ABOUT

.jpg)

Surface and Installation

We will be uploading additional content shortly so please check back here for updates. A full copy of Issue 02 will be available to download soon.

ARTICLES

-

CS

Call for Submissions

Editors

Pavilion for Vodka Ceremonies. ArtKlyazma Art Festival, 2003. Courtesy of Alexander Brodksy.

Through a simultaneity of immersion and separation, Surface and Installation create multiple worlds in the same space. They make worlds of their own physical parameters; they remake parts of the world within which they sit, and hence it might be said that they can also at least point towards a remaking of the world beyond. Surfaces and installations are capable of impressing upon one space another spatiality and temporality. They make situations both in their own right and also as referents to the situation of the world. They transpose one situation into another. Surfaces and installations intensify the here and there.

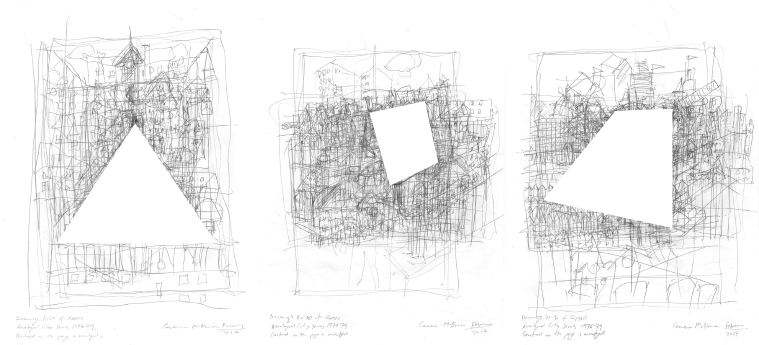

Concerned with architectural research-by-design methodologies, how we surface and install and how we record surfacing and installing are as significant to our research practices as the product of such actions. The recording of situations, within and without the space and time of surfaces and installations, is key to extending critical enquiry into critical methodology. There is, therefore, an intrinsic question of ‘drawing’ associated with both surfaces and installations, drawing not necessarily in the conventional sense but a drawing out – both in advance and in retrospect – of our relationship with the world.

We suggest an installation can be understood as a drawing where 1:1 spatial and temporal parameters move beyond that of a Euclidean surface. However, we also suggest that through drawings – the drawing surface as surrogate for the surface or slice of the earth – we might mediate the spatiality and temporality of surfaces as installations. Hence, the drawing surface is similarly charged with a here and there. It is both surface and substrate. It is an image-surface: an image as a drawing of situations. Drawing surfaces record relationships within and beyond their own limit: upon, beneath or above their own surfaces, between situations. Therefore, drawing on surfaces and installations, we open questions of how to draw out the worlds of and between here and there.

This is one call on two distinct but interrelated themes. Working towards Issue 02 of Drawing On, we invite you to contribute on either or both themes of Surface and Installation. We are particularly interested in contributions that explore ‘surfacing’ and ‘installing’ through design-led research practices and as acts that draw out the situation of the world, multiple worlds, critical views of the world. Depending upon submissions, the editorial team may make a multiple thematically organized edition. The submissions can be documented and recorded in various forms and formats; text need not be the principal means of presenting the work.

For submission details see the Submissions page. For previously published examples visit the Issues page. Submissions should be uploaded via the Contact page by Friday 28th October 2016.

Launched 1st September, 2016. -

PL

'Space Drawing': A Conversation with Alexander Brodsky

Alexander Brodsky, Mark Dorrian & Richard Anderson

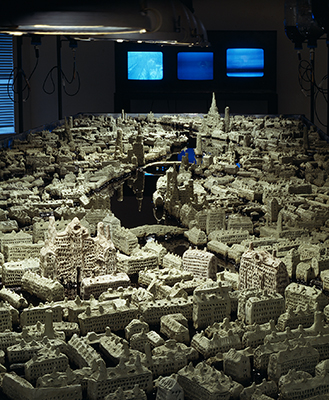

It still amazes me that I became an architect (exhibition). Architekturzentrum Wien, Vienna, Austria, 2011. Image by Yuri Palmin. Licensed via Flickr Creative Commons.

This discussion was held in April 2015 on the occasion of Alexander Brodsky’s visit to the Edinburgh School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture as George Simpson Visitng Professor. It is presented here as a prelude to Issue 02 of Drawing On, exploring the related themes of Surface & Installation.

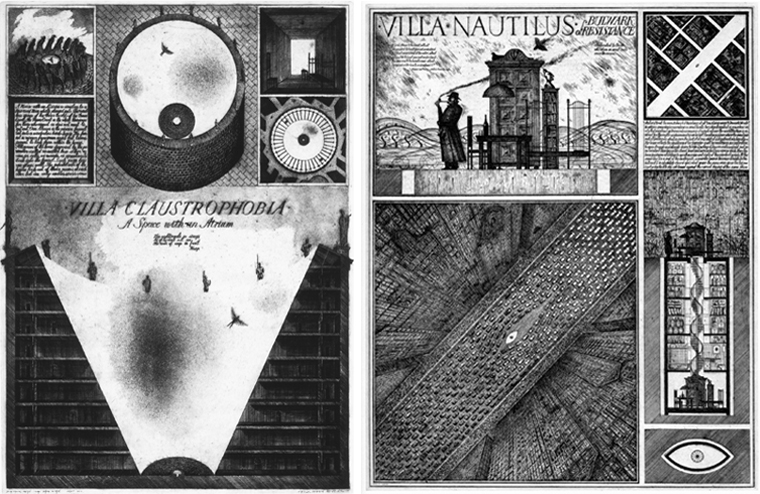

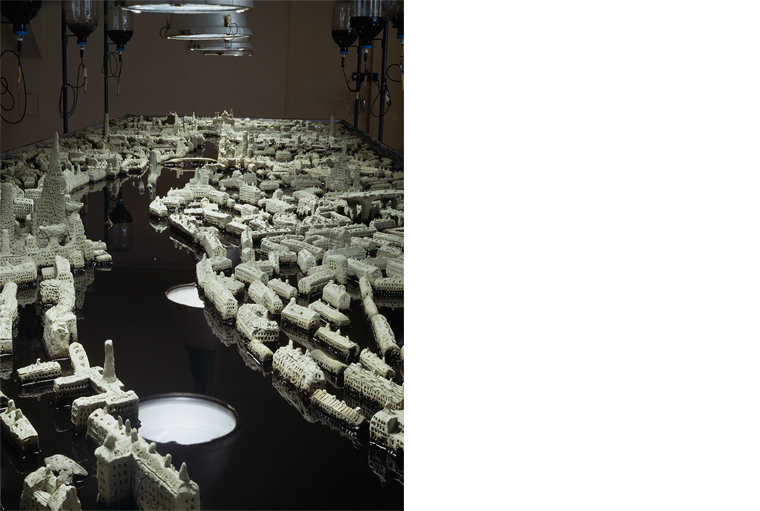

Mark Dorrian: This is not a very structured interview set-up... but we thought it would be very nice to be able to talk around the work a little bit. And I suppose one of the things that I wanted to ask you, something that has always been in my mind about the work, is that in a lot of the projects I see a kind of interest in depth. It's in the early works, such as the Villa Claustrophobia or the Villa Nautilus, with its depth condition down into the subterranean. Or in a way, it is there in the skyscraper, the glass tower building, as well as the high, or deep, sectional condition that we see in the glass bridge in the mountains. I think it is there in quite a few of the installations – so things like, again, the Vienna installation, with the reflection, where you use the oil and the light coming from above to produce the effect of a deep, vertical condition. I also think it is reinforced by the format of the etchings that were published in the Brodsky and Utkin book – they're almost always portrait as opposed to landscape orientation. I wonder, well, first of all, if you think the observation is correct, and then if you have any thoughts about where that particular interest in the deep, sectional condition comes from.

Alexander Brodsky: Yes, this is correct. The depth is really an important thing for me. So, when I was making etchings – this is kind of a mysterious technique – depth, really on a fair piece of paper, when you have to press the drawing, you see it gives you the feeling of really deep space behind the paper. I don't know how to explain it. For me it is always mysterious. And this is what happens with etching. Partially that's why I was so concentrated – concentrated on the etching technique. Every time that I press the paper it is a wonderful feeling that even if you don't like the drawing itself, it still has some space inside. In the installations, probably I don't think about it, but it happens mechanically. I am trying to keep this feeling of the drawing, the etching, in the three-dimensional work. So, I can say that I'm trying to bring the depth of the etching to the three-dimensional pieces. And it's not easy. Sometimes I just fail, but sometimes it's working.

left: Alexander Brodsky & Ilya Utkin, Villa Claustrophobia, 1985-1989. From Projects portfolio, 42 x 31 inches. Photograph by Hermann Feldhaus, courtesy of Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York.

right: Alexander Brodsky & Ilya Utkin, Villa Nautilus, 1990. From Projects portfolio, 42 x 31 inches. Photograph by D. James Dee, courtesy of Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York.

Richard Anderson: Can I follow up on that? Do you see that kind of exploration of depth that you're describing between, you know, the etched plate and the paper also reappearing in some of the more recent work? I'm thinking of the clay reliefs that are shown at your current Berlin exhibition. Is that part of the same exploration?

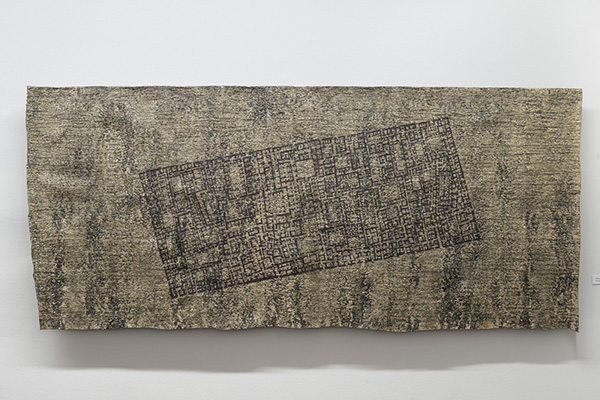

AB: I think so. The flat reliefs, because of the texture, have this feeling of depth although the clay surface is quite flat. But probably, partly because of the cracks that are unpredictable, it gives the feeling of a drawing when you come close. It's also the effect of the difference when you observe it from the distance and then you come very close and see tiny details. I like this feeling very much – the closer you come, the more you see. And of course this Vienna installation, with this reflection, is also an attempt to bring the quality of etching into big scale, three-dimensional work. So, it's kind of a drawing. Space drawing.

MD: I hadn't appreciated that before, but absolutely – because when you talk about etching, we also think about the ink and the reservoir, you know, and the relationship between the plate and the imprint. So etching is a kind of doubling, as well – first of all the drawing is doubled in the engraving, but then the image from the print doubles in a reverse way the engraving. So when we see the Vienna installation, we think about the etching and we think about the oil reservoir, the pool, the doubling of the reflection, the relations... and there's this interplay between flatness and depth. The relation seems very strong.

RA: Following on that, one of the things that strikes me about so much of the work is precisely this relationship that I think you're describing, between what you see at a distance and what you see up close. And it seems that a lot of that has to do with the texture, you know, the texture of the image – whether it is the print from an etched plate, whether it's the texture of the clay that's drying in unexpected ways. And I wonder if you could talk a little bit about this texture, because it seems to be a great focus of the work, whether it's the texture of the lines, the drawings, or the texture of text that is part of so many of the images. Do you feel that this relation between near and far, when you observe the images, is part of the work?

Untitled (unfired clay) from the Facades exhibition. Triumph Gallery, Moscow, Russia, 2013.

AB: I think you're right, yes. Like this text, from the distance it's just a spot. When you come close you see it's text. But in the etchings, its role is just one of the spots in the whole composition, I think... I don't know if I'm understandable [laughs]. So, yes, that means I try to use everything to make this etching deeper. And you're right that these letters within this composition forms some dark spots – and then you can see that you can read it, and it gives another sort of depth.

RA: One of the things that strikes me just now, which I hadn't thought of before, is the way that so many painters have used text – you put text on the surface of a painting and it automatically almost creates a depth behind the picture plane. And I can't help but think of some of Malevich's early paintings – An Englishman in Moscow, for example – with these kinds of devices. Do you feel like those kinds of traditions are at work, maybe consciously or subconsciously, in this textual relationship?

AB: Well, I don't think that Malevich really influenced me, although I like his work very much so maybe I don't understand it but somehow it goes into my works. In the etching series I was mostly, of course, influenced by Piranesi, who is really the champion of depth. Several years ago I was at an amazing show of his work in Venice. You probably heard about this exhibition. I especially went to Venice with my son to see it. It was a huge exhibition of all his prints together. I knew most part of these images already, but it was completely different from the book because it was crazy deep, every picture. And they made an incredible thing for this exhibition, a very nice animation of his Prison series. There was a big screen and you could fly through these spaces from one picture to another – and they really made it look like one huge space with different rooms, and so you were flying here or there. It was very nice.

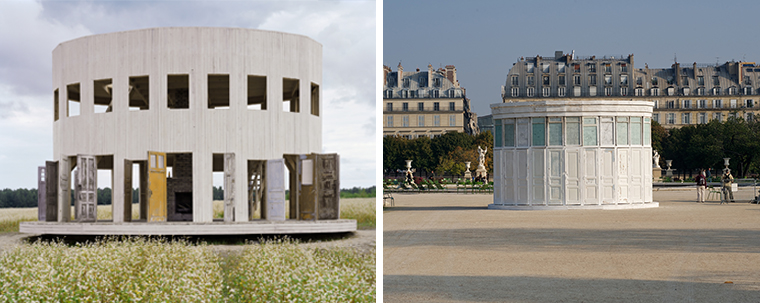

left: Rotunda. Kaluga Region, Russia, 2009.

right: Rotunda II. Tuilerie Gardens, Paris, France, 2010.

MD: Again, I think an important aspect of the etching process here is the fact that material is literally being removed – you know, the plate is being worn away by the stylus in the act of engraving, and then by the acid that eats into the exposed metal. And this makes me think of reused objects in your work, and the importance of materials that are worn, that carry the textures and traces of previous uses, such as the doors in Rotunda (2009) for example, and how they seem to have something of the same quality of the etching. They almost seem etched themselves – etched by the history of... [AB: By time] Yes, by time. You know, there is almost a kind of sympathetic relationship between the process of etching and this use of worn materials and artefacts, and this seems a way of transporting the qualities of the etchings into the constructed work.

