Five Lessons in a Ficto-Critical approach to design Practice research

Hélène Frichot

In the following text I propose to outline five preliminary lessons in a ficto-critical approach to creative research practices in architecture, or more precisely, between architecture and philosophy; a transversal relay I pursue through my own research. I will identify these creative and critical practices as operating amidst what can be called an ‘ecology of practices’, a formulation I appropriate from the philosopher of science Isabelle Stengers (who also stresses the power of fiction with respect to explorative practices in the sciences) although I will ask whether it might be helpful to refer instead to ecologies, placing the stress on the plural, in order to allow for more diverse transdisciplinary encounters. I propose ecologies of practices as surely every ecology jostles alongside another ecology; as one ecology brims over the threshold into another it either wreaks havoc and brings about the decline of a neighbouring less resilient ecology, or else enjoins a more powerful composition, an allegiance. At these thresholds an ethics is called for, and the possibility of experiencing-experimenting with an ethico-aesthetics.[01] With respect to much of what I will discuss here I am indebted to the researchers I have had the opportunity to work with in the School of Architecture and Design, RMIT University and within ResArc, the research institute that conjoins the four schools of architecture in Sweden. In many instances I have guided these researchers through their PhD projects, as they, in turn, have guided me into an understanding of the very difficult domain of research by or through design. In particular I thank Michael Spooner, Julieanna Preston, and Margit Brünner for kindly allowing me permission to reproduce their images.

For those of us brought up in the learning environment of the architectural design studio there is something second-nature about thinking through or by the design act, and these prepositions, as Christopher Frayling, Peter Downton and Jane Rendell have all pointed out are, of course, crucial.[02] I will refer to such labour below as a process of thinking-doing suggesting an intimate relay between design thinking and acting. There are also great risks, and troubling models that have emerged when it comes to the development of the PhD through project work, models that suggest ready-made templates can be applied to research by design, or that a PhD can be completed swiftly and pre-emptively, simply as in the course of what you are doing, in that it might be assumed that you have already ‘mastered’ your craft, and are now capable of reflecting on it by relating it to your ‘natural history’ by recourse to a non-critical, weak phenomenology that underestimates the political power of affect, and the ecology of practices you thereby alter. While these models are troubling, and while it is certainly vital that we address these models, here I want to circumvent this debate. Instead I prefer to venture the more affirmative and generous project of acknowledging diverse ecologies of practices.

Stenger’s ecology of practices can be summarised in the following way: it includes a respect for the differences between practices and that no practice should be defined as just like any other; seeing practice as a non-neutral tool for thinking through what is happening, a tool that can be passed from hand to hand thereby transforming both the situation and the one who handles the tool; framing what is happening in a minor key and in direct response to our local habitat or from the midst of those issues which confront us; and finally, never believing we have arrived at an answer once and for all, but maintaining nevertheless an affirmative and not a negative, nor even a deconstructive demeanour. Although Stengers’s work is addressed to the sciences, and discussed in the greatest detail across the seven parts of the two volumes of Cosmopolitics (2010 and 2011) in which she builds on seven problematic landscapes in the sciences, the question of practice and its relation to thinking is one that is shared with architecture.[03] Practice, including research strategies, teaching-learning, and the development of research in the professional sphere, focuses on local and particular problems, which immanently define a practice’s relations amidst its environment-world or milieu, whether that be the laboratory, the drawing office (or CAD lab), or the building site.

To return to my five lessons, which I will situate and unfold amidst ecologies of practices, I want to address the question of method, quite simply how it is we do what we do, and in turn methodology, that is, how, once we have undertaken some research action, we might reflect and thereby describe the logic of our approach or method.[04] This, I should point out, is not a question of meaning but one of use and application. I want to address the question of methodology, even of anti-methodology – as an approach – because I see that this is one of the key issues that architecture researchers face when they identify themselves neither as historians, nor squarely as theorists, but perhaps something more akin to creative practitioners keen to conjoin their doing with their thinking, exploring productive relays between theory and practice. Much as Paul Feyerabend argues in Against Method, it is not a methodology of proscriptive or “naive and simple-minded rules” that I deem useful, rather an open-ended anti-method, however paradoxical this might sound.[05] Epistemology, animated and extended through the thinking-doing of architecture, can be approached not in a strict way, but in an opportunistic and situated way, an approach we are implicitly familiar with from the learning environment of the design studio; an approach that allows the bringing together while remaining sufficiently distinct of thinking and doing via disjunctive syntheses. As Feyerabend points out, the risks of an overweening method means a suppression of one’s sense of humour; an inflexibility with regard to the rules; an inability to draw on intuition; a dried up imagination; and the use of language that is no longer one’s own but composed of platitudes and standard academic tropes.[06]

The five lessons will include: 1. A ficto-critical opening as a means of setting out an approach and what is to follow; 2. Lesson two will commence with Michael Spooner’s Clinic for the Exhausted, in order to discuss the importance of reinventing precursors, and even murdering precedents, because we always-already proceed from amidst an ecology of practices of some kind; 3. Lesson three will open by way of an introduction to Julieanna Preston’s performative project Room, Wool, Me, You (2012) suggesting an instance of an ecology of practices and ‘your situated knowledge’, or how the thinker-doer of design specifically locates her work and best follows the materials of an occasion. 4. Lesson four will open with the posthuman landscapes of joyful affect Margit Brünner composes. Here I will explore ethical experimentation as the reversibility of experiencing-experimenting. Then I will close with a fifth lesson, 5. Making worlds consistent on a plane of nature-thought.

