Pause: A Device for Troubling Routines

Sepideh Karami

It’s June 2013. I’m fiddling with my phone, scrolling up and down the pages. The Occupy Gezi movement is still underway in Turkey, despite the park being evacuated by police and the imposition of a curfew banning the gathering of more than eight people. That an urban planning project – the takeover and demolition of the Gezi public park – has triggered such a movement demonstrates the on-going social resistance to the commercialisation of urban spaces, a resistance that is part of the constant struggle over the right to the city, or, in David Harvey’s terms, “a right to change ourselves by changing the city” as “the exercise of a collective power to reshape the processes of urbanization.”[01] However, while it is this resistance that is made manifest by the emergence of the Occupy Gezi movement, what I find fascinating is the offspring of the curfew: the new waves of passive protests that suggest that the movement has entered a new phase. The marker of this new phase is the appearance of the Standing Man.

On The Guardian blog on 20th June Kaya Genc (under the alluring title The standing man of Taksim Square: a latterday Bartleby) writes:

(…) a young man wearing a white shirt and grey trousers appeared in Istanbul’s Taksim Square. He walked towards Ataturk Cultural Centre, adjacent to the Gezi Park, which had turned into a battleground. But the young man didn’t go inside the park. Instead he stopped in front of the Cultural Centre, placed his backpack on the ground, put his hands in his pockets and stared at the building for eight hours.[02]

A clear message: instead of going to the park, which had turned into a battleground, this young man had come to the ‘wrong’ place but found it the ‘right’ site for expressing disobedience or resistance. His body, fragile and vulnerable, standing alone in the middle of the square in front of the massive Ataturk Cultural Centre,[03] unsettled what had until then been called the “Occupy Gezi movement”. As civilian security officers search him it is clear that standing still has become a crime in Turkey, and simultaneously that a disarmed body standing in a public space can be threatening. While it seems unimaginable that silence or inactivity could be used as a weapon in an increasingly mobile, integrated, high-speed society, the standing man causes us to pause.

* * *

- “Pause is a technique for troubling routines, a tactical device for change capable of disturbing established flows. What comes out of this disturbance is, of course, contingent and unexpected, but it is critical to have an image of it. Metaphorically, it enhances the ‘stammering’ moment,[04] in Deleuze’s terms, the moment of dysfunction. Pause interrupts, but it also connects through new and undefined connections; this is the ‘infrastructural behaviour’ of the pause.”

- An interruption from the left corner of the lecture hall: “What do you consider ‘routines’?”

I continue:

- “Routines are established sequences of actions that allow the normal flow of everyday life to continue; they guarantee the familiar. By routines I mean the processes through which the wheel of capitalist production operates; through which commoditised everyday life moves; through which dominant systems, whether economic or ideological, are optimized; through which the dominant power is stabilised. Where urban public spaces are concerned, routines become the sum of all the flows and circulations of life that protect the order of those public spaces. In this context a pause is a device, an act, however tiny, that unsettles this balance or order, bringing about a moment of dysfunction where an individual is liberated for an unspecified duration. While the dominant power is busy ‘fixing’ this pause, alternatives can emerge.”

At the push of a button an image of an Israeli checkpoint emerges on screen. I continue:

- “There are always moments of compulsory pause in our everyday life: checkpoints, people waiting at traffic lights, traffic jams and queues. Needless to say, the liberating potential of pause cannot be found in these moments. On the contrary, these are pauses of control that belong to our daily routines. Similarly, there are pauses for consumption that favour the spectacular gaze. I differentiate these routine pauses from pauses of opposition and resistance, or pauses of transgression.”

* * *

[T]he moment has its specific negativity. It is destined to fail, it runs headlong towards failure.[08]

I read a few pages further and come to the conclusion that the pause of the Standing Man is likewise destined to fail, either as a result of the suppressive force of a dominant power or the biological limitations of the body. In either case it is the resistance to an inevitable failure that fascinates me, the tension between moving and standing. In this tension we might come to understand the efficacy of the pause, even as it is destined to fail. As Lefebvre notes: “If we are to understand and make a judgement, we must start not from the failure itself, but from the endeavour which leads to it.”[09] The pause, as an act of inevitable failure, must be understood as both moment and endeavour, and it is the moment of the failure of the pause, the liberation of an intense energy at the tragic moment when the pause ends, that is key. While the affectivity of the standing man as protest (the endeavour) is clear, the aftereffect of the pause is less readily grasped, but it is at this point that those dominant flows that existed prior to the pause are inexorably changed.