AB: Yes, you're right. Using these old things like doors and windows – I do it not only because they are beautiful, but also because they really give depth of time to the structure. One door can say a lot of things, and you can feel how old it is, how many times somebody opened and closed it. Every piece has an amazing, interesting history. It's probably not a good way to work, but... [laughs]. It's maybe too easy to use this thing for giving depth to the whole structure, but it works perfectly.

MD: And it produces a similar visual effect, a visual relationship between the distant and the close – a reading that, I think, works in a comparable way to the experience of the engravings...

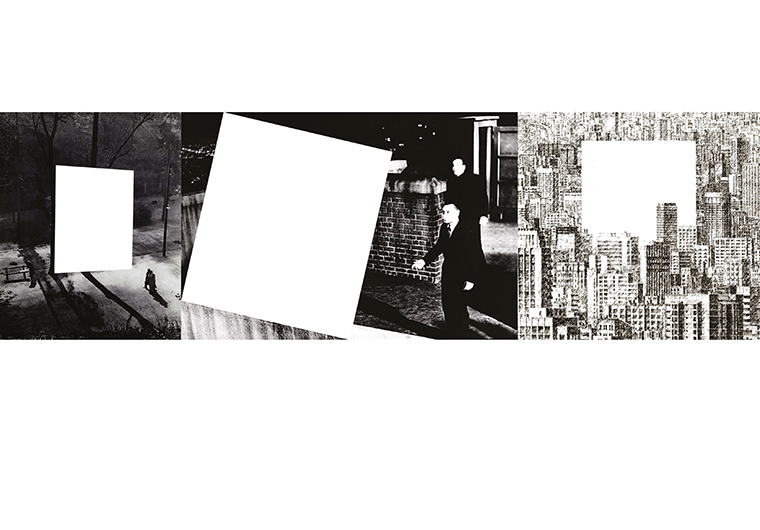

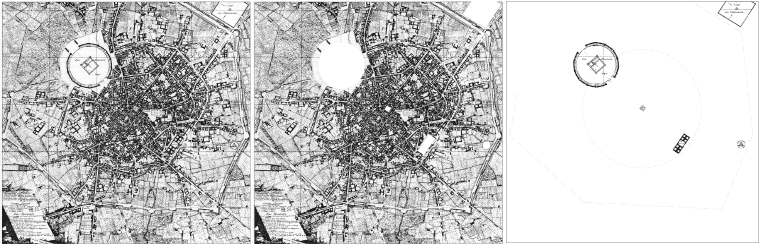

Could we talk a little bit now about the city, and about cities, in your work Alexander? In the early work – that published in the Brodsky and Utkin book for example – the presence of the city, and of the city as an almost imaginary site or location for the project such as we see in the Villa Nautilus project, seems very important. I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about the city as a site of the imagination in this work, and how it might relate to specific cities of your experience?

AB: It's a very important thing for me. I was born in a big city and grew up in a big city. So it's somewhere deep in my body, the spirit of huge city. I have lived there all my life, except for years I spent in New York, which is even stronger, in this way. So, of course, the big city is an important part of almost every drawing, like in this competition series – a lot of city images. And, in some way I see this, it's a mysterious thing, every city. A lot of mysterious things you can see, maybe not from the first moment, but then there are also a lot of secret spaces that you probably never see, but you know are there – like the huge spaces below the streets in Moscow, built around a hundred years ago or in Soviet times, for some military reasons. A lot of them are not in use so it's quite difficult to get there, but people know that they exist. In some way I saw life in a big city like life in the forest. You know some roads and some places, you know the road to your friend, to the other friend – there is a number, sometimes a very big number, of ways you use. And this reminds me of one little house, the other little house, and the forest. You go this way, you come to your friend, and from there you go to some other place. This is a big part of life in a big city.

RA: That's a beautiful image of a city as a kind of mental landscape, if you will, but it also has a narrative element to it, something fantastical as well. I wonder if I could ask something about some specific images, some specific cities, which also seem to appear in much of the work and that have a similar quality. I'm always struck by the echo of Venice, you know, and the gondola – the kind of city with rivers running through it. I mean, how important is that imagery, or that specific place as an idea, to the work?

AB: Well, it's quite important for me. I don't know why, but a long time before I first visited Venice I had this image, the image of the river together with architecture. It's really important for me. I made large number of drawings about the river, which is constantly moving, and then the architecture is always standing in one place. And this combination of something moving and something stable – this is an important thing for me. When I first visited Venice it looked exactly as I had imagined – almost no surprise. Of course, it was a big surprise altogether, but this feeling of buildings standing almost upon the water is a very strong thing.

And, talking about this forest, I just remembered that there's the image that I always have in my head from when I was a little boy. I read this wonderful book “Winnie the Pooh” by A.A. Milne, and they have this funny map. Each of them lived in the trees, in the forest so they go to this friend, they go to that one – and this is a kind of inspiration for me [laughs].

MD: I think it's interesting as well, because Venice is a city that is, above all, a city of the imagination – one from which other imaginary cities are generated. I suppose we think of something like Italo Calvino's Invisible Cities, for example, in which it turns out that the protagonist, Marco Polo, who is supposedly describing the cities within the Great Khan's empire, is in fact re-describing Venice every time. So it's a city that seems to imaginatively generate incessantly other cities. It's also the city that is most characterised by doubling – it's the city and its reflection; or the city between sea and the air, between Hermes and Neptune; or between earth and water (the Lion of San Marco with its feet on water and on land). So, it's a city that seems to generate narrative and stimulate imagination – it has played that role. But in terms of the specific figure of the gondola itself – it is certainly a very strong emblem for Venice, but it's also a mythic object as well, one that might carry connotations of the dead – of crossing over to the space of the dead. There are certainly depictions of Venice, which show the gondola in this way. I'm thinking of a painting of a Venetian night scene by John Wharlton Bunney, a nineteenth-century artist that Ruskin knew well. In it, the gondolas are like – well, you know, they are from the underworld, crossing over to this other place. Which makes me wonder about the quality of the silhouette. So in the Canal Street project in Manhattan (Canal Street Canal, 1997), whenever you make the gondolas, they're silhouettes, they're... [AB: Flat, flat gondolas] shadows. And I was wondering if the mythic quality of the boat, or the river, as a threshold between what is here and what has passed, between life and death, had particular consequence for you?

Coma. Marat Guelman Gallery, Moscow, Russia, 2000.

AB: Yes, yes, this is what I mean. This river, it's quite... every time it's a very symbolic thing. It's a kind of obvious and banal thing, but still, it's like this. It's a symbol of time, like a visible piece of time that's always moving, and it changes the surroundings. So the river's always the same, but what's standing near the river is changing – ruining, disappearing. New things become built on this space, but the river is always the same.

RA: I was struck by this particular image, a print that was on display in Berlin in a recent exhibition, which includes both the gondola and another motif that I think appears in many of your works – an empty chair, often within an enclosure. I think of the recent bus shelter in Krumbach in Austria, for example, which is also the kind of large chair that is in the enclosure on the gondola. One has a sense that maybe this idea of sitting in chair, protected, awaiting something, has something to do with the experience of time? Is that part of what you're thinking?

Bus Stop. Krumbach, Austria, 2014.

AB: Sorry, I don't understand.

RA: So, the gondola is on the water, which evokes a kind of passage or experience of time, and then there seems to be a place on the gondola, which is prepared for somebody but is empty and absent – but it's also somehow protected, you know, in the cage... [AB: Yes.] And I wonder if that is about a kind of specific relationship to the passage of time?

AB: Yes, in some way it is so. The chair is empty, and this is an important thing, as you said. So it's a place for Charon to cross the river... but he left [laughs].

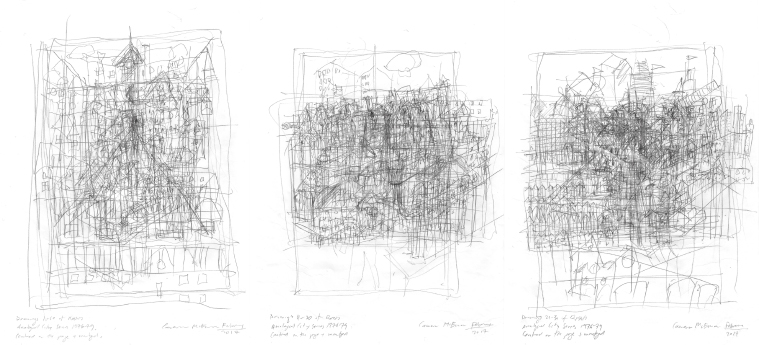

MD: So it's the ferryman himself who has left the chair? That's interesting. I wanted to ask you, Alexander, about what might be described as the allegorical aspects of your work. I'm using this to refer to a kind of work that stands for something else – a story or a condition – but not in a direct way, so an effect of opacity is produced. So, we think of works that use particular kinds of symbols or stories or narratives for talking about things in an obscured way. There's always a certain mystery or enigmatic quality – it's something in it's own right, but at the same time we also feel that there's a depth or consequence behind it that we struggle to grasp. So, there's a kind of burden of interpretation, I suppose, around the allegory that we have to bear, without ever feeling that we arrive at a complete and satisfying interpretation of the work – instead we always feel that we're involved in a series of attempts at interpretation. Certainly, in looking for instance at the Villa Claustrophobia drawing, for instance, I feel a sort of interpretative challenge – is it about the predicament of the individual in relationship to mass society, or about a certain condition of vertigo, or about the city and fantasies of release from it? I haven't been aware of the term allegory being much used in the way people have written write about your work, and I was wondering if it was something that you had considered or if it has any consequence for the way that you think about the work?

AB: Oh! Well, I'm not sure I'll answer the question, but it's a very important thing for me – the mysterious part of architecture. I am talking about the drawing and the building – the real building. It's very hard to explain, but all the buildings that I really like have some mystery, for me. It's not like I understand everything. There's a lot of buildings that I don't understand: how they built it and how could an architect design such a thing. And what did he mean? With some buildings you see it, and you know immediately what it is, and how it was built. I don't know, maybe it's not a good example, but I come to a big supermarket and although I don't know everything about it, generally, philosophically, I understand it. But when I see a palazzo in Rome or in Florence – I can come close, I can touch it, but there is a big, big mystery for me. And even in some contemporary architecture I see examples with this quality. For me, the works of Peter Märkli are in this part of architecture. Sometimes it's very simple, absolutely, but I feel something mysterious as in the famous museum of sculpture that he built – it's full of mysterious qualities. Although it's just a kind of absolutely simple concrete box, when you come near you can feel something very strong about it. It's a very mysterious place. So it's hard to explain, because it's to do with intuition. But for me it's very important. So of course when I draw architecture, I am trying to give this feeling – you're not quite sure of what it is. You like it maybe because of the graphic and compositional and some other qualities – the quality of etching; but at the same time, generally, there's something not very clear. You want to ask something about it. So you're thinking about it – you ask questions to yourself, you look for the answer.