Lesson 01: A Ficto-Critical Opening

Between 2011 and 2012, as I was charting a line of flight from Melbourne, Australia to Stockholm, Sweden, I was involved in organising a collaborative essay that was published in the TU Delft architectural journal, Footprint, in an issue dedicated to Architecture Culture and the Question of Knowledge: Doctoral Research Today. There I attempted to curate, after the fact, the work of a collective of PhD researchers, some recently completed and some still in the midst of undertaking their research by or through design, all of whom were working within a research stream I had convened in the School of Architecture and Design, RMIT University, called Architecture+Philosophy. Via a form of curatorial conceit I gathered their diverse projects under the methodological and ethological rubric of ‘ficto-criticism’. The title of our collaborative work was An Antipodean Imaginary for Architecture+Philosophy: Ficto-Critical Approaches to Design Practice Research. Ficto-criticism, and an emphasis on the powers of fiction, enabled a means of bringing creative, experimental design work together with affirmative modes of creative criticality.In this text I stressed that the collected Architecture+Philosophy researchers placed an emphasis on critical and creative invention and a structured indeterminacy that manifests in the wild association of images and ideas toward the procurement of innovative as well as politically engaged minoritarian architectures. I argued further that fiction is the powerful means by which we can speculatively propel ourselves into a future, and that criticism, or criticality, to emphasize the embeddedness of researchers in their milieu, offers the situated capacity to ethically cope with what confronts us. I wanted to claim that the critic or theorist is in the midst of the work, is contaminated by the work, contributes to the work, and even creates the work, for the critic is also the creative practitioner. As Brian Massumi argues “critique is not an opinion or a judgment but a dynamic “evaluation” that is lived out in situation,” which is to say, critique or criticality as a demeanour should not be about imposing preconceived attitudes, opinions or judgments, but needs to respond immanently to the problem at hand.[07] That the practitioner is also, in turn, the critic of her own work allows criticism its creative turn and purposively puts it to work immanently in the creative act. In direct reference to ficto-critical approaches, the Australian theorist Anna Gibbs writes that “the researcher is implicated in what is investigated,”[08] or else, sometimes quite abruptly, there even occurs the event of the “collapse of the ‘detached’ and all knowing subject into the text.”[09]

My own interest in this approach comes from the idea that ficto-criticism takes a literary approach to philosophy, acknowledging philosophical precursors who have taken recourse to modes of fiction as a means of thinking and constructing new environment-worlds and new processes of subjectification, new ways of becoming amidst immanent milieux: Hélène Cixous and Luce Irigaray’s écriture feminine, Roland Barthes’s pleasures of the text and his lovers discourse, but also Michel Foucault who claims that all his work can be read as a fiction, and Deleuze and Guattari who have a knack of telling stories as they creatively construct their concepts and lay out their planes of conceptual consistency. Stephen Muecke, citing Jacques Derrida, suggests that ficto-criticism is the name that can be given to those critical forms that deform literature from within. Similarly, for architecture, I’d like to argue that we are in great need of critical-creative forms that can deform architecture from within, that can disrupt its comfortable habits, insidious opinions, and resilient clichés. Gibbs also argues that “the heterogeneity of fictocritical forms bears witness to the existence of fictocriticism as a necessarily performative mode, an always singular and entirely tactical response to a particular set of problems - a very precise and local intervention,”[10] which also aligns the ficto-critical approach with Stenger’s ecology of practices as necessarily localised in terms of application.[11]

If there were time, we could probably sketch out what Michael Spooner calls a ‘discontinuous genealogy’ that also includes the famous novels of the existentialists, Beauvoir, Sartre, Camus, and even earlier, the essays of Montaigne. And yet this list of precursors does not necessarily get us closer to the difficult domain of architecture, and the ‘practice turn’ or the global spread (following the Bologna accord) of this new model of research training. To bring us to the question of increasingly established yet still emerging design research practices in architecture, I will defer offering an outline of this discontinuous genealogy, which so far forgets to name such important feminist intercessors as Jane Rendell, Katja Grillner, Jennifer Bloomer, Diana Agrest, Doina Petrescu, and forgets also its many forefathers. I want to place an emphasis instead on an approach, and in any case, as I will argue, every architectural thinker-doer needs to reinvent their own genealogy of precursors. I will expand on the ficto-critical approach by following Stengers where she presents her cosmopolitical project; what she also calls her ‘ecology of practices’, where she too discusses the powers of fiction, which leads me to lesson two.