* * *

- “It definitely is,” I reply. “I believe one of the fundamental characteristics of pause as a device for change is duration. Pause disturbs power, but in such a way that it does not provoke an immediate reaction. It is an interruption rather than a disruption, and in this interruption there exist chances for an alternative to emerge. In fact, one of the contributions that architectural practice could make in working with pause would be to work with this duration – and to expand it.”

* * *

* * *

They show the fence from a distance, bodies piling up behind it, smothered, sometimes only fingers moving, and it is like a fresco in an old dark church, a crowded twisted vision of a rush to death as only a master of the age could paint it.[11]

I begin to see how the spaces between those surrounding the Standing Man create an expanded tissue of bodies that spreads over a territory. I feel an urge to zoom out and see the landscape created: the bodies as fixed points, the spaces as active connections, intensity present in the gaps, an infrastructure of bodies appended to the city. This landscape of connected but dispersed bodies threatens those in power.

01. Standing man, Occupy Gezi Movement, Istanbul, 2013. Still from YouTube video.

* * *

“What are you looking for?” I asked

“Trying to find myself dear. I was there every single day. I was one of the standing bodies there. And it matters that ‘I’ was there.” He replied.

* * *

02. Unfinished building, Liberty Street, Tehran during the 1979 Revolution. Still from A Dialogue with Revolution, 2013 [Film].

- “Are sit-down strikes a sort of pause?” another student asked from the first row.

- “Definitely” I answered. “They are a pause in the capitalist production instigated by factory owners; by refusing to work while being present productivity decreases and profits are reduced. So pause as a collective action is hugely detrimental to the proprietor.”

“I suspect what lies behind your question is that you are, in fact, wondering what the difference between these two forms of pause is? Or, what in particular the standing bodies produce that the strike does not? I would argue that the two both come from a politics of refusal and disobedience. They are similar in many ways: they are a way of claiming your rights by not participating, by not being part of a system, and they both act through the momentary appropriation of space, be it public space or the space of factory (production). Crucially both the strike and the standing man question routines. However the particular political situation within which the standing man ‘stands out’ (stands outside the norms of a public space) is key, this act concerns the politics of public space ‘as a medium allowing for the contestation of power’.”[12]

“For eight hours the standing man occupied Taksim Square, the main transportation hub in Istanbul and a historically and strategically important urban site. Today this square is a typical modern public space – a de-politicised neoliberal space of commerce, consumption and control; a “representation of space” in Lefebvre’s terms.[13] However, this is also a ‘representational space’. Or, in Hana Arendt’s terms, a ‘space of appearance’ where people, through their actions, become visible.[14] As Simon Springer notes, this interplay of visibility and action is critical:

While visibility is central to public space, theatricality is also required because whenever people gather, the space of appearance is not just ‘there’, but is actively (re)produced through recurring performances.[15]

Public space provides visibility to political action and encourages participation.[16] The standing bodies physically occupied public space and introduced a new infrastructure of bodies into the existing material urban infrastructure.”

* * *

“The question, ’what is [it] that we can do together?’ – whoever and wherever that ‘we’ may exist – is largely a question of what is in-between us; what enables us to reach toward or withdraw from each other. What is the materiality of this in-between – the composition and intensity of its durability, viscosity, visibility, and so forth? What is it that enables us to be held in place, to be witnessed, touched, avoided, scrutinised or secured? Infrastructure is about this in-between.”[17]

The infrastructural pose of the bodies is what keeps the crowd from being disbanded. The bodies connect and flow through infrastructures, but also perform as an infrastructure themselves. They make connections, fill in the in-between spaces, activate interstices, and transform the behaviour of the existing material infrastructure. Just as a material infrastructure they fix and distinguish points and spaces, but as they are in constant motion this fixity is more fluid. This infrastructural character is essential to the effective potential of pause to create change. Fragmented pauses can only perform as safety valves, creating critical moments instead of nurturing emergent politics, whereas an infrastructure of pauses, a connection of bodies across extended territories rather than a single standing man, takes on immediate political affectivity.

