of subjectivity from space itself, particularly subjectivity as it relates to function. For Agamben this abolition is triggered by the exaggeration of the irrelevant, an extreme elevation of the object beyond any kind of practical purpose. This is, Agamben suggests, the mechanism through which ‘dandies’ operate.[10] Whereas in architectural terms this ‘exaggeration of the irrelevant’ could be regarded as a simple fixation with the ornamental, a more insightful reading of this mechanism would be to think of ‘irrelevance’ as a permanent resistance to considering any kind of practical purpose as an objective element in evaluating architectural space. In this light, as in the case of the obsolete, the most important consequence of the dysfunctional is the emergence of a promisingly promiscuous, oscillatory relationship with use, in which the commitment to a single function is impossible, but flirtation with multiple human subjectivities is encouraged.

As an incarnation of the dysfunctional, Doodle Earth is a radical refusal to construct any univocal mechanism for coupling form and function. In a similar manner to Agamben’s dandies, this is achieved through an extreme exaggeration of the contradictory forces that articulate the project. Doodle Earth presents us with an interior space that captures its surroundings and transforms their properties into an abstract, rhythmic perceptive layer. This interior is coupled with an exterior that blends into its surroundings and simultaneously emphasizes them by subtly signalling their properties. The cross-shaped outline of the proposal defines a certain spatial alignment, and also marks a spot where the intensity of the perceptive layer as a juxtaposition to the surrounding environment reaches its climax. As a result of these operations, the experiences of the interior and the exterior become blurred and indistinct while, simultaneously, oscillating between the strict definitions and markings of a clear geometric framework, and the dissolution of that framework. Thus, dissolution and geometry are intertwined to constitute a dysfunctional mechanism of radical, perpetual contradiction.

The third and final approach that I will introduce here reconsiders the value of the useful in architecture through dissipation, which taps directly into Georges Bataille’s theory of ‘General Economy’. Bataille argued that for any effort to be considered valid in contemporary society it must be reducible to the satisfaction of the needs of a closed economy of production and conservation (a cycle in which any productive surplus is immediately fed into new productive activities). For Bataille this means that any operations not oriented towards growth – such as pleasure, luxury or any permanent expenditure – effectively become subsidiary, and therefore the artistic, the monumental or the spectacular are reduced to the status of ancillary practices.[11]

However, it is precisely this mechanism of expenditure or non-productive consumption – the theoretically useless side of human activity – that Bataille considered a counterbalancing factor to the potentially catastrophic effects deriving from unlimited accumulation and growth. In this sense, Bataille identified the construction (and also the destruction) of architectural objects such as cathedrals – luxurious, enormous and devoid of accumulative purposes – as efforts fundamentally oriented to the development of a sense of meaning through an orchestrated consumption of resources; these projects constitute escape valves to counterbalance contemporary systems of accumulation.

Following Bataille’s arguments, glorious operations – operations that accrue social value by means of wasteful spending or dissipation – can be understood as a complementary system of actions to those operations oriented towards optimized production. As Denis Hollier points out,[12] and as in the previous two approaches to rethinking the useful, Bataille’s view challenges the binary approach of Marxist rhetoric by considering the passing of time as a tool to articulate the alternating rhythms of production and expenditure rather than as a tactic to defer consumption with the sole purpose of accumulating exchange value. As an integral part of his efforts to explore the revolutionary potential of architecture, Bernard Tschumi mobilized Bataille’s notion of expenditure in the form of a number of architectural interventions. The most relevant intervention in this context was ´Fireworks´,[13] which was simultaneously a wasteful, spectacular ‘event’ – as it could be denominated using Tschumi’s own taxonomy – and a manifesto in which Tschumi boldly stated that architecture must be built and burned just for pleasure.[14]

Both MEIAC enhanced environment and Doodle Earth attempt to mobilize the notion of expenditure within an architectural framework. MEIAC enhanced environment is articulated around two forms of expenditure: one of human energy – the state of physical exhaustion induced by climbing to the top of the base is the preferred, hallucinatory form of perceptive disposition – and one of digital content – which is continuously and deliberately expelled from the system. These mechanisms generate an oscillating perceptual layer that puts the digital in relationship with the body by slowing down its release or, in other words, by increasing its viscosity. By disseminating content at an intermediate speed – neither immediate consumption nor commodification – this proposal attempts to resist entering into a binary discourse of production and conservation.