01. RMIT University Building 8 Becoming Boat. Clinic for the Exhausted. Michael Spooner, 2007-2011.

Lesson 02: Reinventing your precursors, and even murdering your precedents

Michael Spooner exhibits the symptoms of an obsessive character, he indefatigably riffles through the paper pages of the library, and surfs the many electronic archives now available on line. He arranges choice samples in his chambre de fleurs.[12] The obsessive is an aesthetic figure that Mark Dorrian and Adrian Hawker take care to distinguish from the myth of the creative genius that still plagues architecture.[13]Spooner the obsessive architect is transported by his projects, and is less authoring than authored by them. He himself makes much use of yet another aesthetic figure, and that is the Troubadour, who does not ‘own’ the stories he tells but instead carries them from one village or town to the next, transforming them with each telling.[14] The specific, enduring obsession Spooner developed as an architecture undergraduate, and which he pursued throughout his PhD project, which I was so fortunate to supervise and which is now published in the new AADR (Art Architecture Design Research) series of Spurbuch Verlag, is with the distinctive civic character of RMIT University Building 8 completed by Edmond and Corrigan in 1993, where the RMIT University architecture program is housed on the top floor.By way of a drunken vision communicated by epistolary means from one architect, Howard Raggatt, to another, Peter Corrigan, Building 8 is let loose from its moorings on Swanston Street Melbourne, and sets sail into an architectural imaginary as ocean liner. This collapse of imagery of building and boat then rewards Spooner with the license to institute his Clinic for the Exhausted, where the exhaustion in question is carried out by the furious, seething, superimposition of an overabundance of images drawn from diverse sources, creating the wonder of an anachronistic chaos that settles briefly in two clinics, The Swimming Pool Library and The Landscape Room, but crucially the clinic is also composed as a textual contribution.

As Spooner describes it, his approach is to take as many images as possible drawn from literature, film, architecture, art, and cram them into a lead pipe until they explode, manufacturing what he calls a ‘discontinuous genealogy’.[15] As such he offers an implicit critique of the architectural designer’s habitual and often uncritical use of design precedents. It is a serendipitous fact that spoonerism is that literary technique, or rather slip of the tongue, that muddles the forward letters of two words, a technique that much resembles the various word plays of Raymond Roussel, once called the Marcel Proust of dreams. Two almost identical sentences were used to compose the beginning and end of Roussel’s novel Impressions d’Afrique (1910). The creative process of writing the novel was generated between a choreographed yet minor textual slip, resulting in a major shift in meaning between the two sentences ‘the white letters on the cushions of the old billiard table (les lettres du blanc sur les bandes du vieux billard) and ‘the white man’s letters on the hordes of the old plunderer’ (les lettres du blanc sur les bandes du vieux pillard). The minor displacement of one letter encountered in the first sentence, that is, billard [billiard] transforms it into the word pillard [plunderer] to be discovered in the latter sentence. As Foucault explains, “the infinitesimal but immense distance between these two phrases will give rise to some of Roussel’s favourite themes” from which a fictional landscape unfurls.[16] Suffice to say, Roussel counts among Spooner’s most precious precursors, and he has dedicated one chapter, ‘Rousell’s Epigenetic Landscape’, to this forebear.

The lesson here: despite appearances, Spooner’s Clinic for the Exhausted is not mere postmodern pastiche, but out and out anachronistic, historical collapse, the concrete presence of the past in the present, exactly because the past still presently affects us. Spooner reinvents his precursors, and even does away with or symbolically murders his precedents (an Oedipal relation, perhaps). It so happens, from time to time, that a creative force emerges that enables the subsequent recognition of a formidable genealogy of precursors that would have otherwise remained disconnected, non-visible, even unrecognisable. This argument was forwarded by Jorge Luis Borges in his essay ‘Kafka and his Precursors’ (1970), whereby he suggests that it is exactly through the lens of Kafka’s work that a genealogy can be retrospectively configured, that is to say, a distinct literary, or let us say ‘architectural’ quality is perceived, that would not have otherwise emerged. Or else it is how, recognising the burden of influence, we nevertheless “restore an incommunicable novelty to our predecessors.”[17] So it is with Spooner who demands that we ask: who are my conceptual friends and enemies, and how do I choreograph their past performances amidst the compositions I propose? What composition do I already form part of? Stengers has another way of framing this with respect to an ecology of practices: it is not that we can refer to a ‘we’, ‘we architects’, ‘we creative practitioners’ in advance of our practice, instead, it is through the practice that this we will emerge (for the meantime), as we discover our friends and foes.