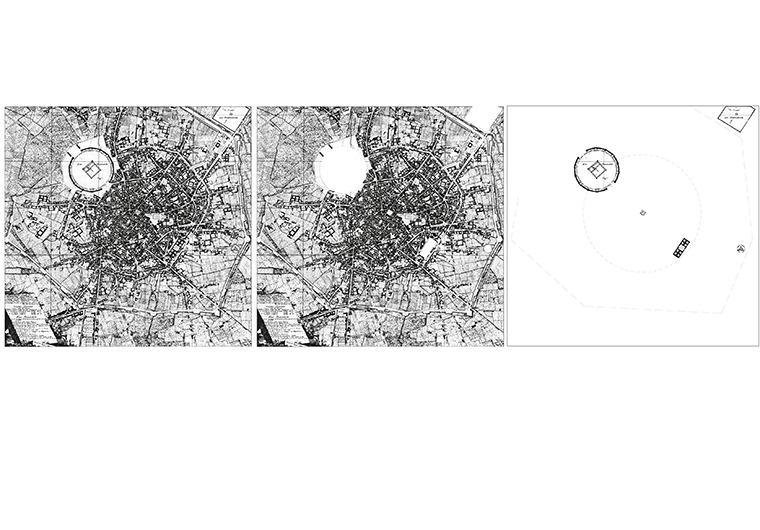

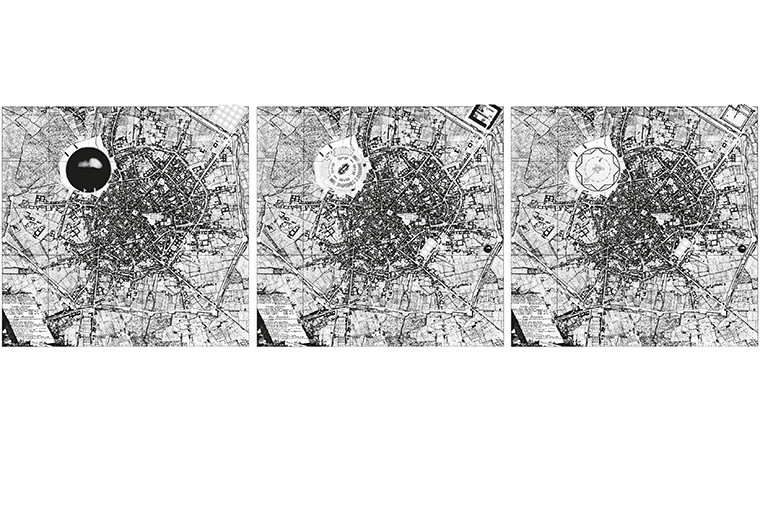

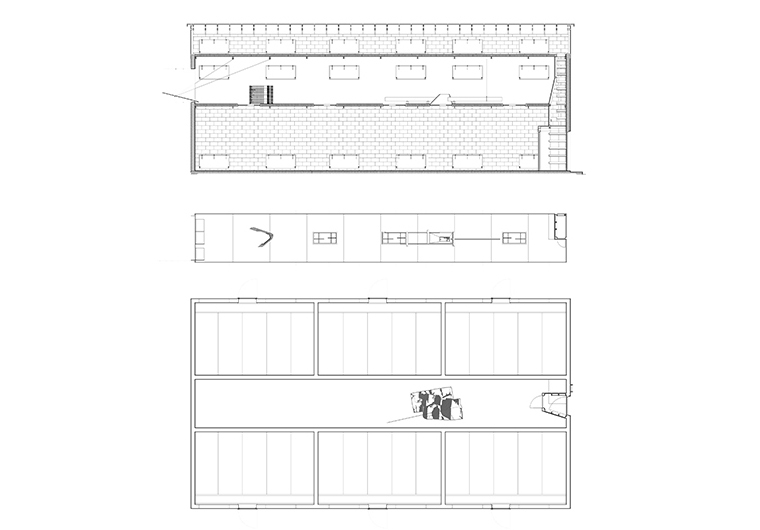

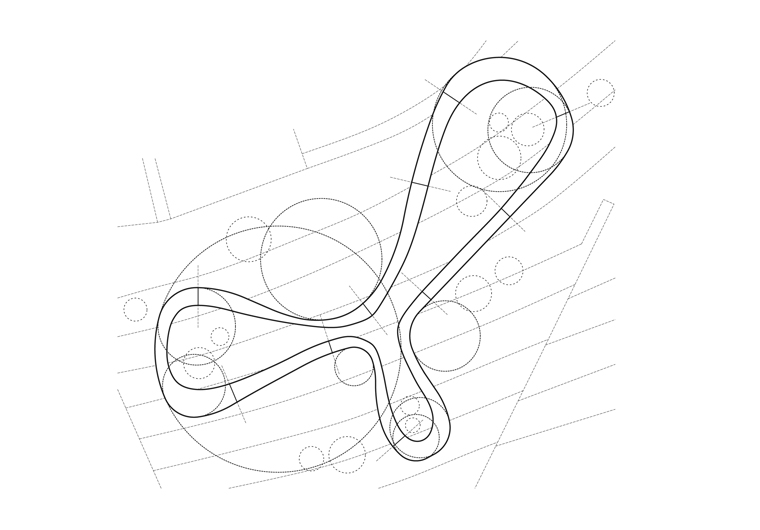

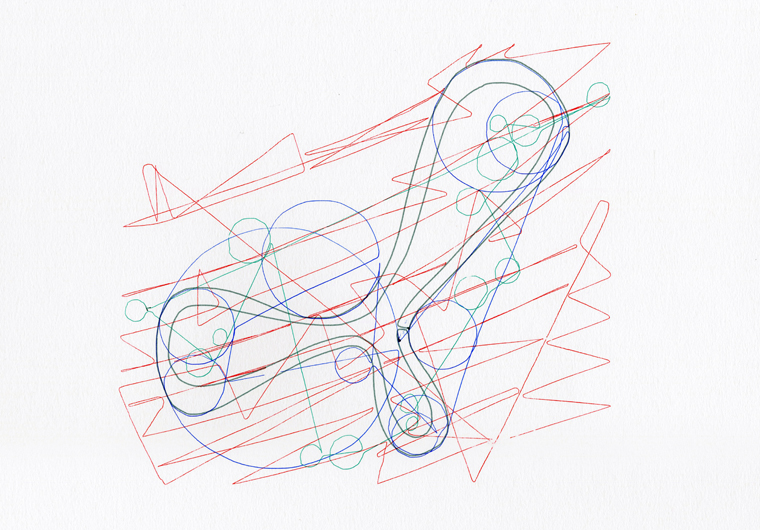

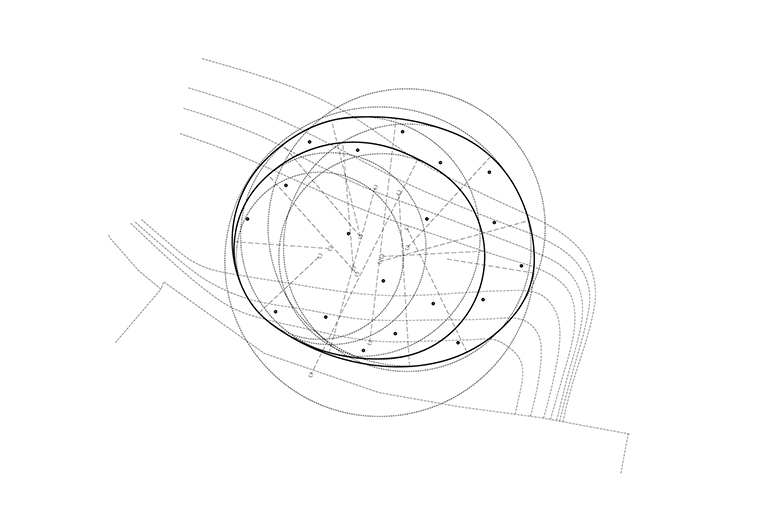

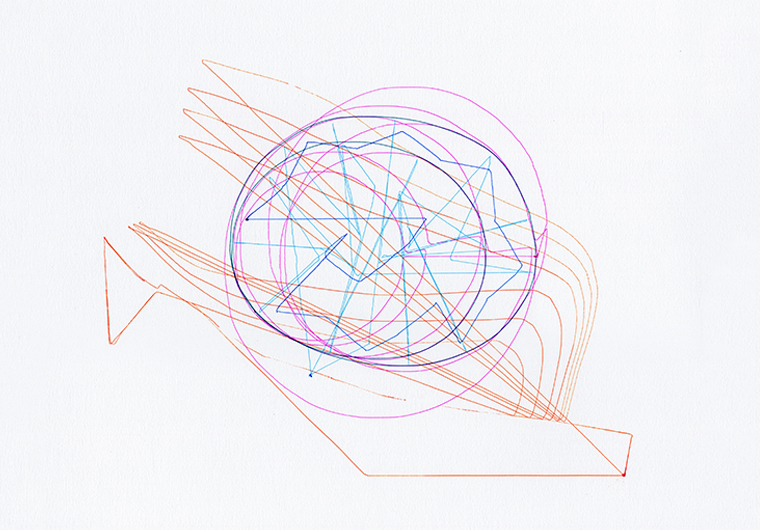

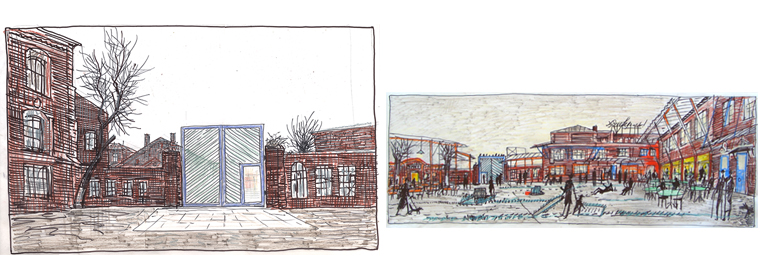

Sketches for the Vinzavod project, Moscow, 2007.

RA: I was going to ask about these mysterious qualities. One of the things that strikes me, for example in, say, Vinzavod, the wine factory in Moscow, is that is has this incredible mysterious quality. I've read about it, sometimes, as a very nice preservation project, so as not to demolish it, but was the intention to preserve this mysterious quality of the original structures there?

AB: Yes of course. We try to keep as many things as possible. Well, firstly it was not possible to destroy it, to build something new, because it's a monument – it's historical heritage. So even if you wanted to do this, you couldn't. And of course, we didn't want to do that. We wanted to just use the space, make small additions, but keep the whole atmosphere. However, in some way, we didn't do this. There are some places that I am not satisfied with, but generally... We didn't finish the project unfortunately. This was a very sad experience because we made a big project and then the realization was stopped at some point because they changed their mind. They didn't have enough money, so it was half-made. This is how it exists... for several years. But still, I'm glad we managed to keep some places absolutely the same, although they're used for some little institutions... but basically it's the same. We added some small, small, almost invisible things to adjust it to this art centre.

MD: Are stories important in the work, Alexander, stories told about the project – but perhaps about the spaces in which the projects appear?

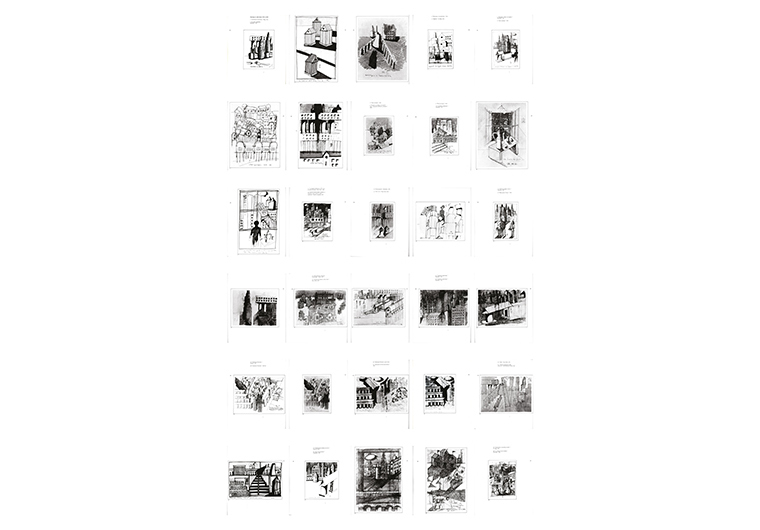

AB: Yes, we can talk about this series of competition entries. It of course consists of many different components, and literature is one of them, so we used sometimes pieces of poetry when it really explained the idea, and put it there. Or a little text, right there, usually very short. But another thing that needed to be done in this competition was to put all the sense of the project in not more than a hundred words, which was one of the rules. So, even if we didn't want to do this, this task to keep it, to make a very small text with a lot of sense, gives some poetical quality.

MD: Yes, the projects seem at times like a kind of folklore, a kind of contemporary folklore about the city. So, the story of a man who lives in the middle of a road, for example, or a man who lives underground. They're kind of emblematic individuals or conditions which, although they're told about contemporary conditions or urban situations, seem connected to an old tradition of storytelling as well.

AB: Yes, I even call them architectural fairy-tales... so, the fairy-tale is always behind...

MD: It makes me think of Chagall, you know, Marc Chagall the Russian painter... [AB: Yes, of course, of course] with these magical peasant scenes – animals and...

AB: Yes, in some way... I was very much inspired many years ago when I first saw Fellini's 8½ and this strange structure in the air with no use, just a beginning of something that never happened. This was a really big influence, an influential thing for me, for many years.

MD: Do you see yourself as part of a Russian tradition or would you avoid describing your work in that way? Is there a sense of strong inheritance? Certainly in your lecture last night you spoke about the houses on the outskirts of Moscow and a kind of everyday vernacular that is disappearing with the construction of new apartments and other buildings. So I suppose maybe that's one sort of specific relation – but in terms of a longer history of Russian literature or art or architecture, do you feel strongly part of a tradition like that?

AB: I don't know... although the work was made in Russia. It is Russian, but it's not some exact tradition that I take from... I think it's something else. What was really important for me, which influenced me very strongly, is the poetry of Joseph Brodsky. The first time I read it, I was really amazed by his poems, and somehow, since that moment, they really influenced what I was doing. And in some of his poems he has this amazing combination of antique Rome and contemporary things. So this was important for me.

RA: One of the things that I wanted to talk to you about is the way the work you're doing right now, both with the architecture practice – designing and building buildings – and also the kind of work that was shown recently in Berlin, is linked. Do you see those as connected or separate kinds of your work – you know, on one hand the continued etching and the making of reliefs and installations and, on the other, the architectural work? What is the relationship is between those? And then, how you see the work that you're doing now in relationship to some of the earlier conceptual projects with Utkin? Do you, for example, feel you're pursuing some of the same things? Do you see your work kind of branching out into slightly different territory, with the built work and then the work that has more of a fine arts quality?

AB: Well... I guess this is my main problem in what I'm doing, because it's still divided in two parts: the artistic part and the architectural. When I make some small temporary pavilions I'm absolutely free and this part of architecture – if we can call it architecture – is strongly related to these etchings and conceptual projects. It's definitely part of it. But when I'm making someone's commission, like the living house, it becomes really difficult. I always think that now I will make something related to this artwork, but I don't think I am very close to it... it's still far. It's very difficult, because I start working with a client and eventually this is also, always, a competing thing – the architect's ego. This is a banal thing, nothing new, but still... the architectural ego of the architect who wants to make something extraordinary that will be published in a magazine. But to make simply a comfortable space for living for these people – this is always more important for me. I think about this family, go into the small details of their life. I know their kids and I design special rooms for them and if they don't like something that I want to use, if they really don't like it then I don't use it. I know a lot of examples when the architect wanted to do something, and then the people who were going to live there they have to, somehow, adjust their lives to architecture... and it doesn't always work. I know examples when the architecture is a beautiful thing, very unusual, but it's not possible to normally live, to normally live inside. And the clients started, sometimes, and when they couldn't live in it, they sold it to other people – and maybe the other people are OK there, or not. So this is a very difficult thing – a problem for an architect. And it's still divided for me. Some houses that we build are much closer to this quality, but some are not. The nice life of the client is always more important – so I go so far in these details that sometimes I forget about the artistic quality [laughs]. It's hard to keep everything in your mind at the same time – a structurally good project, safe and comfortable, and at the same time architecturally interesting.

RA: How does this relationship between the ego of the architect, the ambition of the project, and the client play out in some of the commercial projects you've worked on? I think of the 95 Degrees restaurant or interiors like Ulitsa OGI (both 2002) and these other places. Do you feel you've had more room to explore some architectural themes in those kinds of projects?

95 Degrees. Pirogovo (Klyazma Reservoir), Russia, 2002.

AB: Yes, of course. Like this restaurant, it was for me definitely not a commercial project, it was a kind of sculpture. But of course, I thought about the kitchen and the tables, and people going back and forth, but here I really think I was successful in putting some art into an architectural project. And it is the same thing with the interiors of these clubs and cafés, a few places that were made in Moscow. The clients are my very good friends and here it was interesting because they usually call me and say: “We rented a really depressing basement... [laughs] and we don't have money. But we need something extraordinary, cosy and nice for people.” This was an interesting thing – no money, terrible basement, so I had to invent something. And we did these places and they were really popular – a lot of people were coming. Until it was closed. So this is easier but when you meet people and they want to make a four-bedroom house, it's much more difficult.