* * *

- “Firstly I would like to stress the importance of body politics to the idea of pause as a device. Describing the role of the body in disturbing the purity of architectural order, Bernard Tschumi notes that:

[T]here is the violence that all individuals inflict on spaces by their very presence, by their intrusion into the controlled order of architecture. Entering a building may be a delicate act, but it violates the balance of a precisely ordered geometry.[18]

So where pause as a device is concerned, perhaps it is primarily in the sense of a post-production of space by means of occupation. This is visible in the examples of the Standing Man and likewise in the building in Tehran in 1979. Therefore, to enhance the affectivity of a pause as a device for change and liberation we must consider the possible post-production occupation of space. It is therefore crucial to think further about what architecture can do to enhance the potential for pause.

Secondly, a pause is an event. Architecture should facilitate this event, creating spaces that can absorb and intensify those forces and elements that break with existing or routine flows. Here the architect’s ability to identify chances, to read the existing gaps in any system, and develop those gaps to the point where alternatives could emerge becomes key.

Maurizio Lazzarato describes the event as follows:

The event gives us an open, unfinished, and incomplete world, and in so doing calls upon subjectivity because we can inscribe our actions and exercise our responsibility in this incompleteness, in this non-finitude.[19]

The unfinished and incomplete; this describes the very aesthetics of infrastructural architecture; the infrastructure of pauses.”

I continue: “By way of an example we might consider how existing spaces already work as spaces of pause. Mohsen Mirdamadi, an architect and researcher working with urban issues within large cities in Iran, notes that in the high-speed spaces that we move through daily there is a need to stop. His term ‘Rahvand’, meaning ‘spaces attached to a route’, mimics an infrastructure of pauses.[21] He likens cities to the Silk Road, arguing that spaces like caravanserais or water reservoirs are not only spaces for resting, eating, trading, etc., rather they are, more importantly, social spaces where spontaneous encounters produce new conditions along the road. Rahvands are spaces of speculation and reflection after moving and traveling; a pause that is not an end to the moving, but a point of departure enriched by encounter. Similarly, a city consists of spaces of moving and pausing. What enriches the political and social life of the city is not the roads but the “pause spaces” that make up the sequences of social life. At political and social turning points where large numbers of people gather, they do so in pause spaces, either found or invented by their own action. This means that many of these spaces are not designed as pause spaces but are capable of being inhabited and activated through different sorts of occupation.

* * *

a solid of a gap between spaces. The gap thus becomes a space of its own, a corridor, threshold, or doorstep – a proper symbol inserted between each event.[22]

Thinking of pause spaces in this way means that as well as those ‘un-designed’ spaces of event, we might consider architecture’s role as identifying chances or in-between sequences, expanding them and creating new alternative inter-sequences. The revelation of a previously undefined space along a familiar and defined space of flow could stimulate a pause in that flow. Revealing it, however, cannot always be done by architecture alone in its established form. This is perhaps where architecture should pause, refrain from meddling with space; pause to reflect upon a fetish for completing the world.