Lesson 03: An Ecology of Practices and your situated knowledge

A woman with her thicket of white-grey hair, her head bent over in concentration and the paradox of a calm expression worrying her face. An enclosed room, viewed only through a restricted portal, and then remotely mediated by way of a screen located just outside the room. A bale of greasy wool, a blanket, a candle, some water, some gingernut biscuits for sustenance. You and me. And over three long days the woman redistributes the wool: as interior carpet landscape, or else she packs it tight blocking the opening of a side door, or else she flings it toward the ceiling. A bale of greasy wool is as good as a coyote, she says to herself. I love the greasy wool and the wool loves me, and between the two a relation is formed that transforms each party. I love to you, she murmurs, an Irigarayan call: “I love to you means I maintain a relation of indirection to you. I do not subjugate you or consume you.”[18] All the while, the blind eye of a camera captures her erratic, slow, un-choreographed movements. Julieanna Preston is a New Zealand academic and creative practitioner of architecture and interiors, who asks persistently, what can an interior surface do? She uses an exacting, exhaustive material approach to speculate on political events, real and imagined, using fictional writing and imagery, as well as sculpted objects or props, installation and performance. Her work has developed toward a series of site-specific installations where she deploys her performing body as one medium amidst many, using wool, also mud, she is ever immersed. She has frequently placed an emphasis upon the materials of her local institutional environments so as to allow them to speak. Her engagement with the vibrant material of her local problematic field is a question of creative resistance. I will explain.In his book dedicated to Michel Foucault, master analyst of the dynamics of power relations in the spatio-temporal domain of institutions, Gilles Deleuze makes the seemingly paradoxical claim that resistance comes first.[19] Resistance is not only a political gesture that responds to oppressive forces, but political in its generative power. Elizabeth Grosz contributes to this argument by making a distinction between ‘freedom from’ and freedom to’, where the former denotes resistance in response to some perceived, pre-existing oppressive power, patriarchal or otherwise, the latter pursues material expression through a freedom to act and thereby (re)make oneself and the present otherwise.[20]

Resistance, as Julieanna demonstrates, can also quite simply be related to material resilience, how a certain material is resistant to moisture, another to sound, and how resistance at times may also have something to do with yielding. Preston reclaims the priority of resistance as a creative act. While at first seeming to respond to a pre-given oppressive force, through her creative works (inclusive of writing-architecture) she turns resistance around so that it is no longer a question of freedom from, but a freedom to act amidst an environment-world using creative material means.

To discover what lesson we learn here, we need to slow down, and begin with the term ‘ecology’ as it is employed in Stenger’s ‘ecology of practices’. Ecology, as Gregory Bateson reminds us, determines that the basic unit of survival is between organism and environment: here is our utter material, relational immersion. As Jane Bennett explains: “ecology can be defined as the study or story (logos) of the place where we live (oikos), or better, the place that we live.”[21] That living suggests all manner of practices. An ecology is a sticky web of connections, which Stengers, as Haraway, also takes on in terms of a web of practices.[22] Ecology reminds us that there is no such thing as an isolated action or practice, there is no outside that which constitutes collective enunciation. Our concerns gather much like confederacies, as Bruno Latour puts it, and furthermore, as I have already indicated, ecologies are not necessarily harmonious, but also rife with controversies. Our milieu directly presents us with situations or ‘occasions’ in which we have the opportunity to act, and strengthen our compositions, or else retreat. How do we make the best of what happens to us?

Neither entirely ‘constructed’ nor entirely given, the erstwhile privileged point of view habitually ascribed to the self-same phenomenological subject is rather constructed by the world, or else emerges amidst an environment-world or milieu. An emphasis can be placed here on the priority of events and material relations, something happens, and slowly, in fits and starts the subject emerges as a process of subjectification amidst their seething material environs. The challenge becomes how we can develop an ecological sensibility that attends to the horizontal relations between humans and things. In When Species Meet Donna Haraway celebrates this immersion in the following way: “I love the fact that human genomes can be found in only about 10 percent of all the cells that occupy the mundane space I call my body; the other 90 percent are filled with the genomes of bacteria, fungi, protists, and such…”[23] On writing her book Vibrant Matter, Bennett similarly proclaims: “the sentences in this book also emerged from the confederate agency of many striving macro and micro-actants: from “my memories,” intentions, contentions, intestinal bacteria, eyeglasses, and blood sugar, as well as from the plastic keyboard, the bird song from the open window, or the air of particles in the room, to name a few of the participants.”[24] Here the point is, that what Haraway has famously called ‘situated knowledge’ is not subject-centred nor an opportunity to relate pre-packaged stories of one’s memories, one’s life, one’s travels, one’s dreams, one’s fantasies but instead our points of view, situated for the time being only, construct us and continue to do so as the oculus of the point of view contracts and expands as a result of so many micro and macro-encounters.[25] It is “The great principle” as Deleuze poignantly points out that “Things do not have to wait for me to have their significations.”[26]

Deleuze also elaborates this question (of position, situation, situated knowledge) succinctly in The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque. Yes, it is a question of point of view, but point of view composed as “not exactly a point but a place, a position, a site” but not assuming a dependence with respect to “a pregiven or defined subject; to the contrary, a subject will be what comes to the point of view, or rather what remains in the point of view.”[27] Environment-world and subject come to be reciprocally produced around multiplicitous points of view, ever in motion.