MD: But this is interesting. Thinking about the work that you showed in the lecture, there are, on one side, the speculative projects and the installations, and then on the other there are certain building projects – but there's a category in the middle, in which the two really seem to come together very strongly. And they seem to do that partly because they are temporary, they are understood as temporary constructions – but of course often temporary constructions turn out to be more enduring than supposedly permanent ones. So we have... well, there's obviously the pavilion for the vodka ritual; there's the rotunda with the doors within the landscape; there's the 95 degree restaurant as well. All these are under the sign of the temporary – and because they're temporary, the stakes change a little bit. Some things perhaps become possible; or maybe the regulations get a little bit looser; or things become, you know, negotiable in a way that they would otherwise not be. And I think that's a very special zone of the work, a very special point at which the architectural and the art practice come together in a powerful way. And somehow, because these are coded as temporary – whether they're temporary or not, I mean: they may be more permanent than any – it allows a kind of space for these aspects to meet.

AB: Yes, maybe this is one of the ways to do nice things – to make them temporary, but strong enough to be more permanent [laughs].

MD: Yes. In Paris we can still see Le Corbusier's L'Asile Flottant, the Salvation Army barge, which was temporary, but which is still there and has outlived many of the so-called 'permanent' projects.

Could, we talk a little bit about clay as a material, and importance of clay in the installation work?

AB: Yes, of course. You can see it's a very important material for me. I started working with clay many years ago, when my friend and I received a commission to make a big sculpture for some museum. And at that time we were working in a big sculpture factory, and clay was used as a first model, as a temporary thing; then they would make the plaster mould, and then cast it in plaster, and then take this to the other factory and then make the final thing in bronze or stone. So the clay was the very beginning and they always used it, because one of clay's amazing qualities is that you can make anything, dry it, and it will be quite a finished thing – but then you put it in water and it's clay again, so you can use one piece of clay ten thousand times for different things. For me it was really conceptually very interesting. I saw how they make clay monuments – huge Lenins and soldiers, and all these sort of things – and then they take it apart, add water, mix the clay again in a big machine, and then another sculptor would take it and make another Lenin [laughs]. So I wanted even to make some installation, based on the idea that this clay sculpture could be Lenin's ear, or his foot, or his head. And then it could be the soldiers' weapons – and now I make some other strange thing, but maybe in some time it will become something different. So this is one quality of clay.

The other is that it's really easy to work with. It doesn't resist at all – unlike stone, unlike making engravings, or things like that. Maybe it's not very good, but if you keep this strange feeling – that you can take this piece of clay and make it whatever you want, any object, very easily, then it dries and it exists like a sculpture, very fragile... like dust. So this feeling that everything that I make can become dust and then clay again gives some interesting effects. And this is partly why I like to work with it. And, well, the first man was made of clay [laughs] so it's also a very important material. But I see objects made of clay, without firing, they always give this feeling of temporary life – everything is temporary. And this is a kind of symbol of time, for me. And, visually, I think it's very beautiful. When you fire the clay it dies. It becomes very hard and stable, but something important leaves it. This lively, strange thing becomes a pottery or some ceramic art but it's really different. So I made some... I fired pieces a few times. It was a commission to make something stronger. It was interesting how they came back, came out of the kiln – they were kind of dead.

MD: Yes, that's something to do with the quality of the surface as well, because when fired the surface becomes sealed... [AB: Yes, yes] and, you know, loses its sense of porousness.

AB: It is no longer... it stops breathing.

MD: Yes... that's interesting.

RA: That seems also to lose some of the mysterious quality that seems to interest you. When it's fired you know how it's going to exist. When it's unfired it will continue to age and crack, and change in its own right.

MD: It's as if, I think, we understand the clay object that's unfired as something provisional or contingent, or that even might be destroyed or sacrificed in making of a 'permanent object' – as in the tradition of beginning in clay sculptures that will turn out to be bronze. To make something in clay monumentalizes it – but in a very contingent and provisional kind of way. So in the Grey Matter (1999) table, for example, where we have, you know, a toy rabbit or a sewing machine or a smoothing iron or a woolly hat, all domestic and familiar objects that are placed together, we see them in a different way because of the material transformation – but it's not as if they're cast in bronze or something, it's not as if they've become fully monumentalized. Instead, they've become frozen, represented in a very contingent way. In a sense, we feel, not that they're permanent, but that they've been made more fragile and precarious by the making. I think it's a very special kind of effect, which the unfired clay produces.

above and below: Grey Matter (installation). Ronald Feldman Fine Arts Gallery, New York, USA, 1999.

AB: Yes, yes – in some way, this is the material that can be used for making memories... as physical objects.

MD: Was it important when you were making the objects that they were approximately the same size as the things that you were remembering? So the sewing machine is about the size of a real sewing machine, and the toy rabbit is about the size of a toy rabbit, and the model of Pushkin is the same size as the model of Pushkin that you were remembering – or did they in fact transform in size as you were making them?

AB: No, all these everyday objects are the same size, more or less. Maybe with some mistakes, but basically, they're the same size, like the real objects. But of course I made some that were not from everyday life – like the Egyptian pyramids. The sections of these – it was just a beautiful thing for me, with a lot of meaning. And probably some other things – like huge glasses, among other objects, which were this big [gestures]. But mostly they were the same scale, like the real objects. And I made a lot of buttons – hundreds of different buttons because they're really easy to make [laughs]. But they're beautiful.

RA: The question of scale is interesting to me. In some of the recent work that, at least at first glance, seems to be less about architecture than landscape, there seems to be a shift in the scale of the graphic work. Do you sense a change in the scale of the kind of etchings that you're doing? Is that related to a different theme that perhaps you've been pursuing in some of this work?

AB: You mean if we compare the scales of etchings and... ?

RA: Well, I'm thinking of a comparison between, say, the some of the landscape etchings that were recently exhibited and the single-sheet etchings that were part of the early conceptual project series. There seems to be a different relation between the image and the size of the print. I wonder if you could talk about that.

AB: Yes, of course it's important, this play of scales – and it's one of the things that interest me. This comparing of something huge – like, I don't know, a galaxy – and the small detail. Well, it's also kind of an obvious thing but how they connect to each other... small details are very important for me. And of course when I make a button somehow I think how it looks like in the universe. Well, in simple words, the last installation – I made it very recently in London, about a month ago – was completely about this. It was in a basement, the Ambika exhibition space (University of Westminster). It's really high – about fifteen meters – a huge space under the ground, which was originally used as a laboratory for checking building constructions. For instance, using huge cranes they would take some big construction element and throw it on the floor. They would need this height. And then they left – for some reason it was not in use. And then it was transformed into an installation space. So I was asked to take part in this group exhibition – four artists – and I asked at the beginning that they gave me a big... well, it was just like a quarter of this space, and they wanted to use the height, because it is so unusual. So I made a plastic volume – not as big as I wanted because they decreased it a little bit – but still very big, very high like a huge cube about 10 meters high and 10x12 meters on the floor. And we put this translucent plastic that they use on the façade of buildings that are being repaired, this white plastic to make walls and ceiling so it was completely isolated from the others – one little door and even empty like this, it was really beautiful. You came in and it was like being in a church – huge, and this light coming through. And I put there five pedestals of concrete blocks and some models of ruined cities – not exactly, but some clay boxes with some walls inside and a lot of very, very tiny pieces, like ash, like ash everywhere. There were five of these things in the space, with the lamps, so the light was concentrated. It was a very low light... and these five spots were illuminated with little lamps, so you would see these very, very small clay things, like the walls, and inside the walls these kind of ashes, very tiny bits and pieces. And it was my idea to make people – but of course it was not enough, not big enough, but still it works. You concentrate on these tiny details, and then you see it is lost in a huge space. And it really worked, put together. But it is really impossible to photograph. I tried, but it is kind of fragmented in the photograph – you don't understand it. It may be good for video but I didn't have a camera with me.

MD: I wanted to ask about the work of John Soane and his famous... [AB: The museum] house museum.

AB: It's the most amazing place.

MD: Because I see, more than in any other example that I know of, a correspondence with your work – the interest in the compaction of those fragments as they appear in the museum [AB: Yes, yes], and also the way they are held within an architectural setting.

AB: Yes, I learned about this space about ten years ago, and then I was waiting for the moment that I could visit. And when we went to London, I immediately went to this museum. I was really astonished. So I think it influences me, of course, in some way.

And what is interesting, the man who founded this architectural drawings museum in Berlin, where my show is now, is a Russian architect – very powerful and successful, a very nice guy. Once we were drinking together, talking about architecture. I had just come back from London, and I told him about John Soane's museum. He never heard about it, but he said: “Well, I'm going to London very soon.” And afterwards he called me and said: “Thank you so much; because it changed a lot of things.” And that was the start of his idea to make this museum in Berlin. So in the beginning it was the impression of John Soane's house – and he was really strong enough to build this museum, which is incredible.

MD: For his lectures at the Royal Academy, Soane had these incredible models made out of cork. I was reminded of them when I saw the clay models that you have been making – the subsiding building, for example – and the quality and detail of their surface. Soane used cork, which is a very soft and pitted wood, because he wanted to convey the feeling of the temples as ruins, their breaking apart – and the effect is a little bit similar to the breaking clay... [AB: Yes] in the subsiding model. It feels like it comes out of a deep history. In a way the material feels already worn, as if it's carrying the marks of a complex history. But also this interest in the emotional or affective power of compressed fragments, which form a sort of dense architectural accumulation – one has the feeling of that very, very strongly in the way pieces are organised in the Soane museum. But also I think again of things like the Viennese installation (Architekturzentrum, Vienna, 2011) with the elements compacted upon one another, where it's almost like an archaeology of everyday life, or even a section through a waste or a refuse site. Or the installation that you made with architectural fragments in Pittsburgh (Palazzo Nudo, 2010). Or even the Grey Matter project, where the elements aren't spaced out in individual plinths, but become pushed together and jostle one another – they push and they drag each other because of this spatial compression that they have. It becomes hard to talk about them in terms of an order any more. It's not as if each one has a completely defined place that it might occupy in relationship to everything else. It's more as if everything is displaced and finds a surprising relationship. We find a pyramid beside, I don't know, a little Pushkin or Lenin's head, or something. It's like a strange dream, in which we find new relations between things...

It still amazes me that I became an architect (exhibition). Architekturzentrum Wien, Vienna, Austria, 2011. Image by Lorenz Seidler. Licensed via Flickr Creative Commons.

AB: There was another thing. I once used this installation, Grey Matter, for a commission, some time after the installation. It was interesting. I received a commission in Holland for some big, mental hospital for old people. They had just built it and, according to the law, they had some percentage of the budget for art. And it's a huge building, with a big atrium. There was a jury that consisted of half artists and half doctors and staff from the mental hospital. So they had altogether to decide if what I proposed was OK for these people or not. So I suggested three big glass cases on wheels, with shelves and a lot of these same clay things from everyday life, and they said it's probably very good for these people. So I was making them at the studio, somewhere in Holland, and then they brought everything to the hospital and I was invited to install it. That took several days. And they told me that it works well – patients would come and look, and they could recognise these things from their previous life. And I made even more complicated things – I still don't understand how I made them from pieces of clay. I made a children's tricycle at full size size, among other things. There were a lot of pieces – not as many as in the installation, but the cases were full of these. Or some old-fashioned machine for mincing meat that my mother had – and a lot of other things. I saw photographs and videos of how the patients, sometimes on a wheelchair, would come and smile seeing these things. And there was a funny thing. I lived there for several days. So they gave me the room, the same room as these guys, with all the equipment for these wheelchairs and everything. So I spent three days living in this place. There was a huge atrium where I was supposed to put my pieces and once I was really late, sitting there and thinking about the work after everyone went to sleep, and suddenly two women appeared with very strange faces, and they came very close. I could see they were really nervous and frightened – they were from the staff of the hospital. And they said: “What are you doing here?” And I said: “Just thinking.” “Why are you not in the room?” I said I just wanted to think and I had a little bottle of something with me. I didn't understand from the beginning what they meant, but they thought I was one of the patients. And it's maybe quite a dangerous situation for them because there was nobody, only two women... and a crazy person. So they were standing like this [gesturing], ready for anything! And I said I'm not one of those people. “Who are you?” they asked. I said: “I'm an artist from Russia.” And I understood that this made it even worse [laughs]. Completely mad – an artist from Russia.

MD: As if you had said I'm Napoleon, or something... [laughs]

AB: So it took me like ten minutes to prove that I am an artist from Russia, and then they relaxed a little bit.

MD: We should probably finish here. It's been great.

RA: I think that's a pretty nice ending to our conversation, thank you.

AB: Thank you.