In Doodle Earth the experience of the exterior is dissolved into the interior in an almost pointillist fashion. Form and shape are transformed into a dynamic range, a chromatic gradient that stretches along the ‘arms’ of the volume. The ultra-reflective nature of its architecture ensures light – as a form of optical energy – is simultaneously captured and released in a filtered capacity. Light is, therefore, spent as soon as it enters the system. Movement across the interior offers an experience of continuous perceptive variation as the gradation of light, shadow, colour and tone changes according to the position of the spectator. In turn, the immediate surroundings receive back a filtered, distorted, fragmented version of their own optical properties.

It must be noted here that considering expenditure as a counterbalance to utilitarian or productive mechanisms has proven to be problematic. Bataille himself expressed the difficulties of his position in his introduction to The Accursed Share,[15] but perhaps a more clear account of the contradictions inherent in his theory can be found in Geoffrey Bennington’s writings.[16] As Bennington summarizes, expenditure as a challenge to the useful is paradoxical insofar as its counterbalancing effect is, in fact, highly functional. I would acknowledge here that this critique can easily be extended to the discussions of the obsolete and the dysfunctional as mechanisms for challenging utility as described above since, as mechanisms of reaction to a specific understanding of the useful, they automatically become useful. However, it can be argued that this is only an apparent contradiction, one which is derived from considering usefulness as a closed category strictly circumscribed to the configurations of space, function and time represented by Vitruvius’ utilitas. According to such a view, the obsolete, the dysfunctional and the dissipative can only be articulated as mechanisms against the useful, and therefore as representations of uselessness. If, on the contrary, we move away from this strictly binary representation of the useful and the useless, it becomes possible to understand usefulness as a range of variation in the relationships of space, function and time, and Vitruvius’ utilitas as nothing more than a particular position within this range. Consequently, the obsolete, the dysfunctional and the dissipative would not need to be defined as ‘opposed to’ the useful, but rather as ‘departing from’ the position represented by Vitruvius’ utilitas. Hence, a suitable response to the implications of Bennington’s critique would be that this piece does not discuss the opposition of utility and uselessness, but rather attempts to unveil the full range of positions that exist between the limits of usefulness.