In a similar vein, but stressing again how we might turn these observations into practice, Stengers asserts that tools (both conceptual and material) for thinking are not about a thinker or subject a priori, but rather about a situation, a relation of relevance between a situation and a tool. Our thinking-doing is not about recognition based on the already known, but a decision to make what was virtual actual, compelling us to actively think and not merely to passively recognise. As such ecologies of practices are less about describing what is in our own local ecology, than making something new possible, as well as a construction of what Stengers calls “new ‘practical identities’ for practices,” including the potential of what a practice may become.[28] Feminist practices, and what Haraway calls ‘collective discourses’ as exemplified in Preston’s work, do not constitute a mere special interest group, but contribute to an “earthwide network of connections, including the ability partially to translate knowledges among very different – and power-differentiated- communities,” it is a question of deploying a feminist objectivity as partial vision, limited location, situated knowledge and embodied learning.[29] The lesson we learn here is: a practice is never independent of its environment or milieu, and we do not know in advance what a practice can become, it is a matter of experiencing-experimenting.[30]

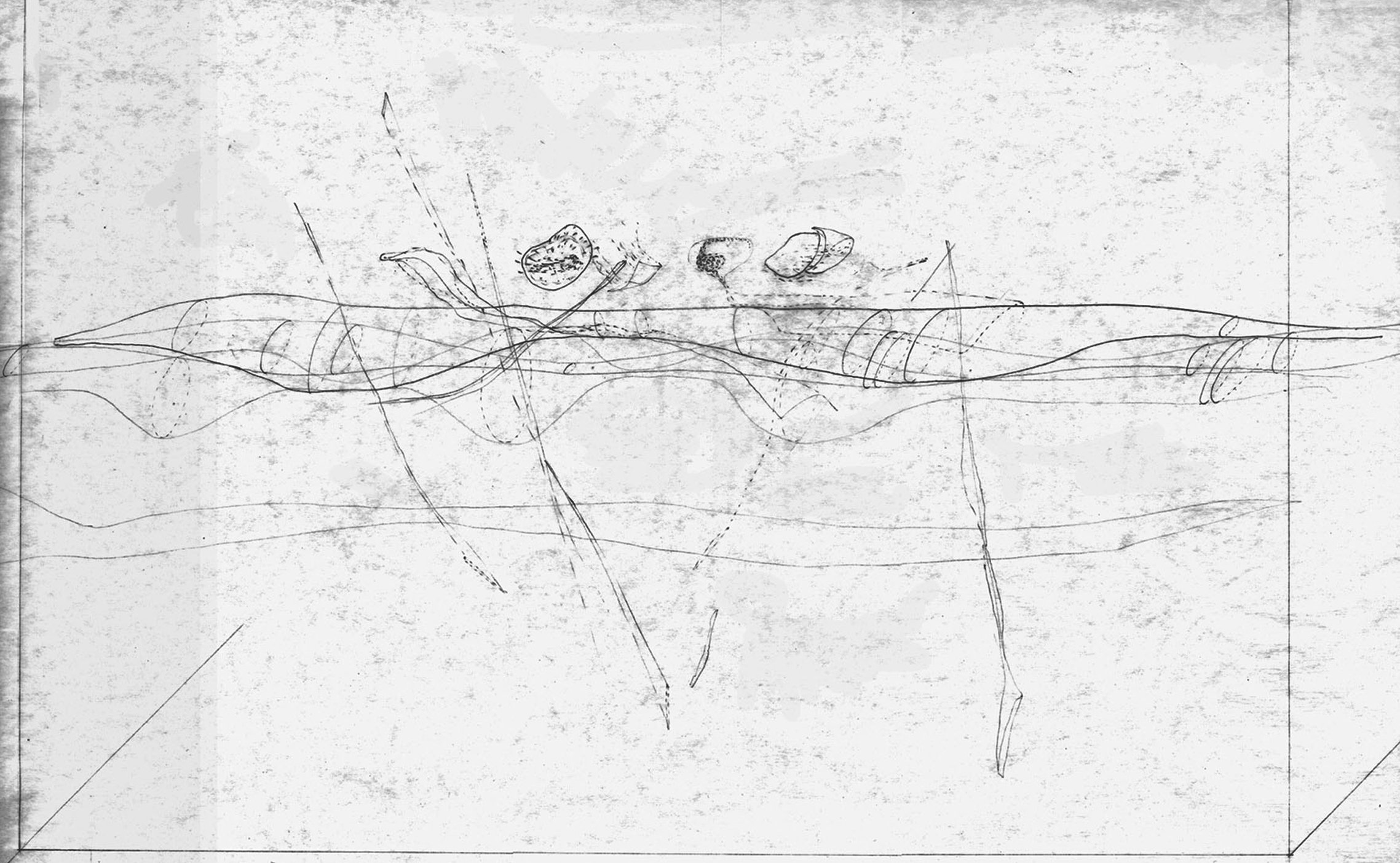

02. Schwebebild - Cosmethic Space Refinements. Margot Brünner, 2002.

Lesson 04: ethical experimentation, and the reversibility of experiencing-experimenting