Published 17th June, 2016. Title changed to 'Space Drawing': A Conversation with Alexander Brodsky' on 30th April, 2017. -

PR

PROLOGUE: Of ‘Things Between Things’

Piotr Lesniak & Chris French

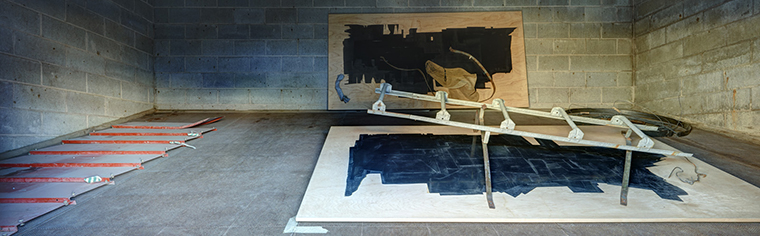

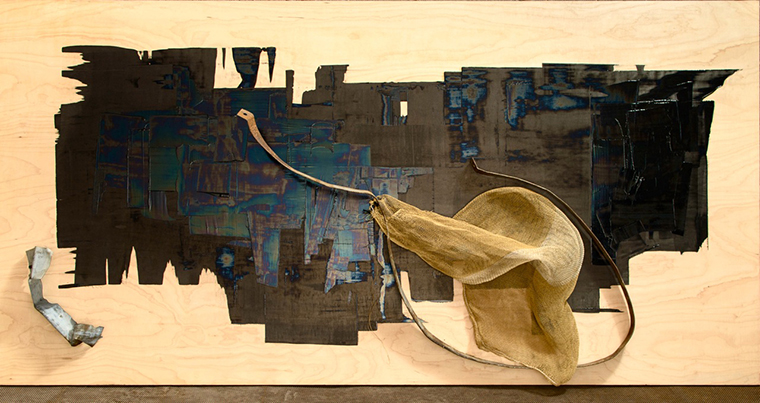

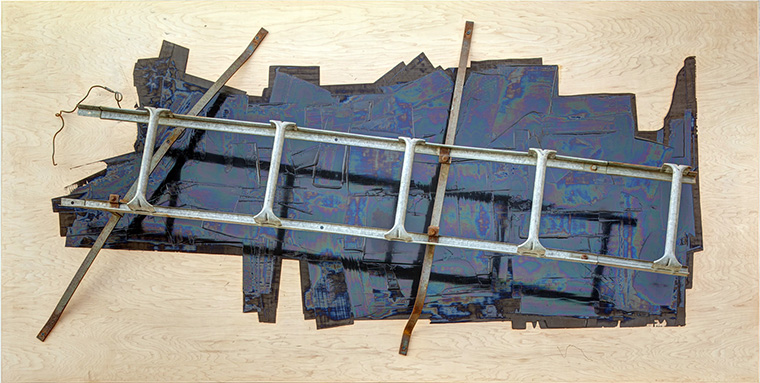

Alexander Brodsky. Facades. Triumph Gallery, Moscow, Russia, 2013.

On behalf of the Drawing On: Surface and Installation editorial team

Sebastian Aedo, Konstantinos Avramidis, Sophia Banou, Chris French, Piotr Lesniak, Maria Mitsoula, Dorian Wiszniewski

In the conversation published as a prelude to this issue of Drawing On, architect and artist Alexander Brodsky speaks of a depth of surface in his work:

“When you make etchings—this kind of mysterious technique… [it] gives you the feeling of really deep space behind the paper... [I]t is a wonderful feeling that even if you don’t like the drawing itself, it still has some space inside.”[01]

Drawings, Brodsky suggests, whether those made on the thin surface of paper or “space drawings” taking the form of installations, embody a certain kind of generosity, a feeling of depth, that goes beyond their immediate material quality or content: they make “space inside” themselves, within which we might install ourselves. They offer a space for thinking, for invoking “wonderful” feelings.

It seems appropriate to begin this, the second issue of Drawing On with such a description of generosity, not least because our previous issue, Drawing On: Presents, grew from an interest in gifts. Framed by the gestures of reciprocal gifting described in the opening lines of the poem Presents by Norman MacCaig,[02] Drawing On: Presents explored the gifts given and received in and by design research practices. In design and research this gifting and these gifts, as the prologue to our first issue posited, are of different kinds.[03] Gifting is a presenting of the Self to the Other through work, for example the presentation of a project or the staging of an exhibition. In design-research this gifting also takes the form of a presentation to the Self through the Other: the way work is presented offers the work the opportunity to act upon and remake the Self. Presentation (the drawing of a drawing, the installing of an installation) is an affective act. Following Witold Gombrowicz’s proposition, here to design is not simply to concern oneself with the shape of things, but with the shape of things between things, with one’s relationship with the world described, navigated and mediated through objects and processes of design.[04]

Although framed as an invitation to participate in a research symposium, the gestures of generous offering (and receiving) described in MacCaig’s poem, and the understanding this evokes of the particular relationship between a researcher and work, seems equally pertinent to the theme(s) of Issue 02: Surface and Installation, themes that we see as autonomous but complimentary conditions and acts (the surface, the installation, surfacing and installing. We understand surface and installation both as means of presenting work to others (the surface of a drawing, the situation of an installation) and as acts that present work to ourselves, that allow us to see the space (for thinking) made by these design acts.

It is in the materiality of the surface, Brodsky suggests, and the materiality of surfaces in installation that we may begin to notice what is offered, to see a space for wonderful feeling. This space, offered by a surface, by the working of a surface, by engaging with the very material of a surface, opens up the chance (choice perhaps) to forgo the uncritical, contemplative (in Benjamin’s sense)[05] approach to the work of architecture, art, or scholarship, and instead to re-think what ‘quality’ might mean, what we think might constitute ‘good’ design. The space of the surface fosters criticality.

In the call for submissions for this issue of Drawing On we sought to emphasise the significance of matter, of making-material as a key step in developing such a criticality, in moving from critical enquiry (a question) to critical methodology (a way to question, of questioning). Installing, drawing, presenting, indeed any process, however temporary, where ideas are physically drawn out (made in material, made (to) matter) is both a register in itself of situation, and a situation that might in turn be registered, recorded, represented. Surfacing and installing thus offer ways to question, to develop ways of questioning, through making material. This is made possible because by way of design, unlike by way of the algorithm or rationalism, matter (the material of a surface or installation, but also that which matters in surfacing or installing) can extend beyond any initial programme, intention or expectation placed upon it; enabled by the spaces for thinking made by design, matter can transgress situations, states, forms. Surfaces and installations, we wrote by way of a call for submissions, “record relationships within and beyond their own limit: upon, beneath or above their own surfaces, between situations. Therefore, drawing on surfaces and installations, we open questions of how to draw out the worlds of and between here and there.”[06] Surfaces and installations questions those things between things.

The work of Alexander Brodsky makes the methodological status of surface and installation evident. From the prints made with Ilya Utkin in the years of “paper architecture,” to the more recent installations at the Cultural Centre in Vienna or Pittsburgh, surfaces are more than surfaces, installations more than the re-presentation of complete works. Surface is at once the means for receiving and a vehicle for offering new depths. Installation is not merely a space filled with spectacular works, but a situation of engagement with the matter(s) at hand, in which a layered intersubjectivity paves the way for ‘re-making’ oneself. Both open up unexpected conditions of spatiality, an eloquent depth that is beyond the reach of metrics, of metricity.

It is in this sense, through the coupling of complementary acts of making space—drawing on surfaces and making installations—that the current issue seeks to nourish a discussion of critical design research methodologies. Encouraged by the works of our contributors, the insights of the reviewers and critics, and the discussion of Alexander Brodsky’s design oeuvre, we are pleased to present to you the second issue of Drawing On: Surface and Installation.

Published 12th March, 2018.

Notes

[01]^ See A. Brodsky, M. Dorrian, and R. Anderson. 2017. ‘Space Drawing: A Conversation with Alexander Brodsky’, in Drawing On, Issue 02: Surface and Installation, available at: drawingon.org/issue/02 (accessed 10th March, 2018).

[02]^ “I give you an emptiness, I give you a plenitude, Unwrap them carefully. One’s as fragile as the other.”

N. MacCaig. 1974. ‘Presents’ in MacCaig, Norman. 1993. Collected Poems. London: Chatto & Windus, p.316. See also D. Wiszniewski. 2015. ‘Prologue: Drawing On Plenitude and Emptiness’, in Drawing On, Issue 01: Presents, available at: drawingon.org/issue/01 (accessed 10th March, 2018).

[03]^ See D. Wiszniewski. 2015. ‘Prologue: Drawing On Plenitude and Emptiness’, in Drawing On, Issue 01: Presents, available at: drawingon.org/issue/01 (accessed 10th March, 2018).

[04]^ Gombrowicz paraphrased, see Goddard, Michael. 2010. Gombrowicz, Polish Modernism and The Subversion of Form. Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press, p. 32.

[05]^ See Walter Benjamin and Michael W. Jennings, “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility [First Version],” Grey Room, 39 (2010), pp.33–34. Thesis 18.

[06]^ See ‘Call for Submissions: Surface and Installation’, in Drawing On, Issue 02: Surface and Installation, available at drawingon.org/issue/02 (accessed 10th March, 2018). -