02. Study of mirroring and colour dispersal. Doodle Earth.

Beyond the Binary Model: Phase Space as a Multidimensional Range of Oscillation

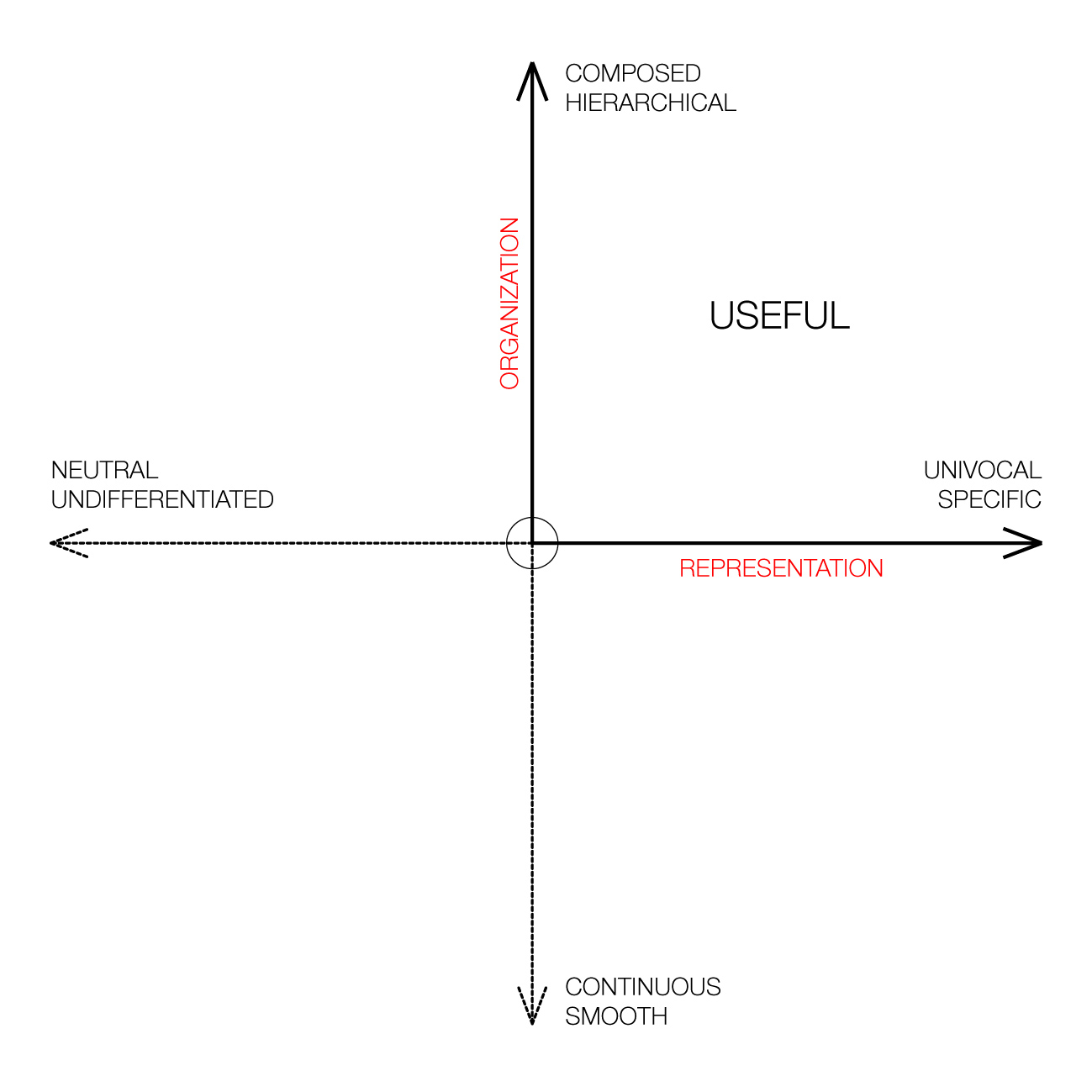

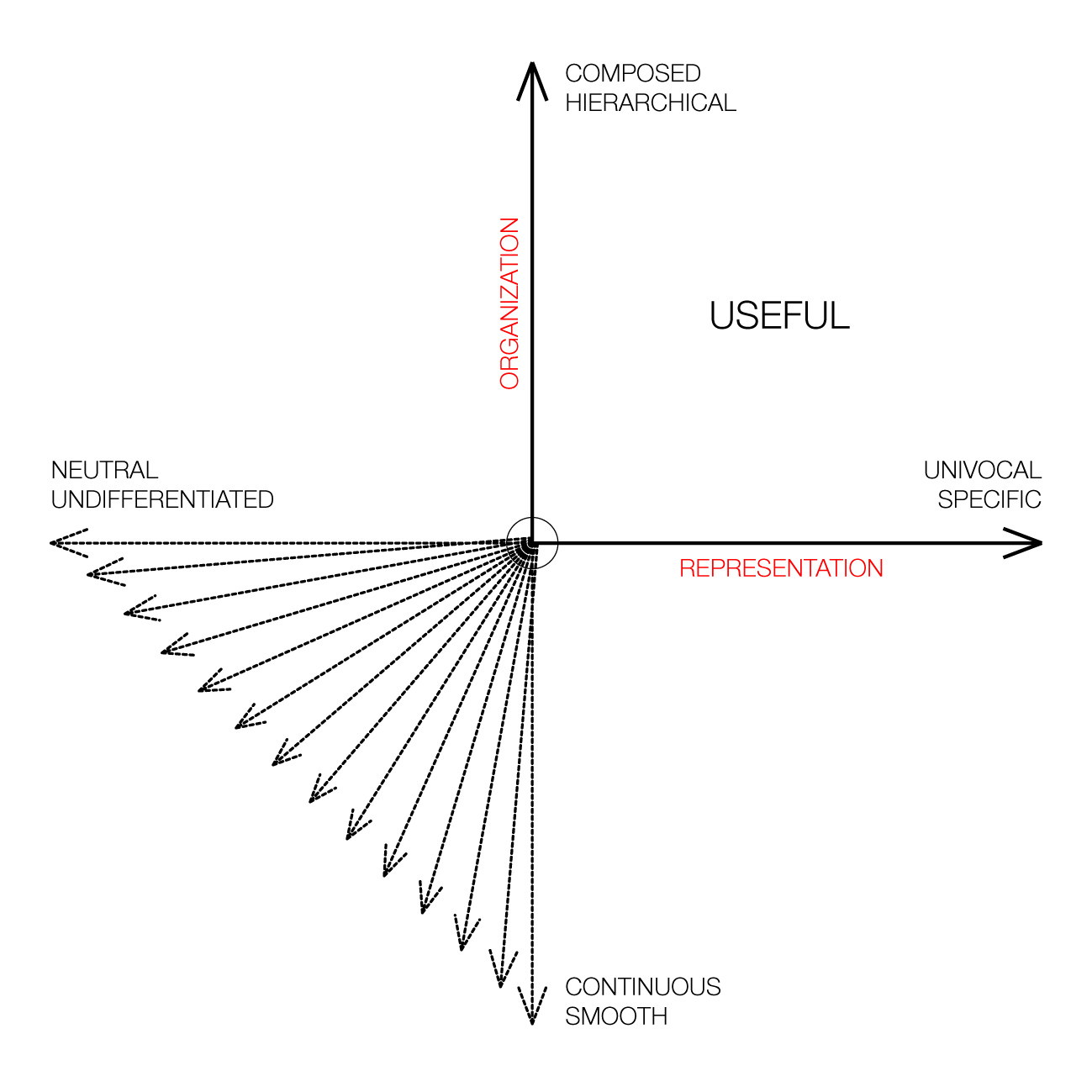

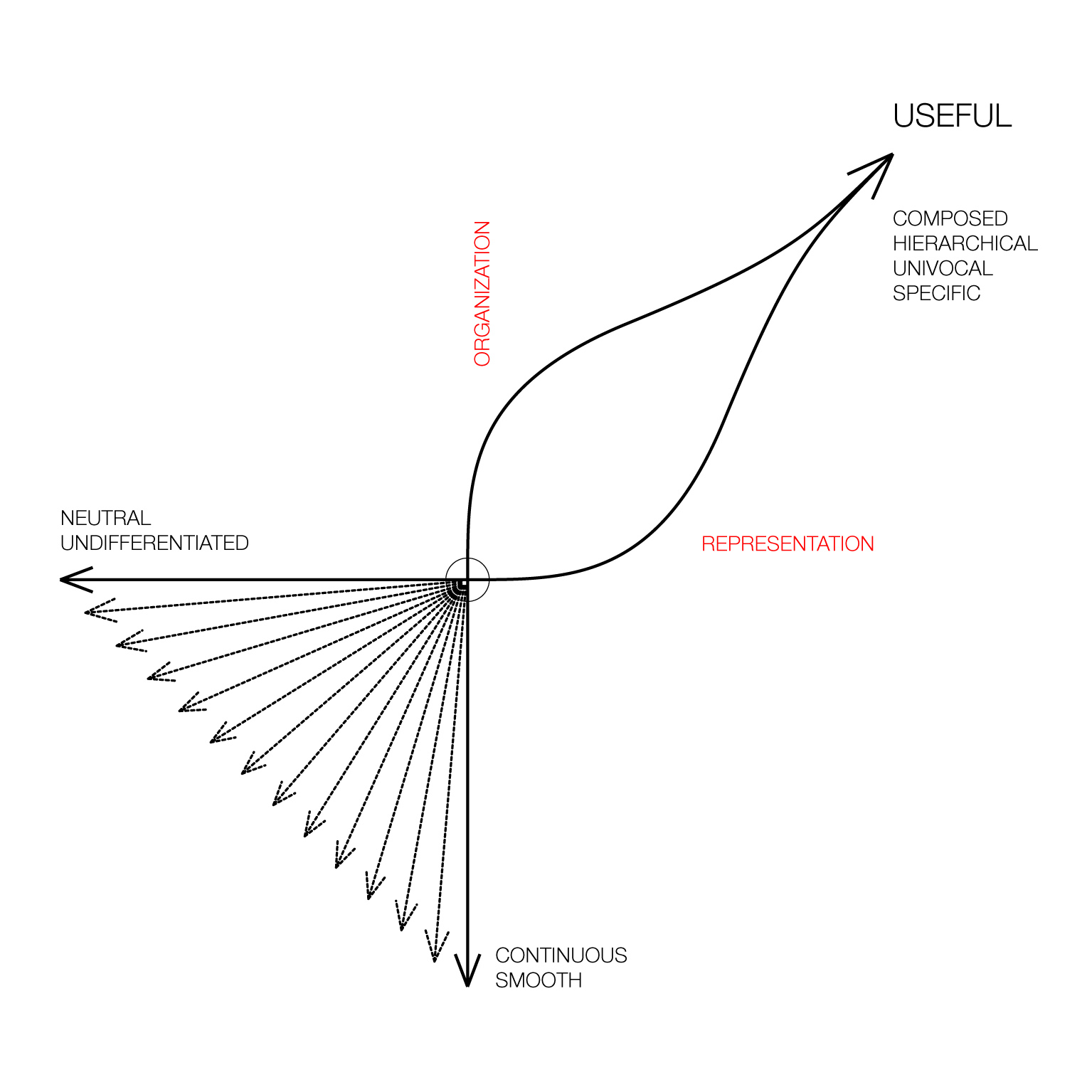

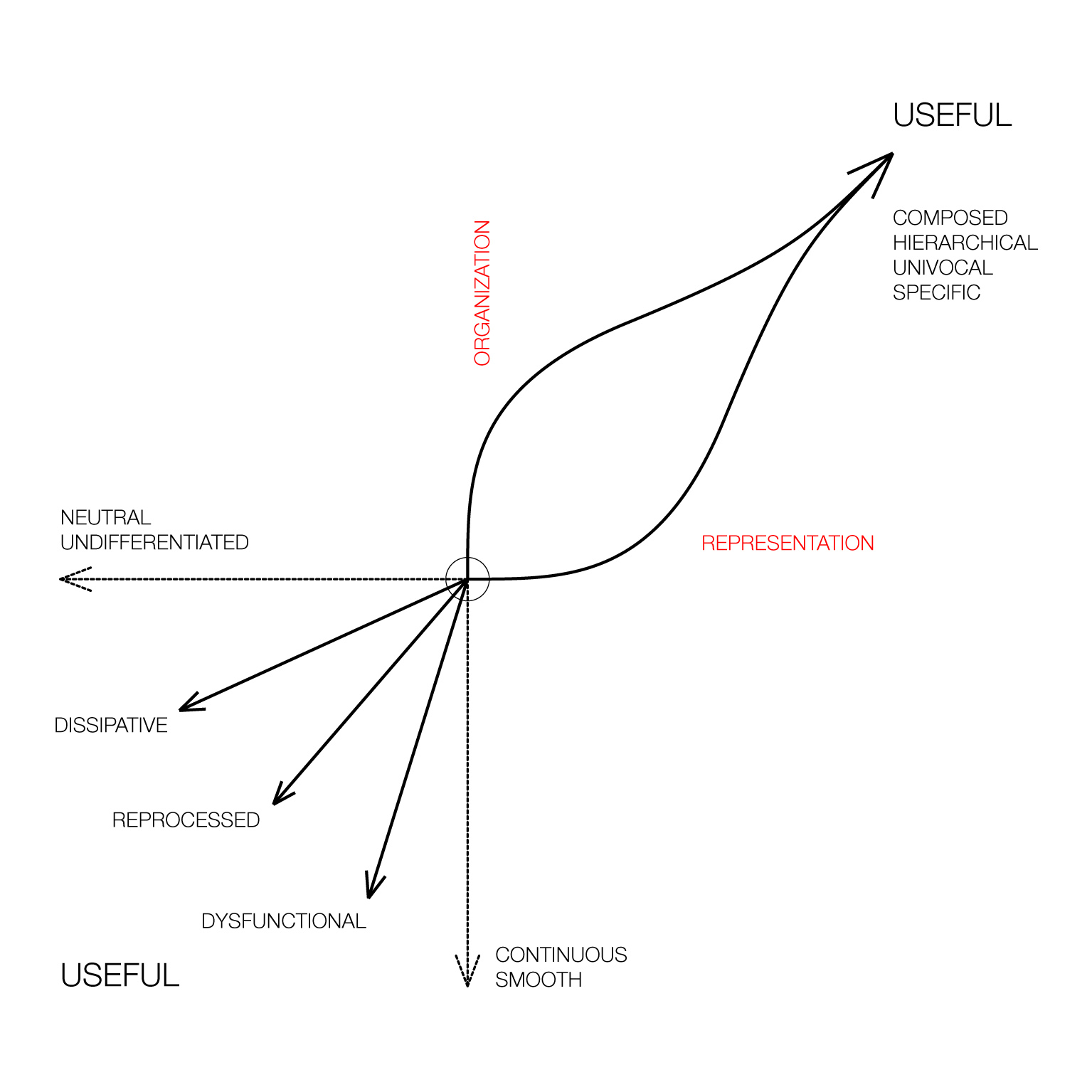

As an alternative to the useful-useless binary model described above this paper taps into the methodological approach presented by philosopher Manuel de Landa in his multiple, neo-materialist readings of the work of Gilles Deleuze. Following Deleuze, De Landa argues that in defining the conditions of a problem rather than attempting to solve it we are effectively modelling the space of its possible solutions.[17] De Landa´s ‘modelling’ approach assumes that both the conditions of the problem and its solution define multidimensional intervals or phase spaces, rather than a series of linear operations. These intervals are defined by those states in which constraints enforced by the problem are fulfilled, and, therefore, they constitute spaces of variation containing all the solutions of a given problem.[18] If we consider the question of usefulness in this manner we can begin to understand usefulness as a space of dynamic oscillation between differing tendencies rather than as a quality that is either present or not present. For the sake of clarity such a space can be illustrated as a two-dimensional plane whose coordinates are defined by organizational and