When I first encountered Margit Brünner she was falling out of a hammock while attempting to sketch a cluster of vibratory lines through the communicating pistil of a long prosthetic drawing device. She lost balance briefly, and tumbled to the floor with laughter. This was at an Expanded Writing Practices symposium at the University of South Australia in September 2009. If you are as fortunate as Margit then your ethical experimentation will achieve encounters that produce joyful affects. Margit’s work is ostensibly located between the spatial arts and performance art, but she is an architect. Her explorations endeavour to discover the best means of producing joyful affects, with an emphasis on the milieu, or relationship between the environment-world and ever-transforming subject (or processes of subjectification): this is what she names atmosphere. Hers is a practice of immanence, ever located, situated, inspired by embodied learning.Nearly ten years earlier, during her first visit to Australia, Margit undertook a series of ‘cosmethic space refinements’, which explored methods for surveying and describing the atmospheres of a selection of public spaces in Melbourne.[31] The invented tools she tested for her survey included: catcher, surveyor, implement, and pollination. She explains her process:

My body is the surveying instrument. Its sensitive ability is extended with a technical object, which anchors the body within time and space. Each method is focused on a specific aspect and is realised on particular conditions. All methods share the elementary principle of ‘expanding reality’, projecting a thought into space. Every arrangement communicates with the atmosphere, ever sifting, catching, memorising, absorbing, assimilating, transcribing, and translating. It is an active delayer, enlarger, intensifier, distiller, separator, catcher, stimulant and transporter of the emerging, fleeting, and growing phenomena. The arrangement provides an opportunity for space to reveal its immanent moods and tempers.[32]

Margit’s work engages both urban and wilderness (specifically a property at Oratunga South Australia) milieux, but she respects no ‘great divide’ between nature and culture. Her engagements with posthuman landscapes do not make distinctions between the natural and the cultural but stress instead an approach driven by the urgent question: how do I dialogue with my environment-world as affective atmosphere? She admits that joy resists being utilised for representative purposes.[33] This can result in a failure of representational means, a limitation of our capacity to capture, through video, drawing, photography the profound encounter that has taken place.

With respect to ethical experimentation amidst an ecology of practices, it is crucial to point out a distinction between morality, or moral rules over-determining our relations in a world through pre-given codes (much like the over-determined application of methodology noted in the opening to this essay), and ethics as a practice worked out between transforming embodied processes of subjectification and a local situated environment-world (umwelt) or milieu. Ethical experimentation (and the French language: expérience) draws the terms experience and experiment together, and as Deleuze explains in his reading of Spinoza in Spinoza: Practical Philosophy (1988), ethical experimentation also suggests a way of following the materials of a situation, as a craftsperson follows the grain of the wood. Margit follows the materials of her encounters, thereby honing her ‘atmospheric skills’. As she explains in her thesis glossary atmospheric practice is a ‘method of becoming joy’. She follows the Spinozist formula of the passage of affect: where sad passions reduce a mode’s capacities of expression, joyful affects empower a capacity to act in a world, and thereby to make an affirmative difference: “Ethology, whenever human practices are involved” as Stengers explains “is based on productive, on performative experimentation with regard to modes of existence, ways of affecting and being affected, requiring and being obligated…”[34] In fact Margit dispels entirely with the distinction between art and everyday practices (we might name Nietzsche a precursor here) and suggests that practice is about daily navigation toward making the best of all encounters, it’s a tireless field-testing. Her cosmology is brought together with her ethics…toward a joyful cosmethics; and ethology (given that the emphasis is on behaviour rather than reasoning per se) is less argued for than performed.[35]

And with such cosmethic experiments, which draw us now toward a cosmopolitical conclusion, I may well have ventured too far beyond the heavily policed boundaries of what pertains strictly to architectural project work. But in introducing these (posthuman) landscapes becoming with expressions of joy unfurled in the midst of encounters and via striving processes of subjectification, I at least hope to rejuvenate architectural thinking-doing as a ‘critical projective’ project (a formulation constructed by Helen Runting and Fredrk Torrisson in the Approaches, Tendencies, Philosophies and Communications ResArc Sweden PhD courses). Who is the experimenter, what does she do? “The experimenter is a creator. She brings into existence a being that will serve as a reliable witness to what determines that being’s behaviour.”[36] In closing lesson four I want to assert three things: 1. Processes of learning always assume some milieu; 2. It follows that our knowledge producing practices emerge as a result of worldly encounters; 3. And the concepts we deploy as so many tools to respond to such encounters continue to contribute to how we situate ourselves.