01

Exhibitionist Drawing Machines

Timothy Burke

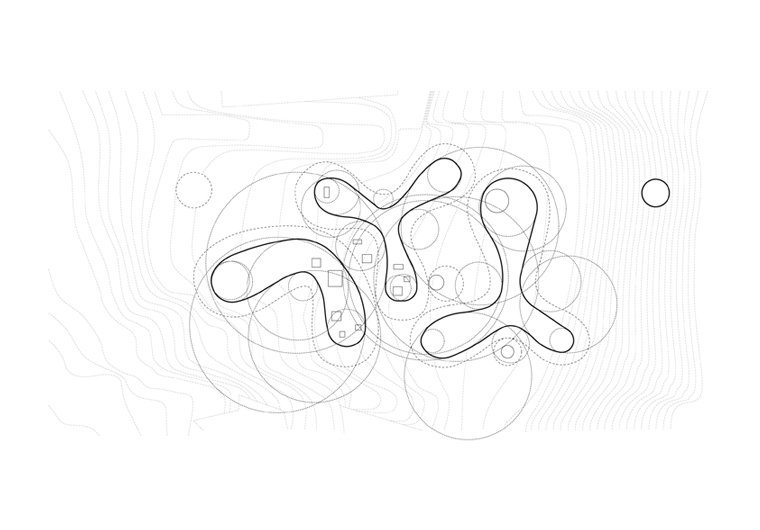

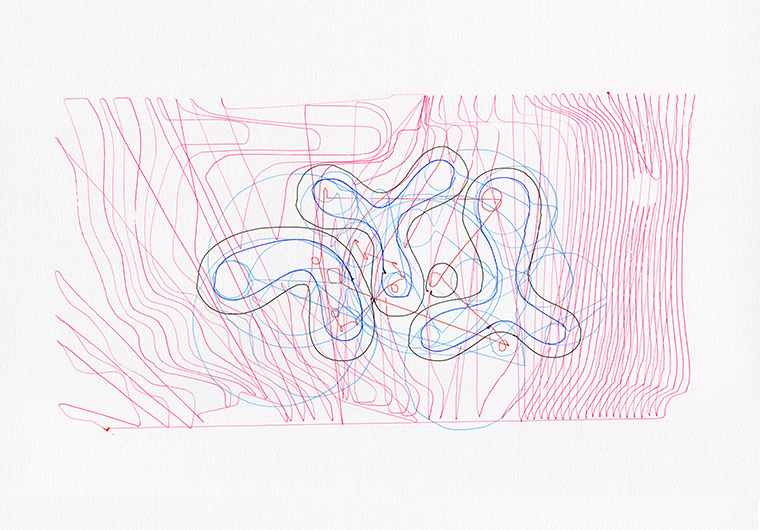

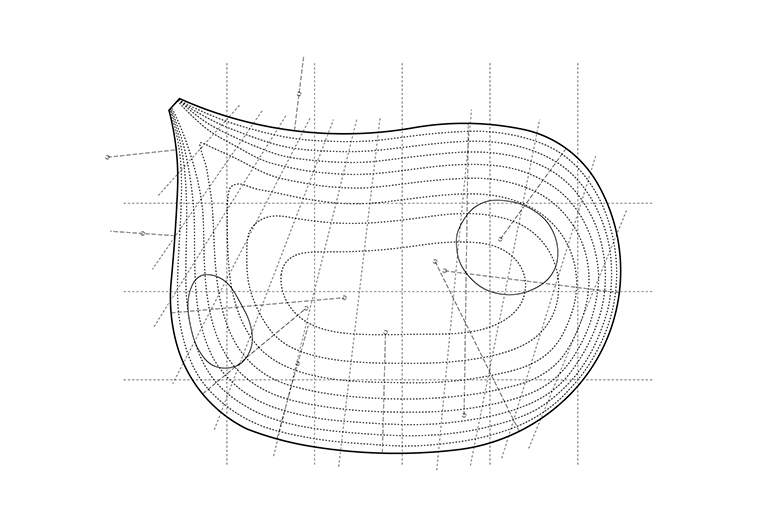

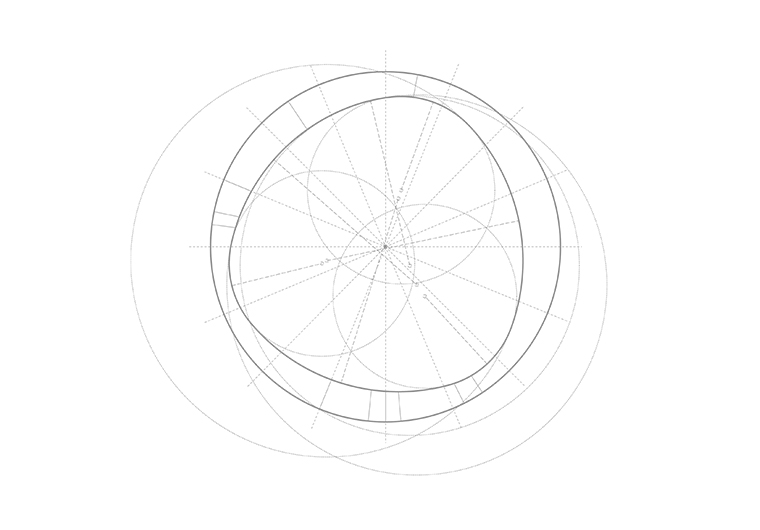

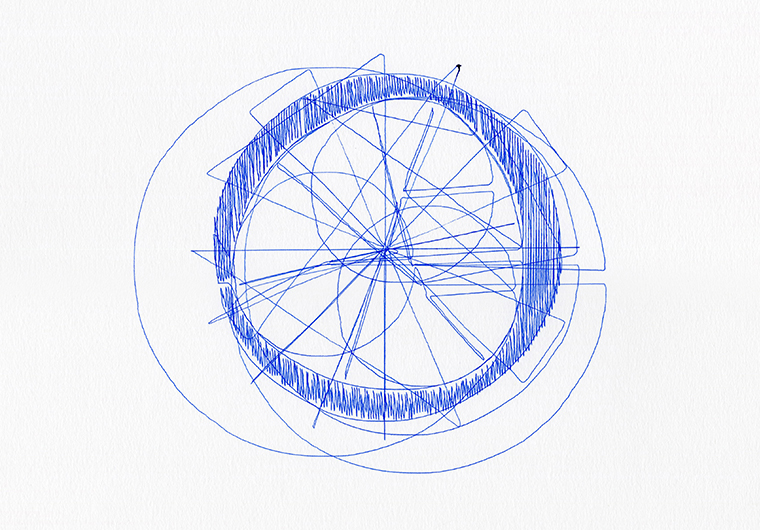

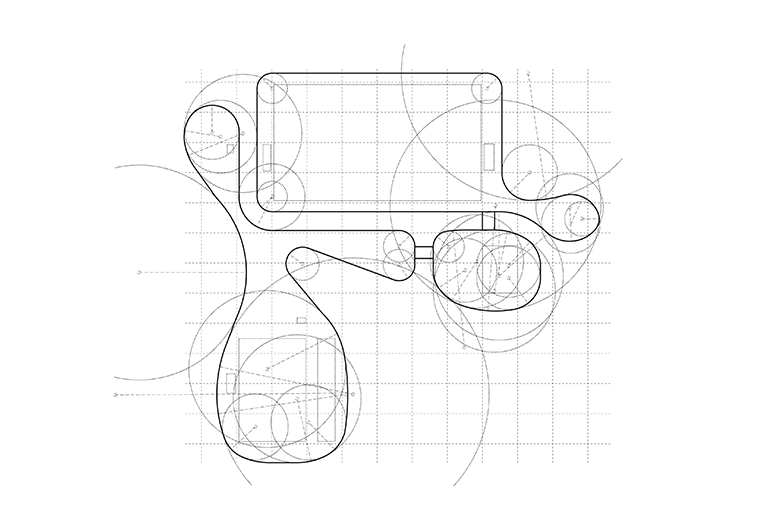

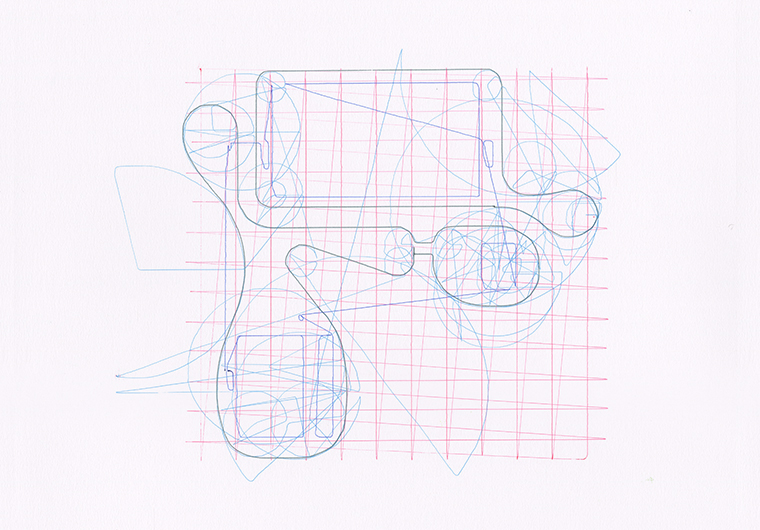

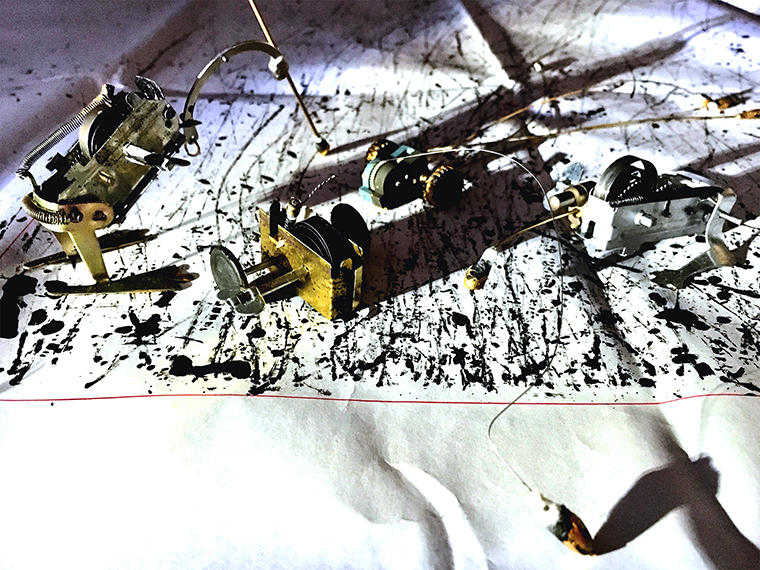

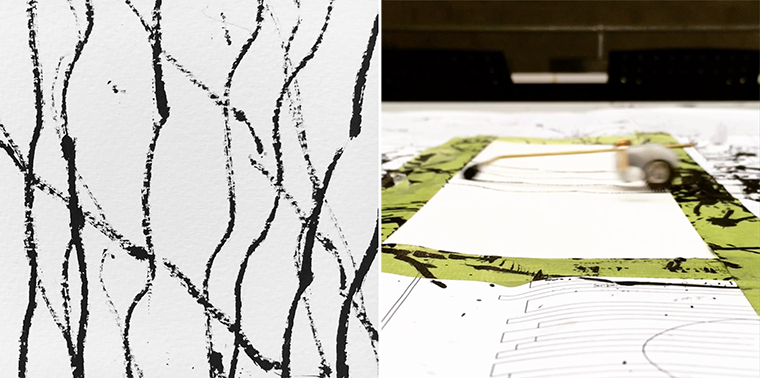

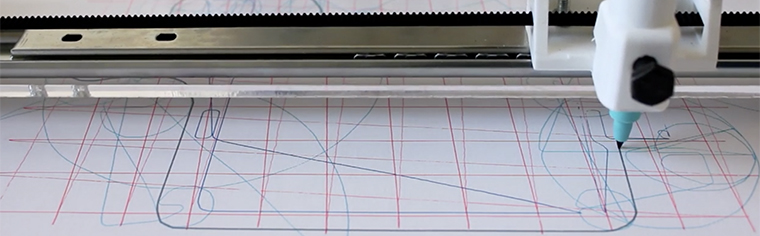

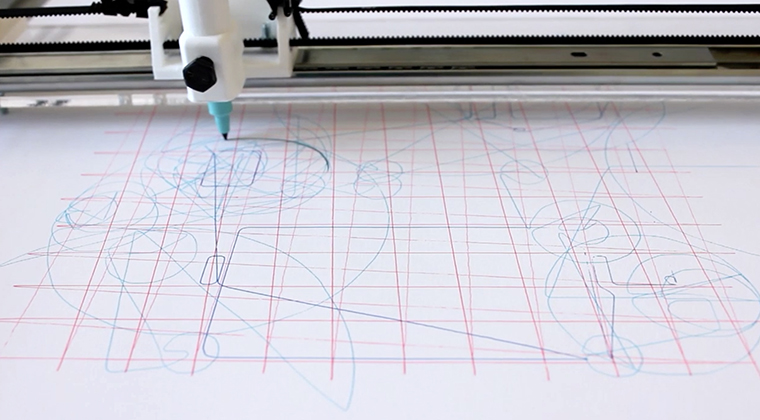

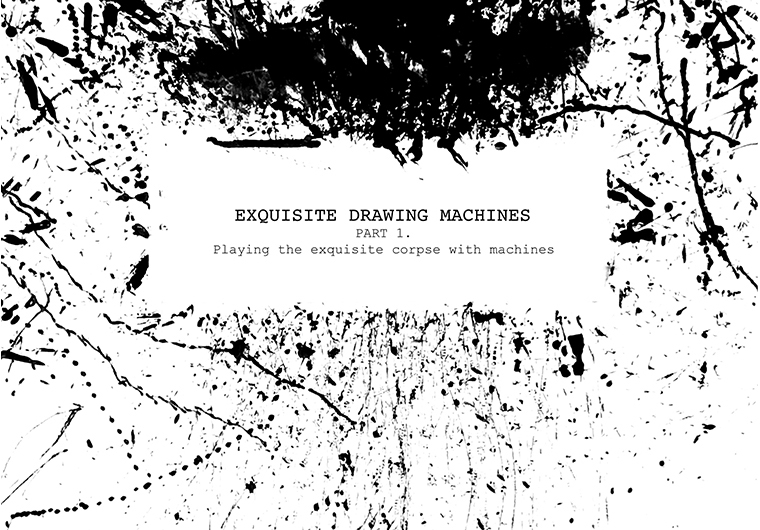

Playing the exquisite corpse with machines. Drawing by Timothy Burke.

“The essential discovery of surrealism is that, without preconceived intention, the pen that flows in order to write and the pencil that runs in order to draw spin an infinitely precious substance which, even if not always possessing an exchange value, none the less appears charged with all the emotional intensity stored up within the poet or painter at any given moment.”[01]

André Breton, 1972

In Paris, in July 1959, Marcel Duchamp, Tristan Tzara, Man Ray, Roberto Matta, Hans Arp and a swathe of by-then marginalised surrealists witnessed a marvel: Jean Tinguely’s thirty-three Méta-Matic drawing machines which, over the course of the ‘Méta-Matics’ exhibition at the Galerie Iris Clert, produced over 1000 hectares of works of art. Not only was this, as Tristan Tzara announced,[02] the ultimate victory of Dada but it was also the total mechanisation of the psychographic methods of automatism (automatic writing and drawing) that Breton had developed to kick-start Surrealism four decades earlier.[03] In Surrealism and Painting (1928), Breton suggested that automatism could be achieved not only by “mechanical means”[04] but also through the mechanisation of “the pen that flows in order to write and the pencil that runs in order to draw.” In the view of the surrealists, this had now been realised in the expansive oeuvre of Méta-Matics (produced between 1955–1959).

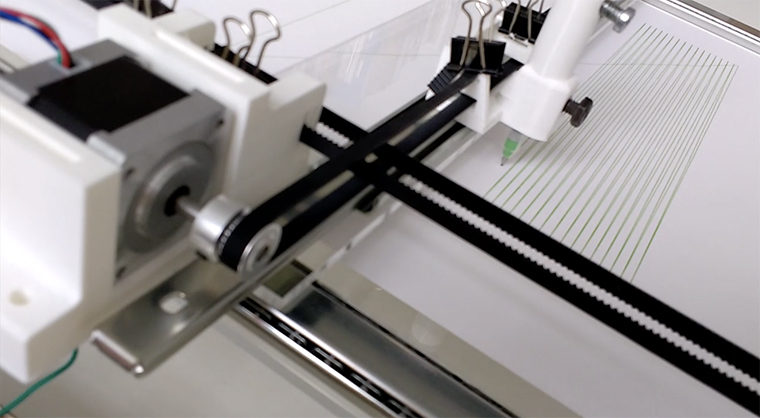

Of course, “the pen that flows” had already been found (and fetishised) by the surrealists in the antiquated, pre-industrial machines of the eighteenth century: the automaton—the original drawing machine. Pierre Jaquet-Droz’s Young Writer, was perhaps one of the most advanced and famous of the automatons and became a touch-stone for surrealism, not just for its marvellous, uncanny and mystical implications, but as a materialisation of machinic automatism.[05] This writing machine—a clockwork doll capable of writing with quill and ink—extended beyond its function of writing to become an icon for an arcane form of mechanisation. In this, and other automatons, a rationalist-mystic dialectic converges, as in Tinguely’s drawing machines. This dialectic challenges purely functionalist views of the machine. What separates Tinguely’s Méta-Matics from the automatons is that they were irrational machines; with messy and imperfect lines these Méta-Matics simultaneously mocked the technologies of mass production and mimicked them.[06] These machines—and the historic lineage of drawing machines that followed—function as both works of art and the authors of art.[07] They lay bare their means of production; they are exhibitionists.

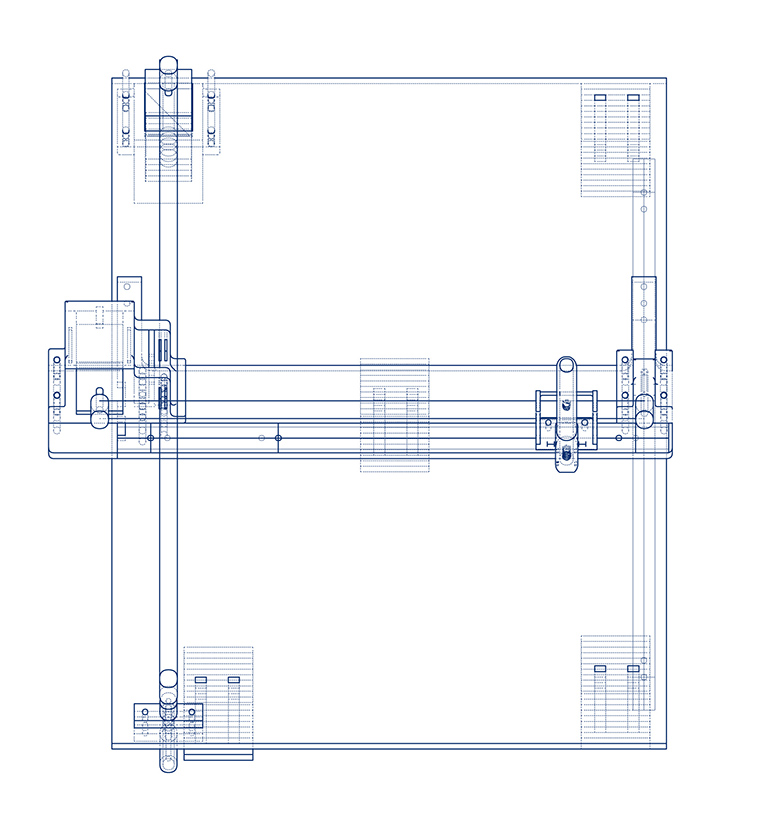

Through these machines, the work of art comes to exist on two planes: the plane of the surface and of the installation. It is this quality—this duality of the exhibitionist machine and its works—that the design-led research project entitled Exquisite Drawing Machines explores.[08] This project frames the exquisite drawing machines as both automatons and instruments of automatism. They are never, though, truly autonomous: as I will discuss they are co-conspirators and co-authors that are engaged in a choreography of drawing, reading and play.[09] Seen beyond the dualism of mysticism and rationalism, the ambiguity of the machine as both “self-developing” and “externally designed” that Donna Haraway identified in her cyborg manifesto (1984) offers opportunities for design thinking, and begins to take shape in what Jeffery Kipnis once described as “forms of irrationality.”[10] I am drawn to these paradoxes of conflicting dialectics, incongruences, dualisms verses hybrids: a plurality of definitions of architecture that are indeterminate and expansive. The Exquisite Drawing Machines posit the question: can machines be the play-things that open up the realm of the marvellous (as the surrealists once recognised), how do we engage with the shared role taken in drawing with (both as pen and as partner) automatons, and how do we distinguish the boundaries of authorship as technology makes them increasingly indistinguishable? Again, as Haraway enigmatically announced, “[w]e are responsible for boundaries; we are they.”[11] The complete dissolution of these boundaries (of producer and means of production, of operator and operated) allow machines, as a generating concept, to embody new approaches to thinking about architecture.