representational tendencies. In this model, the coordinate axes representing both the tendency towards a composed, hierarchical organization of parts and the tendency towards specificity and the univocal orientation of function can be pictured as deformed to converge into an asymptotic line that represents the conditions of Vitruvius’ utilitas. This state, understood as one of the boundaries of the phase space we are attempting to model, would therefore constitute one of the limits of the useful after which this paper is titled.Organizational and representational trajectories moving in the opposite direction along these coordinate axes would define the other limits of this phase space. We could understand these trajectories as lines of flight or lines of departure in Deleuze and Guattari’s terms, which break away from the static character of Vitruvius’ utilitas.[19] The most immediate consequence of this conceptual model is the emergence of a space between the limits of the different tendencies of the useful. It can easily be argued that most architectural works could be positioned somewhere within this space, leaning towards one limit or another according to their organizational and representational qualities. We could also add that, rather than the specific position of a specific object, the relevant scale of operation in this scenario would be determined by the general tendencies or trajectories conveyed by a given approach to design as defined by its associated outcomes.

Within this model the obsolete, the dysfunctional and the dissipative can be identified as three examples extracted from an infinite array of lines of departure from the asymptotic limit defined by static, hierarchical and univocal usefulness. Design tactics in which the qualities associated with these departure mechanisms are pushed to an extreme can therefore be regarded as approaching the other limits of the useful. As our design practice approaches these limits, functional organization – understood as a univocal, static pairing of space and function – becomes less and less relevant in articulating the design argument.

The Expanded Field of Usefulness

This paper introduces a conceptual framework in which the useful is not an absolute category, but rather a multidimensional range of positions concerning the relationships established by space, function and time. In so doing its ambition is to open up a productive discussion on how certain works of architecture – such as the proposals presented alongside this text – can be evaluated outside a conventional framework of usefulness that relies on a direct, univocal relationship between spatial arrangement and functional performance. By articulating an expanded conceptual field that challenges the binary categorization of the useful and the useless we may recover for the discipline of architecture the operational agility of a number of mechanisms that are socially tainted by a prevailing distaste