Lesson 05: Making Worlds Consistent on a Plane of Nature-Thought

Making worlds consistent on a plane of nature-thought, or else across what can also be called a ‘plane of immanence’, may require all the powers of fiction and ficto-criticality we can muster, and all manner of strange tools and concepts so that we can make the best of our material encounters and relations.[37] The plane of nature-thought, yet another concept in the heterogeneous and perilously slippery lexicon or ‘heteroglossia’ of Deleuze and Guattari, suggests in the first place a collapse or else a reversal of the distinction between sensible and intelligible realms (as bestowed on us by Platonism), and in the second place reminds us that we always, necessarily, act from the midst of things, from the middle, the milieu, from our local environment-worlds, where we strive to address immediate problems.[38] The plane is quite simply the milieu of our present-time stratum, but the plane also suggests a plan. That is to say, we can to a limited extent curate or choreograph our acts from amidst this milieu. Heteroglossia, a term that Haraway uses in her influential essay ‘Situated Knowledges’ suggests that part of this method pertains to the language we use, stressing explorative expressions of difference issuing from our diverse conceptual tongues, including the neologisms we must necessarily invent to make an account of our emerging worlds. And slowly, by increments, and hopefully, we can undertake an ethical coping amidst our vicissitudes, and even develop some expertise in this ‘ethical coping’ as a form of ethical know-how, as Francesco Varela puts it.[39]The plane of nature-thought is also a conceptual prompt to remind us that ecology is not just a niche or special interest domain for nature-lovers, it pertains, as Guattari compellingly argues, to the complex inter-relations between mental, social and environmental registers, which we only think separately or apart at our own ethological and ecological peril.[40] How do I deal with the vertiginous realisation that it is less my point of view on a world as controlling or authorial gaze, than the world that constructs my point of view as we enter into an embrace, or reciprocal capture? As Nigel Thrift argues in ‘Steps to an Ecology of Place,’ we cannot extract a representation of the world because we are slap bang in the middle of it co-constructing it with human and non human others for numerous ends (or, more accurately, beginnings).”[41] And as Latour and also Haraway argue, we must get around our habit of thinking a ‘Great Divide’ between Nature and Culture (or Nature and Thought), but this is not to suggest that we don’t extend the repertoire of our practical experiments and diverse, explorative means of communicating them.[42]

The ficto-critical approach offered in this context is intended to suggest an open and generous mode of situating expression, of allowing voices to be heard, voices that can respond to the great urgency of discovering new ways, new methods for our discipline. Methodology is that question of how, how do we go about doing this thing we do, this thinking-doing? Beyond the habits and clichés and mere opinions, but while acknowledging a disciplinary context where requirements and obligations do exist: it’s not a free for all. And an approach is less to do with sufficient reason, and the best of all possible worlds, than with sufficient consistency for the time being, as an immediate, immanent act of composition, given available material flows and encounters. Haraway has another word for this: she calls it ‘worlding’, which suggests all manner of posthuman landscapes, and cross-species relations.[43] What is it that architecture does if not attempt, even if fleetingly, to achieve a minimal durability, and a certain consistency amidst its precarious milieux?

When we situate design research amidst an ecology of practices we open the way toward enabling a respect – even amidst our many controversies and disagreements – for differences between practices, between the practices of architectural historians, theorists, practitioners, pedagogues, and for those – sufficiently daring or foolhardy – determined to cut transversal lines across these distinctions too. What is required, whatever our research undertaking, is certainly a critical vigilance, or rather a demeanour of criticality, with respect to our habits and concerns as we keep an eye on our disciplinary requirements and obligations, whether they have begun to overly constrain us, or whether they still enable wild, even if sometimes uncoordinated leaps of research thinking-doing.

Published 24th September, 2015.

Notes

[01] Guattari, Félix. 1995. Chaosmosis: An Ethico-Aesthetic Paradigm, trans. Paul Bains and Julian Pefanis. Sydney: Power Publications.

[02] Frayling, Christopher. 1993. ‘Research in Art and Design’ in Royal College of Art Research Papers, Vol. 1 No. 1, p.5; Downton, Peter. 2003. Design Research. Melbourne: RMIT University Press, p.103; and Rendell, Jane. 2010. Site-Writing: The Architecture of Art Criticism. London: I.B. Tauris, pp.1-20.

[03] Stengers, Isabelle. 2010. Cosmopolitics I, trans. Robert Bononno, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press; Stengers, Isabelle. 2011. Cosmopolitics II, trans. Robert Bononno, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

[04] See Harding, Sandra. 1987. ’Introduction: Is There a Feminist Methodology?, in Harding, Sandra, ed. Feminism and Methodology. Bloomington IN: Indiana University Press.

[05] Feyerabend, Paul. 1993. Against Method. London: Verso, p.9.

[06] Feyerabend, Paul. 1993. Against Method, pp.11-12.

[07] Massumi, Brian. 2010. ‘On Critique’ in Inflexions 4: Transversal Fields of Experience (December), pp. 337-338. Available here (Accessed 13th February 2013).

[08] Gibbs, Anna. 2005. ‘Fictocriticism, Affect, Mimesis: Engendering Differences’, in TEXT, Vol. 9. No.1 (April). Available here (Accessed 6th April 2013).

[09] Muecke, Stephen. 2002. ‘The Fall: Ficto-Critical Writing, in Parallax, Vol.8 No.4, p.108.

[10] Gibbs, Anna. 2005. ‘Fictocriticism, Affect, Mimesis: Engendering Differences’.

[11] See Stengers, Isabelle. 2005. ‘The Cosmopolitical Proposal’ in Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel (eds.), Making Things Public: Atmospheres of Democracy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, pp.; 2005. ‘Introductory Notes on an Ecology of Practices,’ in Cultural Studies Review, Vol. 11 No. 1 (March), pp.183-196; 2010. Cosmopolitics I; and Cosmopolitics II.