* * *

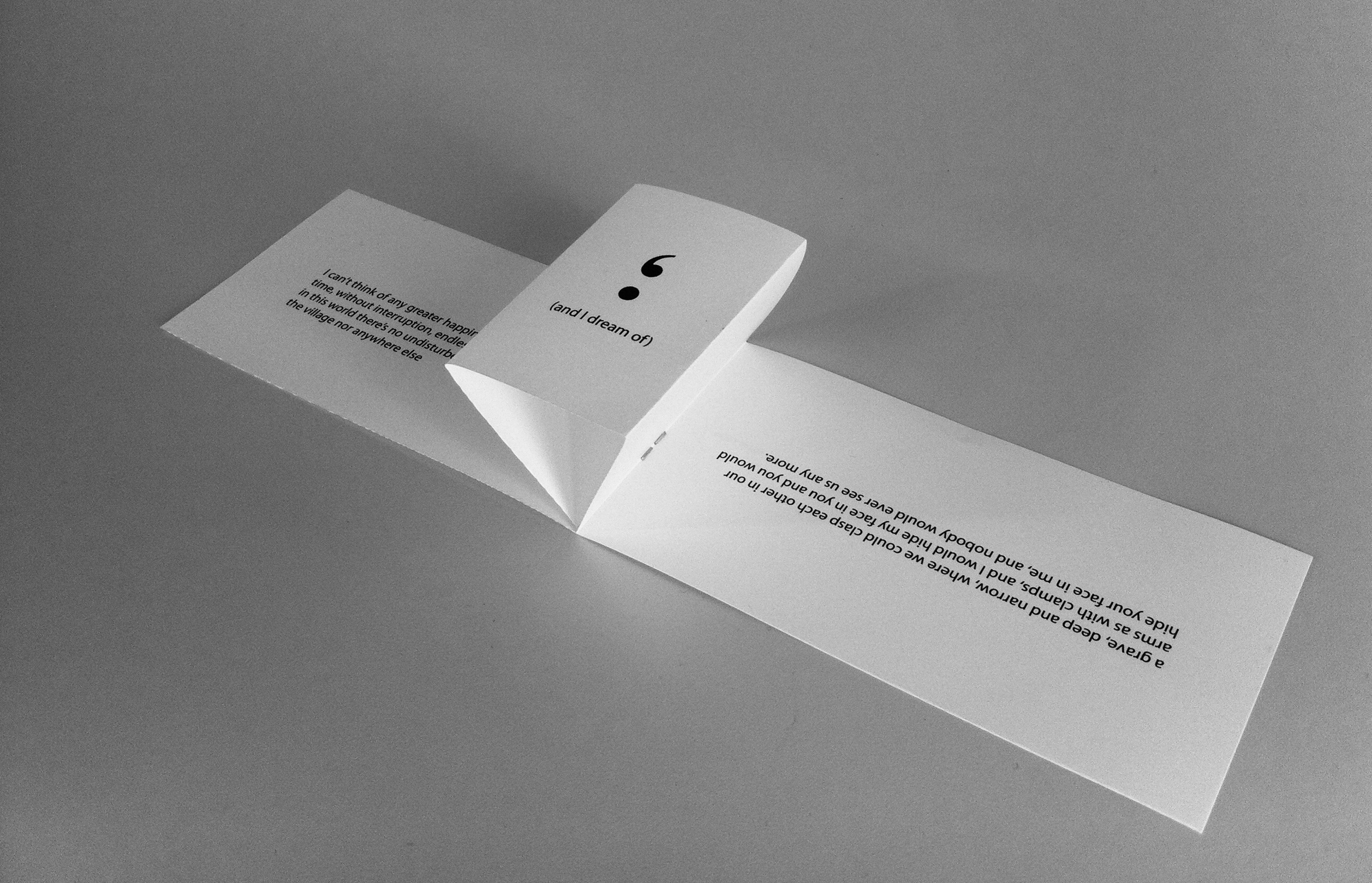

“I can’t think of any greater happiness than to be with you all the time, without interruption, endlessly, even though I feel that here in this world there’s no undisturbed place for our love, neither in the village nor anywhere else.”

I sway back;

“;”

I pause.

I sway forth,

“and I dream of a grave, deep and narrow, where we could clasp each other in our arms as with iron bars, and I would hide my face in you and you would hide your face in me, and nobody would ever see us any more.”[23]

I can stand up, go down the stairs and walk the streets without you, surrendering to the city that swallowed you. Or I can sway forth and drop into the emptiness of a vast grave. There, I might find you. But I still sit where I am sitting; in the semicolon, between the impossibility of embracing you in the place where life remains, and the possibility of embracing you where life is absent. How far can I push back these two parts of the whole? How long can I stay on the edge of the building, watching it disappear into a city of thousands of similar buildings? I gaze at the semicolon; the words on the page are blurring; the street below lies empty; the book is falling apart; my pause lingers…

03. The semicolon as the space of pause, of imagination. From the project The Impossible Book.

Published 24th September, 2015.

Notes

[01] Harvey, David. 2008. ‘The Right to the city’ in New Left Review, Vol.53, p. 23.