for frivolity. Far from being frivolous, these mechanisms – the obsolete, the dysfunctional, the dissipative, and many other still uncharted lines of departure from a conventional approach to the useful – constitute a very serious opportunity to construct a necessary counterbalance to contemporary positions in architectural discourse that seem to concern themselves exclusively with issues of performance, optimization, conservation and streamlining.

03. Diagramming the Useful: The useful depicted as phase space; Lines of departure from Vitruvius’ notion of utilitas; Vitruvius’ notion of utilitas as an asymptotic line in phase space; The obsolete/reprocessed, the dysfunctional and the dissipative as possible lines of departure from a static notion of usefulness.

Published 24th September, 2015.

Notes

[01] Further references to Vitruvius’ work in this paper are taken from Frank Granger’s translation of De Architectura, which is edited from Harleian manuscript 2767, dating from around the first quarter of the ninth century, the oldest extant copy of this treatise. It is therefore considered to be a relatively close approximation to Vitruvius’s original intent.

[02] “…when the sites are arranged without mistake and impediment to their use, and a fit and convenient disposition for the aspect of each kind.” Virtuvius, Pollio M. 1931. On Architecture: Edited from the Harleian Manuscript 2767. Trans. Frank Granger. London: W. Heinemann, Book I, Chapter III, p. 35.