Exquisite Drawing Machines MK.1 (the band shot). Photograph by Timothy Burke.

Part 1. Playing the exquisite corpse with machines

To play the drawing game of the exquisite corpse (a.k.a. ‘rotating corpse’, or ’heads, body, and legs’) a piece of paper is folded evenly into segments and passed between players, in turn each player draws a part of a figure in the visible segment of the paper, before folding the paper over and passing on the paper. The next player, oblivious to what was drawn before and what will be drawn next, fills in the subsequent segment, and so on. At the end of the game the page is unfolded to reveal an image with often surprising results. Originally created as a word game, it was one of the many parlour games developed by the surrealists. Among the many purposes of the game, it negates traditional conventions of authorship, enabled conditions of chance, and of course is a form of entertainment.

To play a game of the exquisite corpse with machines is simple: replace each author with a small drawing toy. The purpose of an exquisite drawing machine is to be a unique author. Each machine is designed to be different from the next, both in the way that they are constructed and the way that they draw. The drawing machines are assembled from found objects—a collection of ‘readymades’ of mechanical bits and pieces.[13] At the core of each drawing machine is a spring-wound toy which has been deconstructed to reveal its inner-workings. Usually this involves removing the outer case of the toy—often something resembling an animal, vehicle or human figure—and all other components of the toy not essential to the functioning of the inner mechanism. Once stripped bare, the function of the machine, movement, is augmented by adding to the mechanical mechanism other deconstructed machine parts: old film cameras, lights, slide projectors and musical instruments. Finally, a cotton tipped prosthetic stylus for dipping in ink is attached to the chassis to allows the instrument to draw. This method of making—what I would describe as bricolage or tinkering—produces a kind of arcane proto-technological drawing creature, or an antiquated machine.

These machines play the exquisite corpse; they are put to play. The Exquisite Drawing Machines are built to be unpredictable, to self-generate and to move in unknowable ways. What is drawn cannot be pre-determined. Even the extent of indeterminacy built into each machine is unknowable until the game is played, until the machines reveal themselves as drawing agents (although with each new machine I am more successful in making them operate unpredictably). This indeterminate playing with and through machines begins to reveal a method of disrupting the relationship between author and drawing. The author surrenders control of the drawing process by making a machine to draw and to be unpredictable; the machine replaces the author as the principle agent of the drawing and produces a drawing that is unknowable. At the very least, by relinquishing control of the line making the author brings uncertainty to the drawing; at the very most the machines behave seemingly at will, and can suddenly change the direction of the drawing. I recorded this observation when I first played the game with MK.3-01 (Fyn), writing:

What a naughty machine. Does it have stage fright? It wobbles and twists as if repelled by the page. When it finally does cross the threshold of the page’s edge it bounces over the surface; not a mark was made! This goes on and on until a picture is slowly drawn: one that shows its discontent for preforming on its page. Yet despite this there are some of the most beautiful, spiraling lines, dashed off the margins. This machine had bigger dreams.

These new mechanical authors generate drawings that are unexpected and draw from conditions of chance. However, while the machine-author distances the human-author from the drawing, the wind-up mechanism undermines any illusion that the human hand is totally removed from the drawing procedure. For the drawing to come into being someone has to wind the machine, load it with ink and release it across the page. Although this person isn't forming the line themselves, their proximity to the process allows them to be immersed in the drawing process. While this is unlike the immediacy of drawing a line by hand, a different kind of experience is formed through the spectacle of the machines in action. There is a profound curiosity to watch the machines as they come to life and play.

Exquisite Irrationality: Play As Design Research

It is not only the machines that mediate the role of the author in the drawing process, the structure of the exquisite corpse game itself is a critical device hinged on a critique of mechanisation. Hal Foster makes this observation in his Compulsive Beauty thesis, recognising the game as a parody of the distribution of labour. While he discusses the game within the structure of surrealist automatism—as a device that de-centres the rationalisation of the modern world that represses primal desires and fantasies—he suggests that these exquisite corpses “mock the rationalised order of mass production;” that they are “critical perversions of the assembly line.”[14] Foster observes the same mechanisation of the human body in Jaquet-Droz’s automaton, and we can see the same mockery of technical reproduction in Tinguely’s “do it yourself” Méta-Matics. However, unlike Tinguely’s machines which are powered by motors and fed by long rolls of paper,[15] the Exquisite Drawing Machines challenge the idea of manual labour through the slow, repeated winding of the mechanism. The spring stores and converts the energy from the hand into the making of the drawing. This process is slow and drawings can take over an hour to emerge.

It is not only the perversion of mechanisation that interests me however, but how play may be used as a critical research strategy. The ethic of playfulness and indeterminacy establishes a position that doesn't take itself too seriously: it becomes a way to be open and engaging rather than closed-off and defensive.[16] Such conflict exists in the doctrines of La Révolution Surréaliste, between disruptive and playful modes of criticality. I am interested in the playfulness of the exquisite corpse as a method to challenge rationality with a healthy dose of irrationality. As Breton observes, “with the exquisite corpse we had at our command an infallible way of holding the critical intellect in abeyance and of fully liberating the mind’s metaphorical activity.”[17] So just what is being held in abeyance?

What the Exquisite Drawing Machines provide are artefacts that can be studied to reveal the pre-occupations of their author, while the drawing itself operates outside of the author’s control. Bearing in mind that collaborative play is a multi-authored event, by identifying where the controls and rules that the author places on the experiment end we can observe what is being held in check. For instance, observe the strictness in the way the exquisite machines are made: there is a controlled palette of materials such as brass and steel, deliberately chosen mechanical parts from old machines, a uniform cotton nib on each machine to apply black ink in a predetermined effort to preserve the primacy of the line by negating different drawing mediums and colours. Now observe what is outside of the author’s control: sometimes dense, sometimes light ink splatters, long swooping lines, uncontrolled seams of dashes and dots. Tinguely's machines too have their own consistency of black-painted constructivist geometries, planes, and rods which are also unlike the scribbles they produce. This relinquishing of control, the randomness of what is produced, is in contrast with the inescapable pre-occupation of the authors own aesthetic entanglements. This is a rational order held in abeyance.

This exploration of the rational and irrational through play is intended to be suggestive of a broader questioning of some of the orthodoxies of architecture and technology. Here, play is the petri-dish for this exploration. Play, as Benjamin describes, is the imitation of the outer world in the imagined inner world of the child.[18] Drawn to the detritus of the construction and destruction of worldly things (such as the building site), Benjamin writes that children play with these things in such a way that they “do not so much imitate the works of adults as [they] bring together, in the artefact produced in play, materials of widely differing kinds in a new, intuitive relationship. Children thus produce their own small world of things within the greater one.”[19] Just as the exquisite corpse simulates the production line, drawing machines imitate authors, somehow appearing self-conscious. This may be in some part driven by the randomness of their actions—as they suddenly shift direction just as they reach the edge of the page—or perhaps it is their anthropomorphic characteristics as they hop, limp and scramble across the page invoking Benjamin’s “small world” of play. While their drawings themselves compress these moments to the surface of the page, the interaction of the Exquisite Drawing Machines during play is expansive. I’ve come to realise that this is where their instrumentality resides.

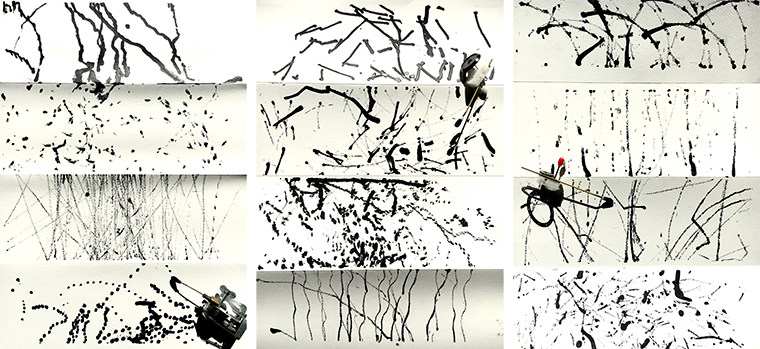

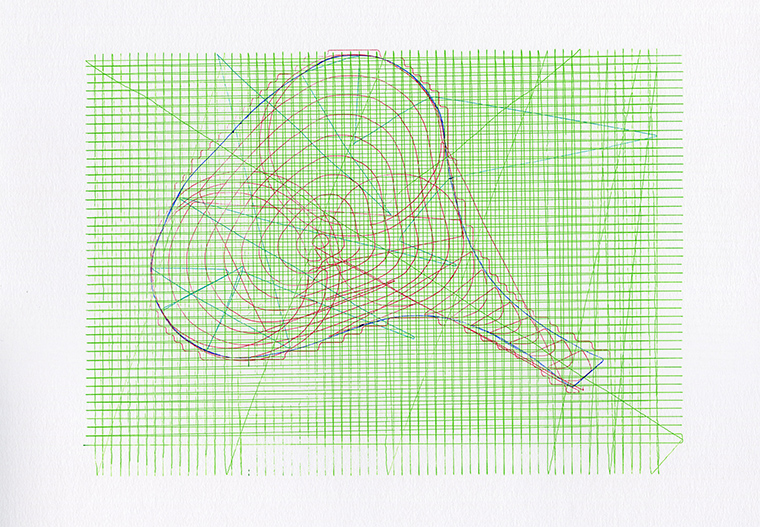

Playing the exquisite corpse with machines, this “new intuitive relationship” invariably manifests through an autopoiesis quite unlike the hand. The Exquisite Drawing Machines recompose a new visual language of geometries and fields with lines, dots and dashes,[20] but also lead to a method of drawing that is emergent rather than prescribed; open rather than closed; indeterminate rather than pre-determined; undirected rather than directed. These drawings emerge from “the undirected play of thought” that Breton champions,[21] and are akin to Jacques Derrida’s notion of “free play.”[22] As analogue machines, they cannot be coded to perform specific computations. These machines are unpredictable. They misbehave. In this way, they are indeterminate and disruptive agents of drawing.