[02] Genc, Kaya. 2013. ‘The standing man of Taksim Square: a latterday Bartleby’ in The Guardian, Thursday 20th June, 2013 (accessed 25th June, 2013). In Herman Melville’s Bartleby the Scrivener, Bartleby refuses to work and simply restates the phrase ‘I would prefer not to’. As Genc notes in his blog post, it would not have been surprising if the security officers searching the Standing Man’s backpack uncovered a copy of Bartleby, the Scrivener.

[03] The Ataturk Cultural Centre represents the history of secularisation of Turkey by Ataturk.

[04] Deleuze, Gilles. 1995. ‘Three Questions on Six Times Two” in Negotiations, 1972-1990. Trans. Martin Joughin. New York: Columbia University Press, p.35.

[05] Elden, Stuart. 2004. Understanding Henri Lefebvre. New York: Continuum, p.118.

[06] Lefebvre, Henri. 2002. Critique of everyday life, Vol. II, trans. J. Moore. London: Verso Books, p. 347.

[07] Elden, Stuart. 2004. Understanding Henri Lefebvre, p.118.

[08] Lefebvre, Henri. 2002. Critique of everyday life, Vol. II, p.347.

[09] Lefebvre, Henri. 2002. Critique of everyday life, Vol. II, p.351.

[10] This paragraph is a rewriting of a part of the short story ‘Mon and Gnac’ in Italo Calvino’s Marcovaldo collection. Calvino, Italo. 2001. Marcovaldo. trans. W. Weaver. London: Vintage Books, p.71.

[11] DeLillo, Don. 1992. Mao I’. London: Vintage, p.34.

[12] Springer, Simon. 2011. ‘Public Space as Emancipation: Meditations on Anarchism: Radical Democracy, Neoliberalism and Violence’ in Antipode, Vol.43 No.2, p. 542.

[13] In Lefebvre’s terms, public space that is controlled by government or other institutions, or whose use is regulated, is referred to as “representation of space”, whereas public space as it is actually used by social groups is called “representational space”. See also: Springer, Simon. 2011, ‘Public Space as Emancipation’, pp.537-8.

[14] Springer, Simon. 2011. ‘Public Space as Emancipation’, p. 537.

[15] Springer, Simon. 2011. ‘Public Space as Emancipation’, p. 537.

[16] Springer, Simon. 2011. ‘Public Space as Emancipation’, p. 538.

[17] Simone, AbdouMaliq. ‘Infrastructure: Introductory Commentary by AbdouMaliq Simone’. Curated collections, Cultural Anthropology Online, November 26, 2012. Available here (accessed 22.09.2013)

[18] Tschumi, Bernard. 2001. Architecture and Disjunction. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, p 123.

[19] Lazzarato, Maurizio. 2011. ‘The dynamics of the political event: process of subjectivation and micropolitics’, European institute for progressive cultural policies (accessed 6th May, 2014).

[20] Mirdamadi, Mohsen. Interview with Sepideh Karami. Personal interview. Tehran, August 25, 2012.

[21] In Architecture and Disjunction Bernard Tschumi explains ‘expanded sequences’ in contrast to ‘contracted sequences’, which he defines as follows: “we might see the beginning of a use in space followed immediately by the beginning of another in a further space. Contracted sequences have occasionally reduced architecture’s three dimensions into one.” Tschumi, Bernard. 2001. Architecture and Disjunction, p.166.

[22] Tschumi, Bernard. 2001. Architecture and Disjunction, p.166.

[23] Kafka, Franz. 2008. The Complete Novels of Kafka. London: Vintage, p.547.

Figures

Banner.

The 'Standing Man' protestors following choreographer Erdem Gunduz during the Gezi Movement, Istanbul, 2013. Still from YouTube video.

01.

Standing man, Occupy Gezi Movement, Istanbul, 2013. Still from YouTube video.

02.

Unfinished building, Liberty Street, Tehran during the 1979 Revolution. Still from A Dialogue with Revolution, 2013 [Film], directed by Robert Safarian.

Unfinished building, Liberty Street, Tehran during the 1979 Revolution. Still from A Dialogue with Revolution, 2013 [Film], directed by Robert Safarian.

03.

Image from the project The Impossible Book, Sepideh Karami, 2013.

Image from the project The Impossible Book, Sepideh Karami, 2013.

https://doi.org/10.2218/dy3z6m57