[03] “…the fit assemblage of details, and, arising from this assemblage, the elegant effect of the work and its dimensions, along with a certain quality or character.” Vitruvius, Pollio M. 1931. On Architecture, Book I, Chapter II, p.25.

[04] Tschumi, Bernard. 1994. “Architecture and Limits,” in Tschumi, Bernard. 1994. Architecture and disjunction. Boston: MIT Press, pp.102–118.

[05] Tschumi, Bernard. 1994. “Architecture and Limits,” pp.102-118.

[06] Eno, Brian. Ambient Music. 1978. Liner notes of “Music for Airports / Ambient 1”, PVC 7908 (AMB 001).

[07] See: Agamben, Giorgio. 1993. “Beau Brummell; or, The Appropriation of Unreality,” in Agamben, Giorgio. 1993. Stanzas: Word and Phantasm in Western Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 47–55.

[08] Eisenman, Peter. 1976. “‘Post-Functionalism’, Oppositions, Vol.6 (Fall 1976),” in K. Michael Hays (ed). 1998. Architecture Theory since 1968. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, pp.236-239.

[09] Agamben, Giorgio. 1993. “Beau Brummell; or, The Appropriation of Unreality,” pp. 47–48.

[10] Agamben, Giorgio. 1993. “Beau Brummell; or, The Appropriation of Unreality,” pp. 48. In Agamben’s own words, the ‘dandy’ is “the man who is never ill at ease,” making “of elegance and the superfluous his raison d’etre.” In so doing, Agamben continues, the ‘dandy’ “teaches the possibility of a new relation to things, which goes beyond both the enjoyment of their use-value and the accumulation of their exchange value.”

[11] Bataille, Georges. 1984. “The Notion of Expenditure,” in Allan Stoeckl (ed.). Visions of excess: selected writings 1927-1939. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 116–129.

[12] Hollier, Denis. 1992. “The Use-Value of the Impossible,” trans. Liesl Ollman. October, Vol.60, pp.3–24.

[13] Martin, Louis. 1990. “Transpositions: On the Intellectual Origins of Tschumi’s Architectural Theory,” in Assemblage, No.11 (April), pp.23–35.

[14] “Yes, just as all the erotic forces contained in your movement have been consumed for nothing, architecture must be conceived, erected, and burned in vain. The greatest architecture of all is the fireworker’s: it perfectly shows the gratuitous consumption of pleasure..” Tschumi, Bernard and Goldberg, RoseLee. 1975. A Space, a Thousand Words. London: Dieci Libri, no page number.

[15] “In other terms, my work tended first of all to increase the sum of human resources, but its results taught me that accumulation was merely a delay, a retreat before the inevitable outcome, in which accumulated wealth has value only instantaneously. Writing the book in which I said that energy can in the end only be wasted, I myself was using my energy, my time, my labor: my research responded in a fundamental way to the desire to increase the sum of goods acquired for humanity. Shall I say that in these conditions I could sometimes do no other than respond to the truth of my book and could not continue writing it?” Bataille, Georges. 1991. The Accursed Share: An Essay on General Economy. New York: Zone Books, pp. 10.

[16] Bennington, Geoffrey. 1995. “Introduction to Economics I: Because the World Is Round,” in Carolyn Bailey Gill (ed.). 1995. Bataille: Writing the Sacred. London: Routledge, pp. 46–57.

[17] De Landa, Manuel. 2010. Deleuze, History and Science. New York: Atropos Press, p.151.

[18] De Landa, Manuel. 2010. Deleuze, History and Science, pp.142-144.

[19] Deleuze, Gilles and Guattari, Félix, 1987. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp.9-10.

Figures

Banner.

Plan drawing. MEIAC Enhanced Environment. Miguel Paredes Maldonado.

01.

Soft and hard nodes: initial membrane studies. MEIAC Enhanced Environment. Model and Photograph: Miguel Paredes Maldonado.

Soft and hard nodes: initial membrane studies. MEIAC Enhanced Environment. Model and Photograph: Miguel Paredes Maldonado.

02.

Study of mirroring and colour dispersal. Doodle Earth. Model and Photograph: Miguel Paredes Maldonado.

Study of mirroring and colour dispersal. Doodle Earth. Model and Photograph: Miguel Paredes Maldonado.

03.

Diagramming the Useful. Miguel Paredes Maldonado.

Diagramming the Useful. Miguel Paredes Maldonado.

https://doi.org/10.2218/z9tbw063