[12] http://chambredefleurs.tumblr.com

[13] Dorrian, Mark and Hawker, Adrian. 2010. ‘The Tortoise, The Scorpion and the Horse: Partial Notes on Architectural Research/Teaching/Practice’ in The Journal of Architecture, Vol.8 No.2, p.188.

[14] Spooner, Michael. 2013. A Clinic for the Exhausted: In Search of an Antipodean Vitality – Edmond and Corrigan and an Itinerant Architecture. Baunach Germany: AADR Spurbuchverlag, pp.47-48.

[15] Spooner, Michael. 2013. A Clinic for the Exhausted, p.26.

[16] Foucault, Michel. 1986. Death and the Labyrinth: The World of Raymond Roussel, trans. Charles Ruas. London: Continuum, pp.15-16.

[17] Deleuze, Gilles and Guattari, Félix. 1994. What is Philosophy? New York: Columbia University Press, p.209.

[18] Irigaray, Luce. 1996. I Love to You. London: Routledge, p.109.

[19] Deleuze, Gilles. 1988. Spinoza: Practical Philosophy, trans. Robert Hurley, San Francisco: City Lights, p.89.

[20] Grosz, Elizabeth. 2010. ‘Feminism, Materialism, and Freedom’, in Diana Coole and Samantha Frost (eds.), New Materialisms: Ontology, Agency, and Politics. Durham, NC, and London: Duke University Press, p.140.

[21] Bennett, Jane. 2010. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham, NC, and London: Duke University Books, p.365.

[22] Haraway, Donna. 1988. ‘Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspectives’, in Feminist Studies, p.588.

[23] Haraway, Donna. 2007. When Species Meet. Minnesota: University of Minneapolis, p.3.

[24] Bennett, Jane. 2010. Vibrant Matter, p.23.

[25] Deleuze, Gilles. 1998. ‘Literature and Life’, in Essays Critical and Clinical, trans. Daniel W. Smith and Michael A. Greco. New York: Verso, p.2.

[26] Deleuze, Gilles. 2002. ‘Description of a Woman’, in Angelaki: Journal of the Theoretical Humanities, Vol. 7 No. 3 (December), p.17.

[27] Deleuze, Gilles. 1993. The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque, trans. Tom Conley. London: The Athlone Press, p.19.

[28] Stengers, Isabelle. 2005. ‘Introductory Notes on an Ecology of Practices,’ in Cultural Studies Review, Vol. 11 No. 1 (March), p.186.

[29] Haraway, Donna. 1988. ‘Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspectives’, in Feminist Studies, pp.580, 582.

[30] Stengers, Isabelle. 2005. ‘Introductory Notes on an Ecology of Practices,’ p.187.

[31] Brünner, Margit. 2011. Becoming Joy: Experimental Construction of Atmospheres, PhD by Major Studio Project, School of Art, Architecture, Design, University of South Australia, p.19 and n.18. Available here (Accessed 15th September 2013).

[32] Margit Brünner, email correspondence with the author, 24th September, 2013.

[33] Brünner, Margit. 2011. Becoming Joy, p.153.

[34] Stengers, Isabelle. 2010. Cosmopolitics I, trans. Robert Bononno, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, p.58.

[35] Stengers, Isabelle. 2010. Cosmopolitics I, p.58.

[36] Stengers, Isabelle. 2010. Cosmopolitics I, p.68.

[37] Deleuze, Gilles and Guattari, Félix. 1994. What is Philosophy? pp.35-60.

[38] Haraway, Donna. 1988. ‘Situated Knowledges’, p.588.

[39] Varela, Francisco. 1999. Ethical Know-How: Action, Wisdom, and Cognition, Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

[40] Guattari, Félix. 2000. The Three Ecologies, trans. Ian Pindar and Paul Sutton. London: Athlone Press, 2000; Bennett, Jane. 2010. Vibrant Matter, p.113.

[41] Thrift, Nigel. 1999. ‘Steps to an Ecology of Place’ in Doreen Massey, John Allen, Philip Sarre (eds.), Human Geography Today, Cambridge: Polity Press, p.297.

[42] Latour, Bruno. 1993. We Have Never Been Modern, Cambridge Massachusetts: Harvard University Press; Haraway, Donna. 2007. When Species Meet.

[43] Haraway, Donna. 2007. When Species Meet, p.23.

Figures

Banner.

‘The Landscape Room’, Clinic for the Exhausted. Michael Spooner, 2010.

01.

RMIT University Building 8 Becoming Boat. Clinic for the Exhausted. Michael Spooner, 2007-2011.

02.

Schwebebild - Cosmethic Space Refinements. Pencil drawing, 45x63cm. Margot Brünner, 2002.

Schwebebild - Cosmethic Space Refinements. Pencil drawing, 45x63cm. Margot Brünner, 2002.

https://doi.org/10.2218/bmzvdy34