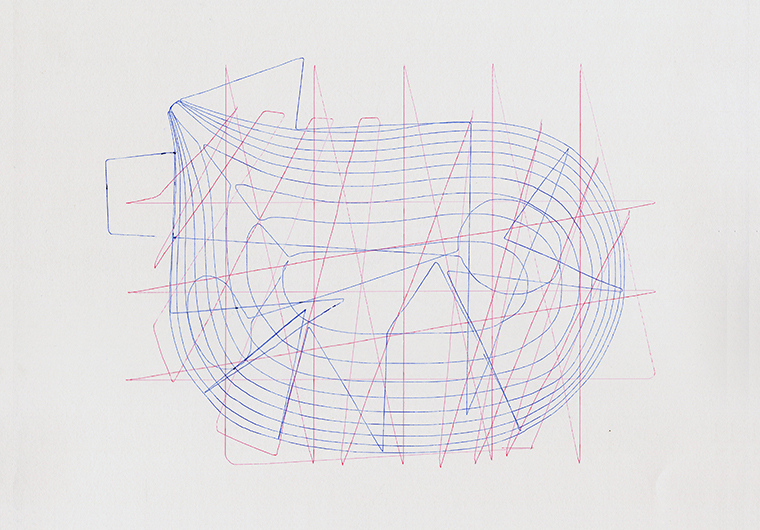

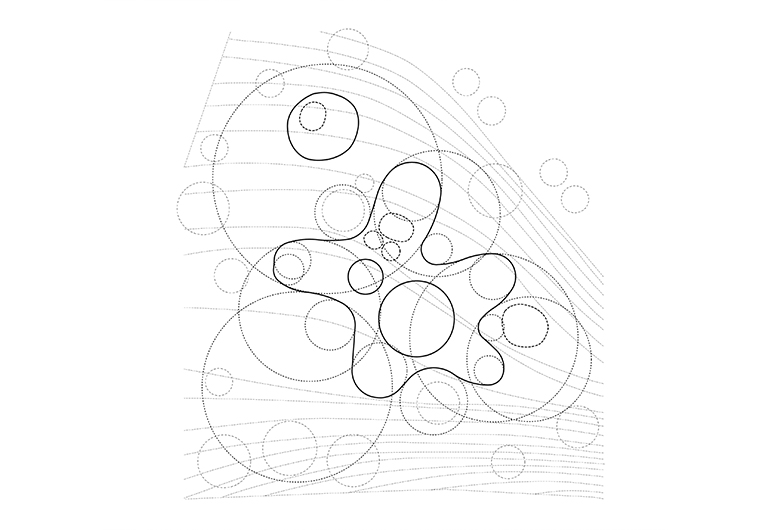

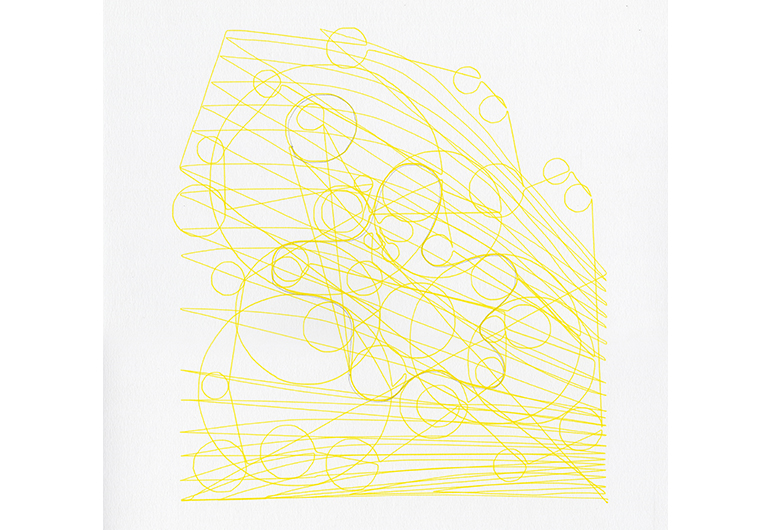

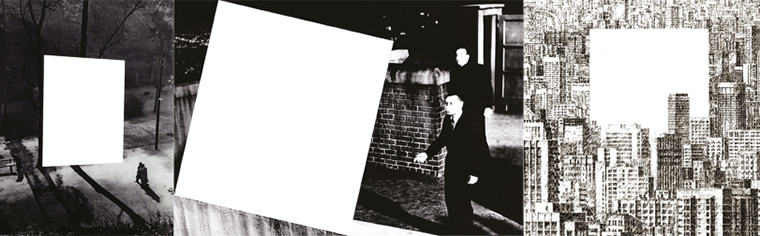

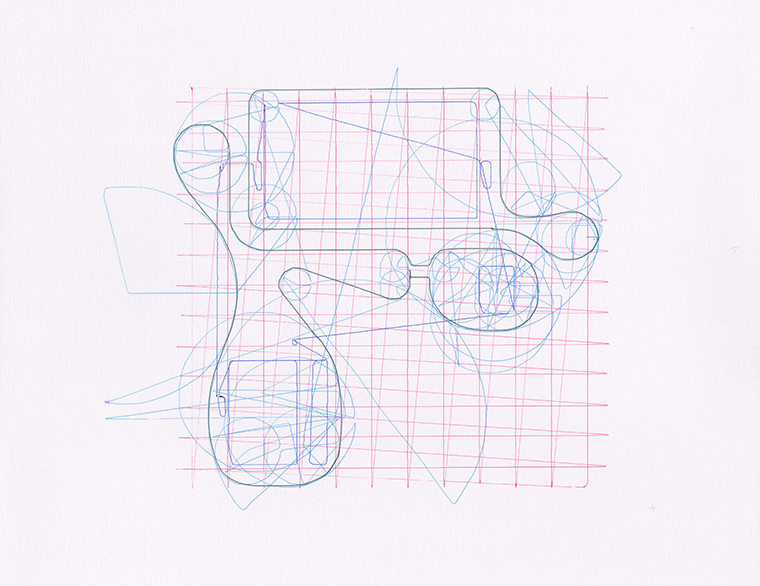

Three games of the exquisite corpse by three series of Exquisite Drawing Machines (MK. 1, MK.2, & MK.3).

Three games of the exquisite corpse by three series of Exquisite Drawing Machines (MK. 1, MK.2, & MK.3).

Drawings by Timothy Burke.

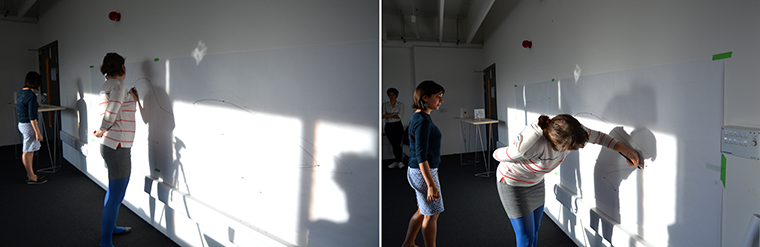

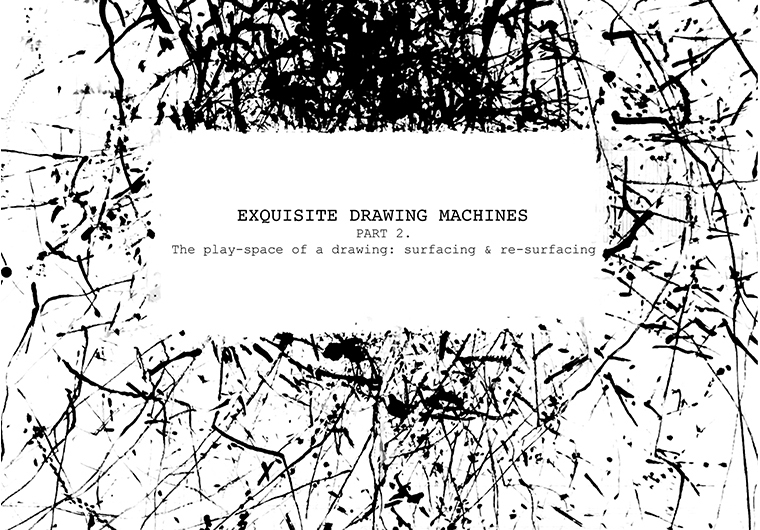

Part 2 – The play-space of a drawing: surfacing and re-surfacing

The way the Exquisite Drawing Machines behave as they operate—perhaps inscribed by their former lives as toys—is sometimes anamorphic, usually hilarious and occasionally naughty. As machines of indeterminacy they fail often and spectacularly, leaving traces of these events as pigment on the surface of the page. The spectacle of what happens beyond the surface of the page is what I have come to call the ‘play-space’. The play-space of a drawing is experiential, emergent and fully absorbed into the production of drawing.

During Tinguely’s Méta-Matic exhibition in Paris, his thirty-three machines operated more like performance art, where the patrons of the exhibit were implicated not only in the making of the drawings but in the whole spectacle of the event. Here, the drawings as works of art are only as valuable as the process of their materialisation. The Exquisite Drawing Machines are bound to the same fate. The way the play-space is shared, recorded and recounted is significant in order to provide meaning to the drawing. Without the knowledge that the drawing was produced by drawing machines it may simply be read as a composition of lines in black and white, whereas each line is an inscription of its materialisation: the conditions in which it came to be. This materialisation emerges in characteristically different ways. I recognise these as three stages of surfacing. These are illuminations where the nature of the object (the machine), the space of play, or the surface of the drawing is somehow revealed during the event of play.

i. The Character of the Object (a Self Portrait of a Drawing Machine)

One of the more marvellous and unexpected moments emerged when creating one of the corpse drawings. It was the first mark made by MK.2-04 (Happy Feet), the fourth of the second series of drawing machines. At the time it was created I recorded the event in my journal:

A floret. A clock. Radial lines are drawn from a fin as the fulcrum of its round belly casts a large black mask over the perfect polar arrays. Soon only peeks of this remain. The game stops when the penguin’s feet get stuck together.

This drawing was made in a pre-cursory game of the exquisite corpse. Before each drawing machine is made, the game is played with the toy as it had been acquired. The toy, in its original state, rolls across the page in the same method as Yves Klein’s Large Blue Anthropometry (ANT 105). Here pigment is applied to the page directly from the surface of the body as it moves around the page. This process allows something akin to what Benjamin discusses on the subject of Dada automatism, readymades, collage and photomontage: “the tiniest fragment of daily life says more than painting. Just as the bloody fingerprint of a murderer on the page on the book says more than the text.”[23] This is the first stage of surfacing. The toy, as a ready-made, imparts a new drawing in the world that has been previously unseen. In that moment, completely unexpectedly, it told me more about the nature of geometry than I had considered possible of a small, plastic penguin.

%20%5B760px%5D.jpg) MK.2-04 in its original toy state rolls across the page like Yves Klein’s Large Blue Anthropometry (ANT 105).

MK.2-04 in its original toy state rolls across the page like Yves Klein’s Large Blue Anthropometry (ANT 105).

Drawings by Timothy Burke.

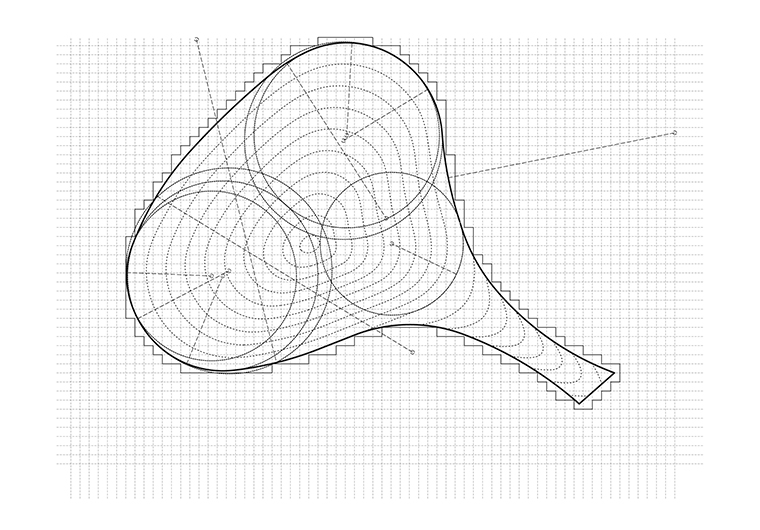

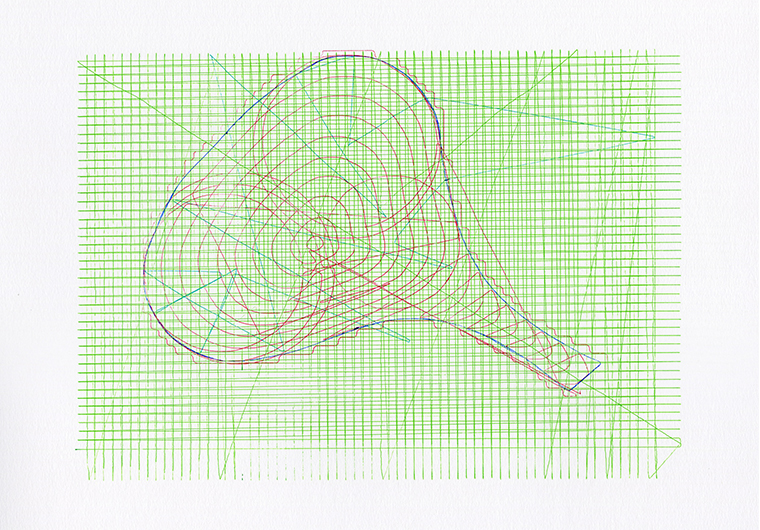

ii. The Character of Space (Spatial Instruments)

The game is played again after the drawing machines have been re-functioned from the toy and no longer draw with the surface of their body but with a prosthetic stylus. They now make intentional lines that can be read easily to describe the event of play. Every line they cast is unique but distinguishable. There are fifteen drawing machines that draw with lines, dots, and dashes that can be wobbly or concentric, slow and careful or quick and erratic. However, every line is affected by the physicality of their making—the amount of ink they carry, how much the spring has been wound, the texture of the page, the flatness of the surface, the drag of the air—which inevitably leads to them falling over, hurdling off the page or breaking down, waiting to be repaired again. The way these unique lines are cast is the second stage of surfacing: where the nature of the machines’ (mischievous) character and the nature of the spaces they draw within begin to overlap.

This second stage of surfacing is the materialisation of an event. It describes the play-space of the drawing (as an action). Of course, in action-painting, the same has been said about Jackson’s Pollock’s studio, where large canvases are worked on the floor of the small room. The painting records the physical and mental space of the artist and the artwork. Although not ‘architecture’ in themselves, I am interested in how we can read these as architectural drawings.[24] This is not so much to do with a drawing that describes architecture or pictorial space but one that emerges from it. The Exquisite Drawing Machines attempt to explore this. They are not just drawing-machines, but architectural ones. Unlike Tinguely’s Méta-Matics which are large installation works, the Exquisite Drawing Machines are small and deployable. They are instrumented by space, where spatial parameters inform outputs and, as deployable devices and instruments of space, they operate across multiple sites.

MK.2-04b drawing in its refunctioned state. Drawings by Timothy Burke.

MK.2-04b drawing in its refunctioned state. Drawings by Timothy Burke.

iii. The Character of the Surface (The Fold and the Margin)

Within the structure of the exquisite corpse game, it is important to recognise the technique of folding as the primary disruptive strategy of automatism. It serves two functions: (i) to provide a method for allowing a multi-authored drawing by demarcating a physical boundary to each author, and (ii) to hide the other parts of the drawing from entering the authors’ consciousness. What this in effect does is divide the surface of the drawing into two states: the hidden state of the drawing (as a verb) when it is folded, and the revealed state of the drawing (as a noun) when the page is unfolded. This transformation is separated by time, allowing the illumination that comes out of the drawing to occur later than the drawing itself. This causes a latency between the act of drawing and what surfaces; more profound illuminations are delayed until the page is unfolded to reveal the figure that has been made up from each segment. It is therefore a delay that separates the drawing (writing) from the exhibition (reading) of the drawing.[25] This is the third stage of surfacing, or more precisely, re-surfacing.

However, the unfolding of the page is not the only resurfacing that has come out of this research. Through continued play unexpected drawings have emerged beyond the confines of the game, where disruptions to the paper’s surface and the delineation between each machine’s territory produce entirely different drawings. It is in the margins—on the large sheet under the folded page that was intended simply to stop ink going everywhere—that unplanned drawings tell the complete story of the goings-on of the game. It is in these ‘marginal’ drawings that the primacy of individual lines is subsumed into a cloud-like mass. This marginal drawing exists outside the confines of the author’s intention, where composition and consequence were not considered. It is where most of the mishaps happen. This is where occasional ‘cheating’ occurs and where the machines are interrupted by the helping hand of their user. What this drawing does show is the relationship between the author, the surface of the work (which masks a blank section in the page), and the actions of the drawing machines. While the exquisite corpse records the conscious decisions of the person playing the game, the marginal drawing occurs outside of this consciousness. It is, therefore, perhaps a better example of automatism than the exquisite corpses themselves.

Playing in the margins. Drawing by Timothy Burke.

Playing in the margins. Drawing by Timothy Burke.